Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Saturday, 3 January 2026 00:06 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The current state of agriculture in Sri Lanka serves as an important catalyst to climate disasters

Nature seems to be at war with a market-driven investment pattern slowly decaying the means of survival for the masses. In many ways, this ecological pushback expressed through Cyclone Ditwah, mirrors the 2022 people’s uprising, which sought to overthrow an entrenched political establishment. Just as that quest remains incomplete, nature is waging its own campaign against an economy dictated by self-interest. As the climate breaks, more decisive acts of defiance from the natural world appear inevitable, mirroring the political and economic struggles that lie ahead for the masses.

Nature seems to be at war with a market-driven investment pattern slowly decaying the means of survival for the masses. In many ways, this ecological pushback expressed through Cyclone Ditwah, mirrors the 2022 people’s uprising, which sought to overthrow an entrenched political establishment. Just as that quest remains incomplete, nature is waging its own campaign against an economy dictated by self-interest. As the climate breaks, more decisive acts of defiance from the natural world appear inevitable, mirroring the political and economic struggles that lie ahead for the masses.

The scale of devastation to crops

The immediate scale of this conflict is now finally clear. Initial estimates from the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO UN) following the Cyclone Ditwah, combined with ongoing monsoon rains, paint a harrowing picture. Over 1,200 landslides have been triggered in the hills while severe flooding in the low-lying areas affecting over 10% of the total population.

The National Building Research Organisation reports that 30% of Sri Lanka’s total land mass -home for 34% of the population- is under the risk of landslides. Flood waters have submerged 20% of the total land mass of the country, destroying roughly 380,000 acres of cultivated land. Out of this, 330,000 acres were paddy lands accounting for 86% of the destruction (FAO UN). Depending on the degree of destruction the machine rents may also rise in the absence of state intervention to restore the supply. International Food Policy Research Institute finds that 32.8% of households experience moderate to severe food insecurity while this figure is as high as 54.5% in the estates by November 2025, even before the cyclone’s devastation. Given that agricultural losses directly threaten food availability, inflation, employment and livelihood of millions, Government must prioritise the recovery and restructure of the affected agricultural land and industrial employment creation.

The trap of agricultural overextension

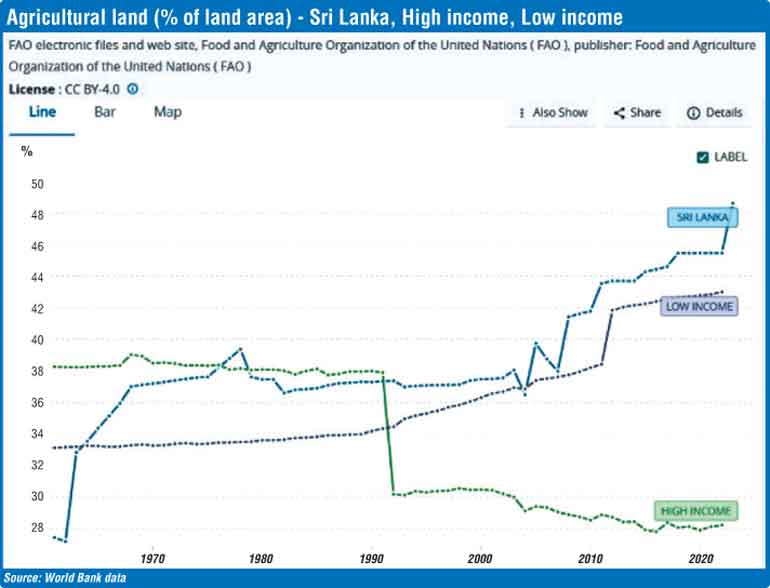

The current state of agriculture in Sri Lanka serves as an important catalyst to climate disasters. The graph below shows the extreme over-extension of agricultural land use in Sri Lanka, particularly since 2004. According to World Bank data, land under agriculture in Sri Lanka has surged from nearly 36% in 2004 to over 48% by 2023, which is significantly higher than the average for low and middle-income countries. This is further reflected by total paddy lands under cultivation increasing to over 700,000 hectares in 2024/25 Maha season from nearly 500,000 in 2004 (Department of Census and Statistics data). It is also important to note that agricultural land only constitutes 29% of the total in high income economies which has been on the decline over the years, indicating that developed capitalist centres have moved away from extensively exploiting the land compared to the periphery. This highlights mainly a dual problem: first, agricultural overextension increases the severity and vulnerability of average Sri Lankans to climate disasters. Secondly, a serious lack of qualitatively acceptable employment in the non-agricultural sector, is forcing people more and more to retreat into land-based incomes despite its many dangers and threats as the only means of survival, which in turn accelerates environmental destruction. This overreliance on land, ironically, has now become a serious threat to long-term survival.

