Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 1 September 2025 00:38 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Patalee Hettiarachchi and Gagana Kulathunga

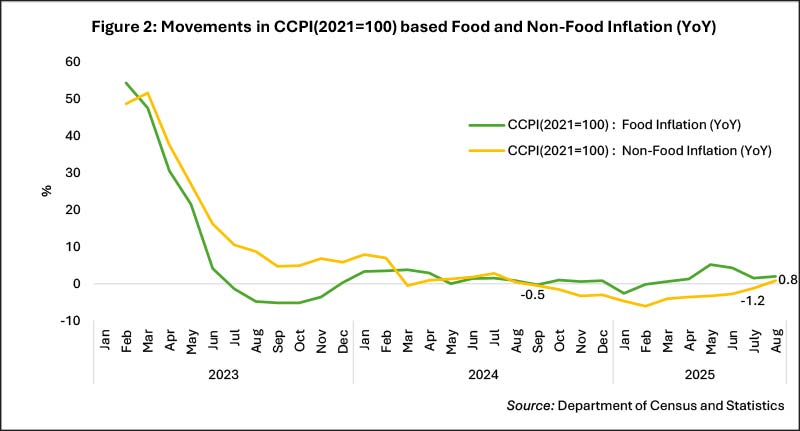

Headline inflation, as measured by the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI), returned to positive territory in August 2025, recording 1.2% (YoY) (Figure 1). This marks the end of a deflationary phase that lasted nearly a year. CCPI based headline inflation slipped into negative territory in September 2024 and remained negative for 11 consecutive months. The lowest point was reached in February 2025, recording a deflation of 4.2%. The deflationary trend gradually eased from March 2025 onward, culminating in a turnaround by August 2025 with headline inflation reaching positive levels.

Headline inflation, as measured by the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI), returned to positive territory in August 2025, recording 1.2% (YoY) (Figure 1). This marks the end of a deflationary phase that lasted nearly a year. CCPI based headline inflation slipped into negative territory in September 2024 and remained negative for 11 consecutive months. The lowest point was reached in February 2025, recording a deflation of 4.2%. The deflationary trend gradually eased from March 2025 onward, culminating in a turnaround by August 2025 with headline inflation reaching positive levels.

While the recent deflation was driven by supply-side factors, prolonged period of deflation is not conducive to economic recovery. Accordingly, the return of inflation to positive levels is a significant milestone in Sri Lanka’s progress towards achieving and maintaining the 5% inflation target. This article aims to examine the drivers of the deflationary episode, the factors behind the recent recovery, and the implications for monetary policy and the broader economy. It also reviews core inflation dynamics, differences between CCPI and NCPI, and the policy response of the Central Bank, providing a comprehensive picture of the inflation landscape.

High inflation in 2022 and 2023

Sri Lanka experienced its worst inflationary crisis in 2022, with CCPI based headline inflation peaking at 69.8% in September 2022 – the highest level on record. This surge was driven by multiple factors: sharp depreciation of Sri Lanka Rupee against the US Dollar, global commodity price shocks, long-overdue corrections in domestic fuel and electricity pricing, foreign exchange shortages, supply chain disruptions and amendments to tax structure including Value Added Tax (VAT) amendments. The crisis was further compounded by policy missteps, including sudden shifts in agricultural policy, heaving reliance on domestic financing, including monetary financing, by the Government, and delayed adjustments in the exchange rate.

In response, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka undertook aggressive monetary tightening, while the Government implemented fiscal reforms under the IMF-supported program. These measures, alongside improvements in foreign exchange liquidity, easing global commodity prices and improved domestic supply conditions led to a rapid disinflationary process. By mid-2023, inflation had fallen to single digits supported by appropriate policies in a period of less than one year from the peak inflation in 2022. Thereafter headline inflation broadly stabilised around the target of 5% during the second half of the year.

From disinflation to deflation (2024–2025)

Following a brief uptick in inflation at the beginning of 2024, driven by VAT amendments, substantial reductions in administered prices – electricity tariffs, petroleum and gas prices triggered a fresh decline in inflation. Combined with favourable statistical base effects, these reductions eventually pushed the economy into deflationary territory by September 2024, where it persisted until July 2025.

