Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Tuesday, 30 December 2025 00:53 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The strong and authoritative State prior to Independence had sufficient foreign exchange from the growth of export plantations to import the required consumer goods to satisfy the country’s demand and to keep the dual economy going in different directions without interruptions or social unrest. This positive balance of trade began to change dramatically in the early 1950s with a rapidly rising demand for foods from the fast-growing population and escalating cost of food imports against falling prices and earnings of commodity exports. As a result, post-Independent political authorities have confronted the declining capacity of the Sri Lanka State in their attempts to compete for power by implementing populist welfare-driven, often economically irrational, political agendas. Political concerns became prominent rather than economic ones as a result of persistent scarcity of capital for investment.

The strong and authoritative State prior to Independence had sufficient foreign exchange from the growth of export plantations to import the required consumer goods to satisfy the country’s demand and to keep the dual economy going in different directions without interruptions or social unrest. This positive balance of trade began to change dramatically in the early 1950s with a rapidly rising demand for foods from the fast-growing population and escalating cost of food imports against falling prices and earnings of commodity exports. As a result, post-Independent political authorities have confronted the declining capacity of the Sri Lanka State in their attempts to compete for power by implementing populist welfare-driven, often economically irrational, political agendas. Political concerns became prominent rather than economic ones as a result of persistent scarcity of capital for investment.

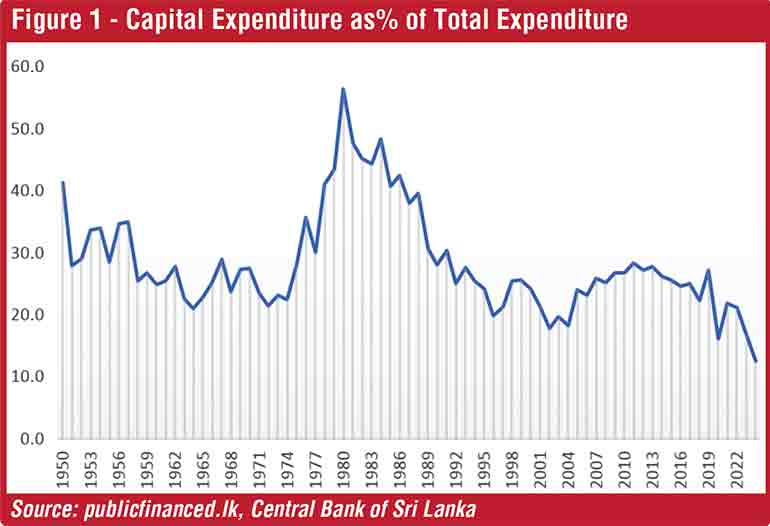

Capital expenditure of the State since 1950 gradually declined from 41.3 % of the total expenditure to 21.6% in 1972 and suddenly elevated to the historic highest level of 56.6% in 1980. This was due to heavy investments in large construction projects like the Mahaweli Multi-Purpose Development Projects with the opening up of the economy under market liberalisation policies in the late 1970s. Ever since, capital expenditure of the State drastically declined to 12.7% in 2024, the lowest since Independence. By contrast, high levels of welfare spending have contributed to progressively enlarge the size of budget deficits, draining scarce resources away from investment to consumption (see Figure1). Ever-growing recurrent expenditure on the other hand consumed more than 85% of State revenues by 2024.

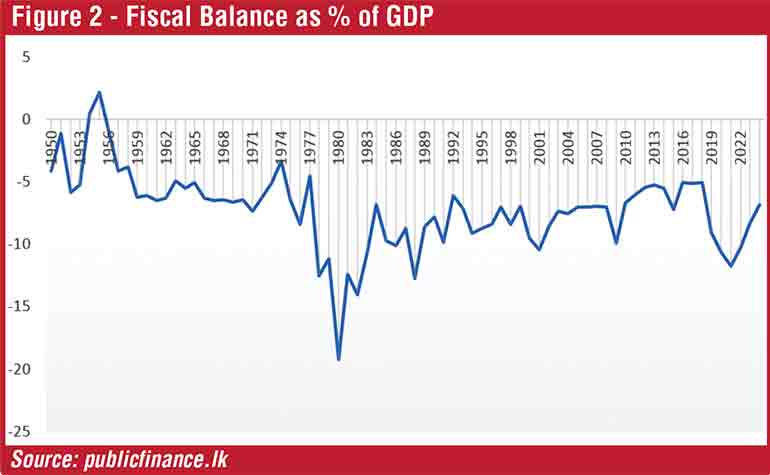

This trend of capital erosion contributed not only to weaking the revenue generating capacity of the State but to also growing the fiscal deficit constantly during the entire second half of the 20th century (1950-2000) and the first quarter of the 21st century up to 2024. Except in the year 1955, which recorded a surplus fiscal balance due mainly to the sudden rise of tea prices in the export market (tea boom), in all years from 1950 up to 2024, Sri Lanka’s fiscal balance remained constantly negative. On average it has been 10% of GDP throughout the non-conventional modern era (2001-2024) of the 21st century. Exceptionally high fiscal deficits have been recorded after entering into an open/liberalised market economy in the late 1970s and during the post-pandemic economic crisis in 2021/22 (see Figure 2). Irrespective of those contrasting situations the fiscal deficit continued to rise significantly. The State as the key administrative mechanism overall is in decline as the political authorities have not been able to move its functional activities away from their politically pledged welfare-oriented consumer spending agendas to investment.