By adopting Direct Seeded Rice (DSR) using small-scale machinery, which drills seeds directly into the soil rather than using traditional broadcasting or transplanting, farmers have reduced the water consumption by 15% to 20%, reduce methane emissions, and simultaneously freeing labour from the cultivation process. The Punjab government, for instance, actively plans to expand this technique to cover 700,000 acres across the state. Furthermore, paddy farmers in India use small-scale weeding machines instead of weedicides, made possible by the DSR method

Source: World Bank data

Sri Lanka urgently needs to uncover ways of reducing its landmass and workforce under agriculture, without stoking inflation, a drop in food availability and foreign reserves, while at the same time generating qualitatively acceptable employment outside agriculture. If we fail to do so, the requirement for emergency assistance and reconstruction due to climate disasters will become a permanent feature, given the high possibility of such future disasters.

Restructuring of Sri Lanka’s paddy economy is a significant priority in addressing environmental destruction and economic development. Given that over 86% of the cyclone-related damage to cultivated land is concentrated within paddy sector, the Government must establish ways of restructuring the paddy economy within the parameters set above.

The need to raise national savings through state control

It is critical to keep in mind the vulnerability of the external sector. Despite the sharp increase in labour remittances and moderate rise in exports, foreign reserves declined particularly in November 2025 to $6,090 million. This compromise makes a large-scale agricultural and industrial transformation difficult, without increasing national savings through restricting luxury imports, particularly personal vehicles, and reducing the foreign debt burden through creditor renegotiation, a strategy advocated by a group of 121 eminent economists, including Joseph Stiglitz, Jayati Gosh and Thomas Piketty. Rather than relying on luxury import taxes that deplete reserves to generate revenue, these savings should be channelled into a dedicated Treasury foreign exchange account through Central Bank (CBSL) market purchases. CBSL balance sheet should be integrated with this special account, preventing its liabilities outstripping assets. This can secure the capital required to launch a transformation in agriculture and industry that this discussion seeks to address.