Non-food and supply-side drivers of deflation

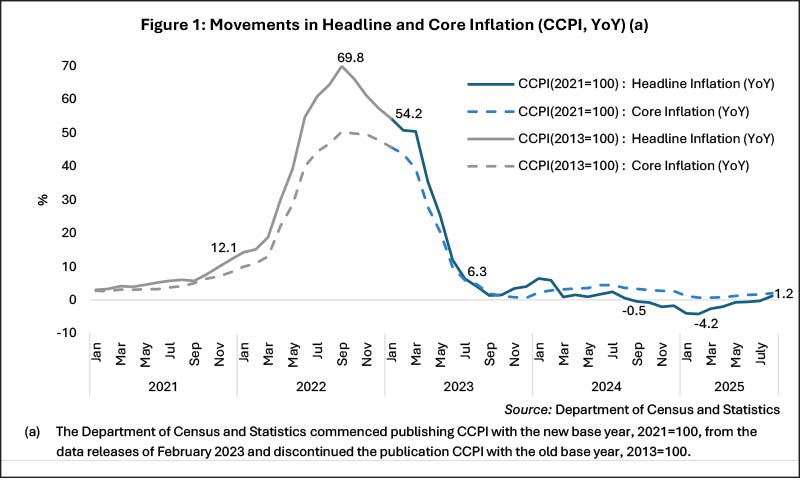

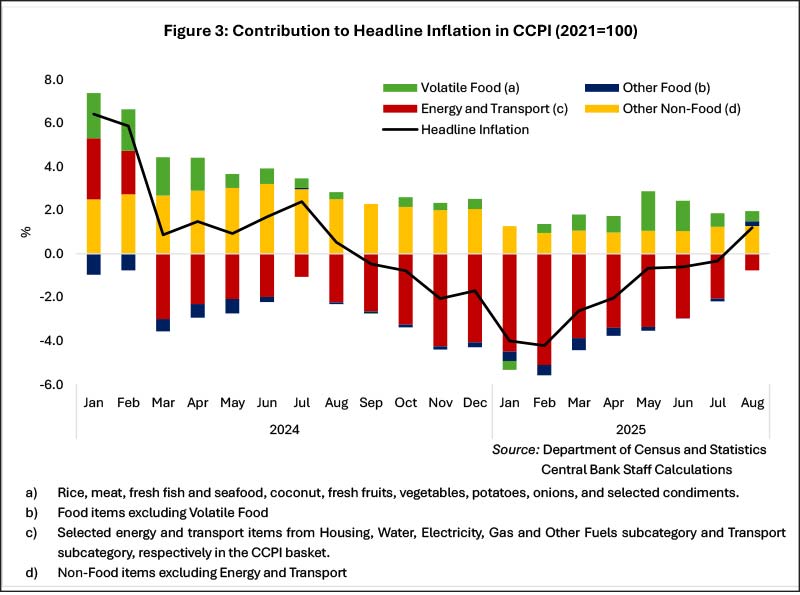

The deflation observed between September 2024 and July 2025 was primarily influenced by non-food items and supply-side factors, particularly sharp reductions in energy prices. Several rounds of electricity tariff reductions implemented between March 2024 and early 2025 played a major role in lowering headline inflation directly. Cost reflective fuel price adjustments were also made in several instances, reinforcing the deflationary trend.

As a result, non-food inflation remained negative between September 2024 and July 2025 (Figure 2), though the negativity began to narrow since March 2025 contributed largely by the statistical base effect. In addition, upward revisions to the electricity tariff in June 2025 also contributed to this. Sub-category analysis shows that Energy and Transport consistently accounted for the largest negative contributions to overall inflation, highlighting the supply driven nature of the deflationary episode (Figure 3).

