Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 18 November 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

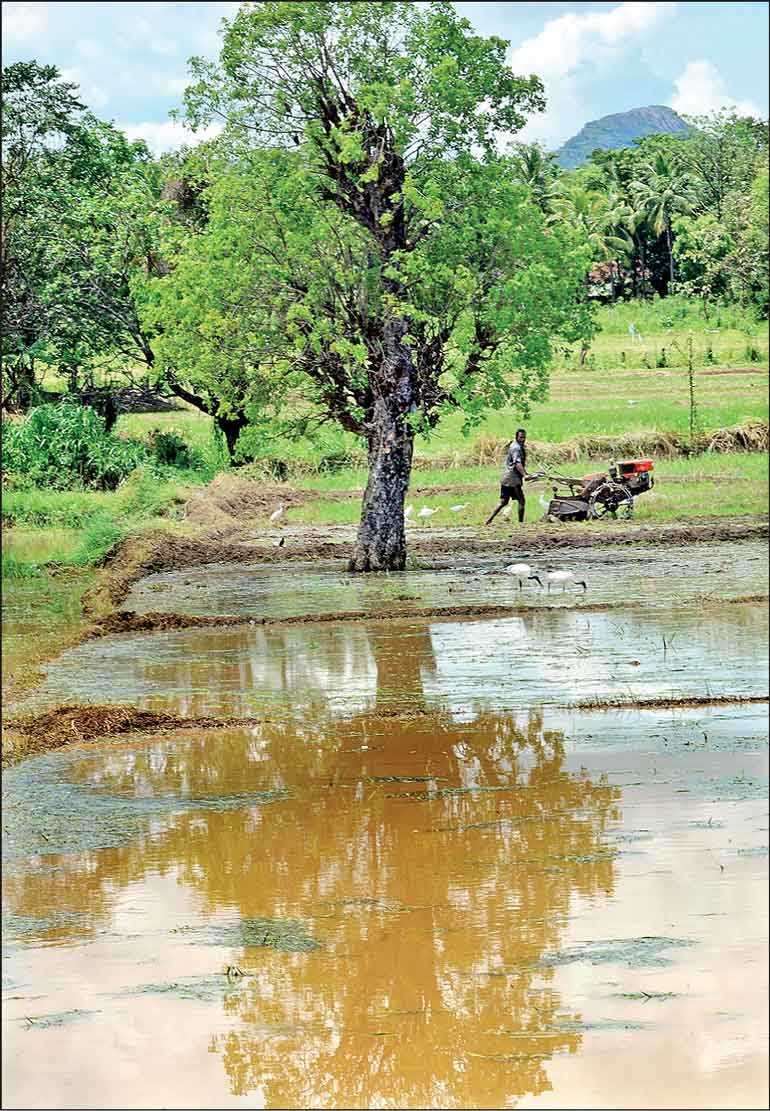

In Sri Lanka, 82.25% of the country's land is owned by the State while only 17.75% is privately owned, reflecting a history of centralised control over land. This 82.25% of land belongs equally to the 22 million people of the country living now and the future generations yet to be born. This land is held in trust by all governments on behalf of both components of owners. A land policy therefore cannot benefit a few ministers and parliamentarians and their dependents, but the current and yet to be born Sri Lankans – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Bim Saviya, the MCC Agreement and now a directive on “residual” land has muddied the waters in relation to State land policy and management

Land management in Sri Lanka appears to be all over the place. Several ministries and Government departments appear to be responsible for State land management including for forests management, wildlife conservation area management, residual land management (latest to hit the headlines, see below), agriculture land management and tea, rubber and coconut land management.

The latest headline grabbing news item in the LankaWeb News ‘Circular enabling Government to hand over forests to companies enforced’ on 9 November states that “In a blatant move of violating eco-conservation laws, the Government has issued a circular, 1/2020, enabling them to hand over lands to multinational companies and businessmen, by revoking the Circular ‘05/2001,’ ‘02/2006,’ ‘5/98’ issued for the protection of the remaining remnant forests for the acquisition of lands required for the National Physical Plan implemented till 2050 and for the release of lands for the implementation of the MCC Agreement.”