Use of agrochemicals and yield

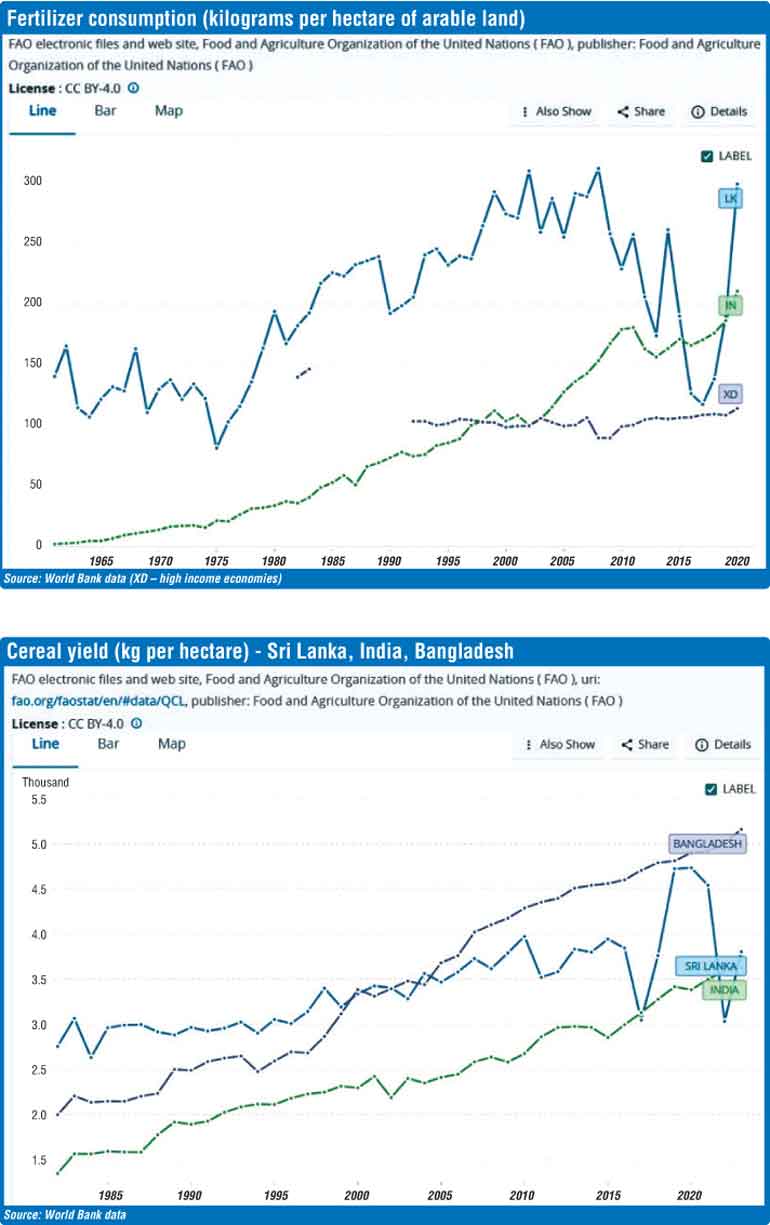

Two interconnected issues are crucial when understanding the structure of paddy agriculture in Sri Lanka and its overextension. Firstly, Sri Lanka’s agriculture as a whole is using over 50% more fertiliser per acre compared to India while yielding less per acre. The average fertiliser use in India and high-income economies is approximately 210kg and 114kg per hectare respectively, while Sri Lanka surged to nearly 300kg/hectare by 2020 from nearly 150kg/hectare in 1980 (see graph below). This massive increase in chemical input has not translated into better yields. Since 1980, while fertiliser use per hectare surged 100%, aggregate cereal yields shown by the FAO UN increased significantly less from 3 to 3.8 tons per hectare (see graphs below). This coupled with the rise in the share of total land under agriculture emphasised earlier shows that Sri Lankan farmers were moving into less fertile, marginal lands -areas that require more chemicals just to maintain baseline yields.

Source: World Bank data (XD – high income economies)

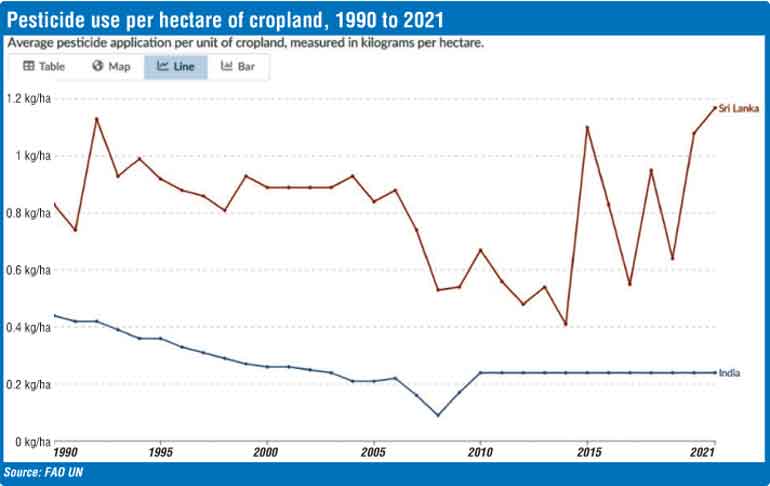

Source: World Bank data The same pattern holds for pesticides. Sri Lanka uses 1.08kg/acre compared to India’s 0.24kg/acre, which is well over four times (see graph below). This environmentally and biologically hazardous level of chemicals application likely contributes to the high prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Etiology (CKDu) among Sri Lankan farmers, while per hectare yield of cereals and paddy remains low compared to India’s approximately six to seven tons per hectare in some high yielding paddy lands. It is important to note that aggregate data for cereal yields may not fully reflect India’s higher paddy yields due to the aggregation effect with other, low-yielding grains. In spite of the low fertiliser use in India the incidence of CKDu among farmers has been on the rise recently while remaining below Sri Lanka’s percentage. The significant increase in the application of fertiliser since 2000 could potentially explain this trend. Source: FAO UN

Hazardous application of agrochemicals hand in hand with lower yields escalate unit production cost and the cost of food of the domestic workforce in the absence of cheaper food imports from the region. Sri Lanka in this context needs to release at least 20% of its paddy land (around 350,000 acres) -specifically the low-yielding, flood-prone areas encroached upon in recent decades- without a serious drop in output and transition the workforce into higher-quality non-agrarian employment.

Historical misconceptions and soil realities

This issue of higher agrochemicals application in Sri Lanka, insufficient yields and the resulting higher food costs is further compounded by the unfavourable climatic and soil conditions in the North Central Province (NCP) which supplies nearly 40% of country’s paddy output. As the late Dr S. B. D. De Silva often noted, unlike in the riverbeds of India or Bangladesh where paddy cultivation is carried out which are naturally replenished by slow overflowing rivers, Sri Lanka’s dry zone lands are subjected to flash floods and torrential monsoonal rains preceded by long spells of scorching dry weather, which tend to leach out the nutrients of the less cohesive soil. Reiterating this position, R. L. Brohier, Chairman of the Gal Oya Development Board, in 1941 noted that ‘[NCP] receives from 50 to 75 inches of rain during the year, but, instead of being distributed, the great bulk of it falls during the periodicity of one monsoon. Long and severe droughts are by no means unknown. No combination of physical conditions could have offered greater natural disadvantages for irrigation’ (History of Irrigation and Agricultural Colonization in Ceylon, 1941).