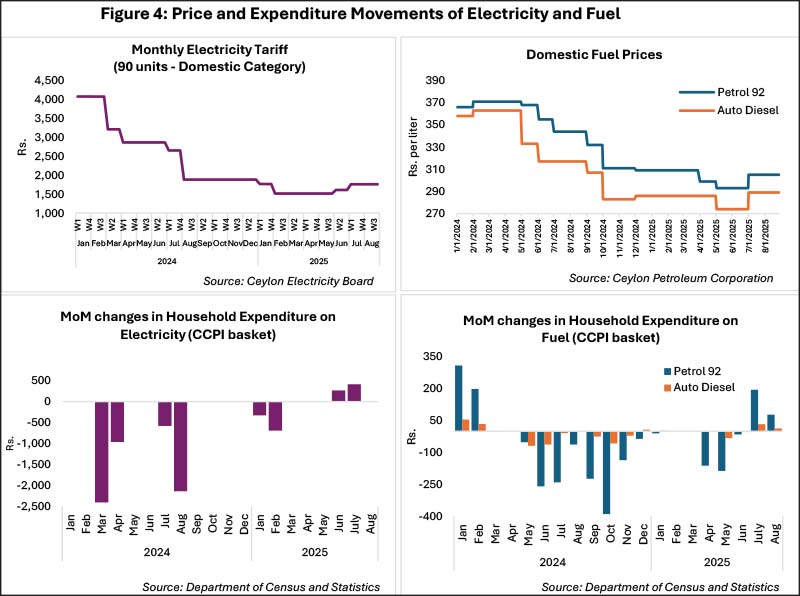

Electricity tariff, which is a major component of household expenditure, underwent several rounds of successive reductions since March 2024. The first significant revision was made on 5 March 2024, lowering electricity tariffs by an average of 21.9%. This was followed by a further reduction of 22.5% on 15 July 2024. A third downward revision on 18 January 2025 further eased household electricity expenditure by an additional 20.0%. In the case of a domestic household consuming 90 units,1 the combined impact of the March 2024, July 2024 and January 2025 revisions translated into electricity bill reductions of 29.8%, 34.3%, and 19.6%, respectively. Figure 4 depicts the changes in the 90-unit electricity bill and the month-on-month changes in household expenditure on electricity as considered in the CCPI.

Domestic prices of Petrol 92 and Auto Diesel were increased in January 2024 in line with the removal of VAT exemptions. However, they were subsequently subjected to multiple downward, cost-reflective revisions in line with falling global oil prices and the appreciation of the Sri Lanka rupee. By the end of 2024, Petrol 92 and Auto Diesel prices had fallen by 10.7% and 13.1%, respectively, compared to end 2023. These fuel price cuts directly reduced transport costs and indirectly contributed to lowering prices of other items through second-round effects. For instance, bus fares were reduced twice in 2024 – by 5.07% on 02 July 2024 and 4.24% on 02 October 2024 following declines in Auto Diesel prices. Figure 4 depicts the changes in domestic fuel prices and the month-on-month changes in household expenditure on fuel as considered in the CCPI.

While the primary contribution to deflation came from the transport and energy sectors, food prices also remained largely moderate during the period under consideration. Price pressures from imported goods remain muted due to the appreciation of the Sri Lanka rupee in 2024, which lowered the cost of non-energy imports. Meanwhile, the statistical base effects from the Value Added Tax (VAT) adjustments implemented in January 2024 also contributed, deepening deflationary conditions in early 2025.

Core inflation dynamics

CCPI based core inflation, which excludes volatile food, transport and energy prices reflecting the underlying inflation trends in the economy, tells a different story. Core inflation gradually declined during the second half of 2024 and early 2025, reaching 0.7% in both February and March 2025 – the lowest point during the period under review. From April onwards, the downward trend reversed, with core inflation gradually rising to 2.0% by August 2025.

This pattern suggests that, while headline inflation experienced significant deflationary pressures, underlying price pressures remained relatively stable. The moderation in core inflation being less than that in headline inflation indicates that the deflation was not broadly demand driven. Rather, it was largely the result of temporary supply-side factors such as energy price adjustments. However, the movement in core inflation was influenced by the second-round effects of energy and transport price revisions and exchange rate passthroughs during the period.

Significance of the shift back to positive inflation

The return of CCPI based inflation to positive territory in August 2025 is a notable development for both policymakers and households. Prolonged deflation can signal weak demand, reduced investment, and economic stagnation. In Sri Lanka’s case, however, the deflationary phase was primarily supply driven. The turnaround in August 2025 indicates that the economy has absorbed supply shocks, and that energy and transport price adjustments have stabilised.