The circular referred to here may be in respect of whatever is termed “residual” land, but the absence of a transparent policy has given rise to suspicion and speculation on the intent of successive governments about their designs on State land. The real intent of the MCC Agreement has been in question and many have questioned the bona fides of this agreement.

A report on the land tenure considerations in Sri Lanka’s Proposed National REDD+ Strategy by the Sri Lanka UN-REDD Programme in April 2016 states that in Sri Lanka, 82.25% of the country's land is owned by the State while only 17.75% is privately owned, reflecting a history of centralised control over land.

This 82.25% of land belongs equally to the 22 million people of the country living now and the future generations yet to be born. This land is held in trust by all governments on behalf of both components of owners. A land policy therefore cannot benefit a few ministers and parliamentarians and their dependents, but the current and yet to be born Sri Lankans.

Neither can a land policy benefit a country other than Sri Lanka. Selling State land to foreigners will not benefit Sri Lanka. In fact, it will have a negative effect in the long term.

It is presumed that State lands include forest land, wildlife conservation lands, wildlife lands, agriculture land and estate land that belongs to the State, unproductive land distributed amongst these (probably what is termed residual land) and other classified lands. It is not clear whether temple, church, mosque and kovil land is included as State land.

One of the Parliament Acts that has kindled the fires of suspicion regarding vested interests and ulterior motives, is the land registration Act aka Bim Saviya, introduced in 1997 and implemented in 2007. This has so far registered only 0.72 million blocks out of 12 million blocks of land. This registration is less than 5% of the total number of blocks identified. It has taken 12 years to achieve this.

A question arises what land is being registered. Is it the 82.25% which is State land or the 17.75% which is private land? It is said that the registration procedure is very cumbersome and does not recognise Sri Lankan context laws, customs and practices, as the law is based on the Australian Torrens title registration law. The next question that arises is why State land registration is cumbersome and whether there is a need to issue titles for State land.

The land component of the MCC Agreement is insistent on land titles being registered under Bim Saviya. If State land registration has to be done according to Bim Saviya, it could be interpreted that the MCC Agreement is all to do with State land, and as increasing productivity of State land is not directly related to its title, it can be assumed that issuing titles for State land has an ulterior motive. After all, it is State land, and the suspicion that the real intent of the MCC Agreement is to get the government to privatise State land by selling them to locals and foreigners is not unfounded.

The latest salvo in land management with a circular referring to “residual” land again raises suspicion as to what might be regarded as “residual” land, especially as its management including disposal for development work, has been assigned to Provincial and District Secretaries. It is well known that political pressure and influence over these officials is rife in Sri Lanka and that boundaries on the so-called residual land could expand into forests and wildlife conservation areas. Development work could mean different things to different people. Cutting down valuable trees in a forest, now reclassified as residual land, might be regarded as development work by some!

The influence and pressure that politicians exert over all segments of the administrative service is known. Politicians in general do not enjoy the trust of the people as most are known to initially cover the costs associated with their election once in power and thereafter accumulating enough wealth for themselves and many generations to come. Little do they realise that their future generations may not have a country to call their own if land is sold to foreigners or a world to live in if the damage they do to the environment for some immediate gain continues.

A land policy must essentially be on the basis of (a) obtaining more with less, not the other way about. Using less land to produce more will ensure something is left behind for future generations as there will not be any land left if more and more land is used by the present generation. (b) Research must be the cornerstone for increasing productivity as countries like Israel has shown with great success (c) increasing forest cover and not reducing it. Forest cover will save the environment and the climate (d) and wildlife sanctuary land being increased and not decreased as these play a significant role in the sustainability of the eco system.

A land policy has to be for the long term, for generations yet to be born, hence the need for a strategic policy. It needs to be transparent as it is not something for today’s custodians to hide from the true owners, the present and future generations of the country. The current owners of State land, through their votes must also have a say in what they intend leaving behind for the yet unborn generations. There cannot be a place for secret deals that circumvent scrutiny and responsibility.

Finally, once a comprehensive State land policy is determined by the people through their representatives, both at central level and provincial level, its management should be assigned to administrators to implement without fear or favour.