Sri Lanka urgently needs to uncover ways of reducing its landmass and workforce under agriculture, without stoking inflation, a drop in food availability and foreign reserves, while at the same time generating qualitatively acceptable employment outside agriculture. If we fail to do so, the requirement for emergency assistance and reconstruction due to climate disasters will become a permanent feature, given the high possibility of such future disasters

Following the 1935 soil chemistry findings of the Thopawewa and Parakarama Samudra Development Scheme, Brohier warned that the dry zone soil structure is not entirely suited to carry out large-scale resettlements centred on paddy cultivation. He noted that the ‘luxuriant tropical forest’ of the dry zone was a mirage of fertility caused by perennial plant foliage, and not by the soil itself. This vibrant plant growth in the uninhibited land in the dry zone misled the ancient settlers to believe that the soil itself was fertile. Once cleared for seasonal paddy, the soil exposed its inherent deficiencies. Historically, this weakness may have likely left the civilisation vulnerable to invasions due to the difficulty of sustaining a large standing army on a fragile food base. Brohier noted this paradox: ‘the growth of the trees led one to infer that the soil should surely be the richest, the analysis disclosed quite the reverse… in these circumstances, the soil reconnaissance of the Topawewa and the Parakrama Samudra Scheme confirms, and the report emphasizes, that in the event of the secondary soil [lower grade soil] being developed in paddy, it will follow that crop yields must necessarily be poor. Apparently the soil composition in these areas is more congenial for growing fruit trees such as coconut or citrus’. Emphasising the comparative disadvantage in the soil structure of the NCP he further states that ‘the secondary paddy soil in the Topawewa area from the same comparative standard can be placed only in the third class of Malayan paddy soil’ (page 46-47). The market mechanism and the ambitions of the political elites failed to account for these geological disadvantages, incentivising an expansion of paddy farming that now threatens both the national economy and the environment.

Some lessons from Indian agriculture: small-scale mechanisation and new techniques

Secondly, the seasonality of agriculture and its intricate relationship with the broader environment do not warrant the simplistic market led determination of its flow of resources based on individual profitability. The lower application of agrochemicals specifically in India’s paddy agriculture is an ongoing process, orchestrated by the Indian state Governments, and is not an outcome of free interaction of market forces. By adopting Direct Seeded Rice (DSR) using small-scale machinery, which drills seeds directly into the soil rather than using traditional broadcasting or transplanting, farmers have reduced the water consumption by 15% to 20%, reduce methane emissions, and simultaneously freeing labour from the cultivation process. The Punjab Government, for instance, actively plans to expand this technique to cover 700,000 acres across the state. Furthermore, paddy farmers in India use small-scale weeding machines instead of weedicides, made possible by the DSR method. Unlike the broadcasting method predominantly practiced in Sri Lanka, the use of a seed driller ensures uniform spacing between the rice plants. This allows greater sunlight absorption, which enhances the yields and reduce the duration required for the crops to mature. Additionally, this uniform spacing between the plants facilitates mechanical weeding, a process that uproots weeds and integrates them back into the earth, thereby converting them into organic matter.

These streamlined techniques hand in hand with alternate wet dry method of water use (which is now promoted by UNDP in Sri Lanka) have contributed to the increase in India’s paddy yield. This shift effectively converts working capital previously spent on agrochemicals, water and labour (wages), into fixed capital in the form of small machinery. Consequently, Indian farmers have successfully replaced the use of agrochemicals with a combination of mechanical tools and a more sophisticated understanding of cultivation and environmental factors. This structural shift reduces the production costs and the cost of food for the non-agricultural workforce. Simultaneously, the labour freed by introducing new machinery into agriculture is reabsorbed within the industrial sector.

This is an effective mechanism in reducing the marginal paddy lands by 20% without critically reducing the output, stoking inflation or increasing unemployment. To support this transition, compensation must be provided for farmers who will relinquish their less fertile marginal lands for reforestation. Another possible option would be to reduce or eliminate seafood exports to prioritise domestic consumption. This will reduce the nation’s dependence on staple grains while increasing the nutrition profile of the general population and reducing agricultural land. If Sri Lanka fails to adopt such State-led restructuring, the need for emergency assistance due to environmental disasters will become a permanent agonising feature of the national economy.