For businesses, the return of positive inflation reduces the risk of deflationary expectations, which can delay spending and investment. For households, this means that the aggregate price level will continue to rise, but at a moderate level and in a controlled manner. It is also noteworthy that the mild deflation that the country has experienced for several months has provided some temporary relief to households and businesses recovering from the prior inflationary shocks.

Differences between CCPI and NCPI

It is noteworthy that CCPI based headline inflation turned positive later than NCPI based headline inflation. This reflects differences in consumption basket composition: CCPI represents an average urban household in Colombo and has a higher Non-Food share, whereas NCPI, which measures nationwide inflation, places relatively greater weight on Food.

Since the deflationary trend was concentrated on Non-Food categories such as energy and transport, CCPI based headline inflation remained negative for longer. In contrast, NCPI, less exposed to these sectors, recovered earlier. This divergence highlights how household spending patterns influence inflation readings across different indices and underscores the importance of considering both urban and national measures when analysing price trends.

The remedial actions taken by the Central Bank

Central banks typically face significant challenges when dealing with supply shocks, which are often characterised by sudden changes in production costs due to factors beyond the fluctuations in demand conditions. Because monetary policy mainly influences demand-side inflation pressures and operates with a lag, central banks usually adopt a cautious stance toward isolated or transitory supply shocks, avoiding aggressive interventions that could exacerbate economic volatility. However, if supply shocks persist or trigger second round effects that de-anchor inflation expectations, central banks may be compelled to intervene pre-emptively to maintain credibility and price stability.

In Sri Lanka’s case, the accommodative monetary policy stance adopted by the Central Bank in mid-2023 was continued to counteract deflationary pressures. The policy interest rates were further eased in the second half of 2024, as well as the first half of 2025, to support steering inflation towards the target, while fostering economic recovery. Market interest rates fell in line with policy easing, promoting credit growth in the private sector. Open Market Operations were used to ensure that money market interest rates are well aligned with policy objectives. However, the Central Bank monitored the developments both domestically and globally to avoid overstimulating demand in an economy still adjusting to supply-side shocks.

Outlook for inflation

As per the latest inflation projections of the Central Bank, as published in the Inflation Fan Chart,3 CCPI based headline inflation is expected to remain positive for the remainder of 2025, gradually approaching the inflation target of 5%. The recovery is supported by the stabilisation of energy and transport prices, the gradual rebound in demand conditions, and the ongoing accommodative monetary policy stance. Core inflation is also anticipated to rise gradually and maintain lower volatility. However, the outlook is subject to uncertainties, including global energy and food price volatility, and geopolitical tensions.

Major upside risks include possibility of higher-than-expected domestic demand, possible adverse weather conditions affecting agricultural production, possible increases in global commodity prices, and possible depreciation of Sri Lanka Rupee. Downside risks include weaker global demand, which could reduce energy prices and possible further reductions in food prices in the near term amidst a healthy harvest.

Conclusion

The return of inflation to positive territory in August 2025 marks the close of one chapter and the beginning of another in Sri Lanka’s inflation journey towards achieving and maintaining its inflation target of 5%. After a period of historically high inflation in 2022, followed by rapid disinflation and a nearly a year of deflation, the economy is now transitioning towards a more stable and balanced inflation path. The sharp changes over the past three years from extreme inflation to temporary deflation reflect the combined effects of domestic supply-side factors including long overdue corrections in administrative prices, monetary and fiscal policy reforms, and evolving external conditions, including global commodity prices and exchange rate movements on the price stability.

Ultimately, it is a reminder that price stability is not an endpoint, but a continuous process of managing risks, shocks, and expectations, requiring careful monitoring and forward-looking policy measures.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Vishuddhi Jayawickrema of the Statistics Department of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka for the insightful comments and guidance.

Footnotes:

1Electricity tariff of 90 units in the domestic category is considered in compilation of the CCPI (2021=100) and NCPI (2021=100).

2As per the inflation Headline Inflation Projections published in the Monetary Policy Review: No. 04 – July 2025 Press Release (available at: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/sites/default/files/cbslweb_documents/press/pr/press_20250723_Monetary_Policy_Review_No_4_2025_e_Cw6e5.pdf).

(Patalee Hettiarachchi is a Senior Assistant Director of the Statistics Department of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Gagana Kulatunga is an Assistant Director of the Statistics Department of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. The views presented in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.)