As a result, a critical need for infrastructure maintenance and development, economic diversification with entrepreneurship building and innovation-led output expansion were either left out or postponed.

External pressure to pay debt against internal pressure to spend more for better living

We are entering the second quarter of this century with bitter experiences of economic, social, health and political disasters. Historic downfall of the economy began with the Easter bombing in 2019, followed by the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak in 2020 and ended with the worst economic crisis in 2022. Sri Lanka lost resilience to external shocks and the political authority failed to manage the crisis. Now, at the beginning of the second quarter of this century, we are still living with uncertainties, disappointments, frustrations and economic insecurity at household level while our political leaders, policy-makers and financial experts are busy preparing the ground conditions to be aligned with the IMF-regulated recovery process. External pressure is more towards achieving time-bound targets of increasing Government revenue and slashing expenditure to ensure servicing of foreign debt/debt sustainability and repayments. Internally, pressure is mounting to meet high public expectations for better living and to solve deepening problems involved in deteriorating living conditions and deprivation of livelihoods among the largest segment of middle and lower income earners. Middle class status of living is fading away with the majority in the middle-income dropping down to poor status of living while the poor are getting squeezed down below the poverty line in their struggle to combat poverty and starvation.

A radical change is needed to transform rural small agricultural holdings into diversified small mixed farming enterprises or units of productions with innovations and technological improvements. Addressing those problems depends on strong political commitments not to craft interventions for politics but to building a precious and self-sustained modern agricultural enterprise brick by brick

The new Government is strongly committed to delivering economic relief to those who suffer from unbearably harsh living conditions, address the dissatisfaction with the current economic situation and invest in urgent improvements to health and education. Only questions are how fast those commitments translate into action, at what cost and to what extent? Any delay or inaction will fuel public unrest.

The Government is grappling with difficult-to-balance and highly complex tasks of increasing revenue to satisfy IMF conditions related to debt sustainability/repayment with the next most critical task of spending more to satisfy urgent domestic needs related to relief measures, welfare, poverty reduction, upgrading living standards, improving health and education.

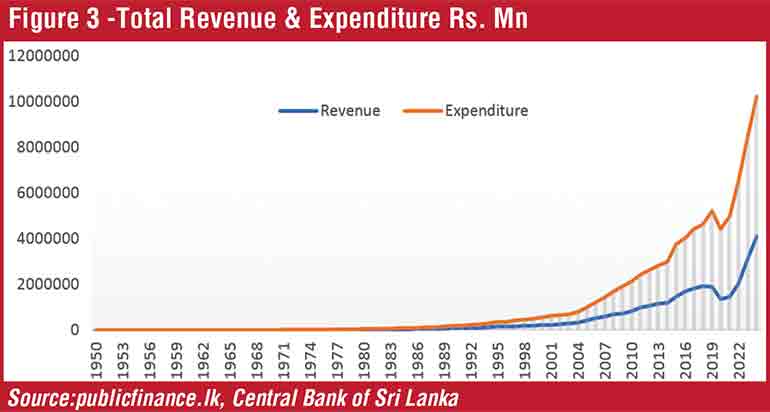

Widening gap between revenue and expenditure

Moving forward with those challenges, the Government is facing a difficult task of accelerating accumulation functions of the State to ensure revenue growth is higher than the growth of expenditure. However, from the beginning of the 21st century, Sri Lanka Government spending grew continuously much faster than revenue growth. In 2000, total revenue was Rs 216,427 million while expenditure grew much faster to Rs 335,823 million, which is Rs 146,722 million more than the revenue. At the end of 2024, total revenue increased to Rs 4,090,808 million while expenditure climbed far beyond up to Rs 6,130,739 million, which is Rs 2,039,931 million more than the total revenue (see Figure 3). The gap between revenue and expenditure of the State continues to grow much wider. In this respect, a radical structural change is needed not only for highly efficient management of State institutions and resources with good governance but also for creating a very impressive investment climate to attract foreign investment necessary to boost economic growth.

Collisions between slashing expenditure and increasing revenue

Challenges ahead are very much related to accumulation and legitimation functions of the State, how to increase tax revenues after having imposed very high direct and indirect taxes and how to cut down essential expenditure (mostly recurrent) further. Secondly, how to tackle interface problems emerging from possible collisions between measures to reduce expenditure and increase revenues. Resorting to borrowing, both internally and externally, was the only option available from the past to present to finance constantly growing fiscal deficits. In addition to the challenges emerging from ‘borrow in order to survive and survive in order to borrow’ type of trapped in debt cycle of fiscal deficit management, greatest pressures on ungovernable fiscal balance deficits now come from much wider areas of essential spending such as aging population, lower productivity, declining labour force participation, deteriorating the quality of human capital, political unpreparedness and inefficiencies of State institutions.

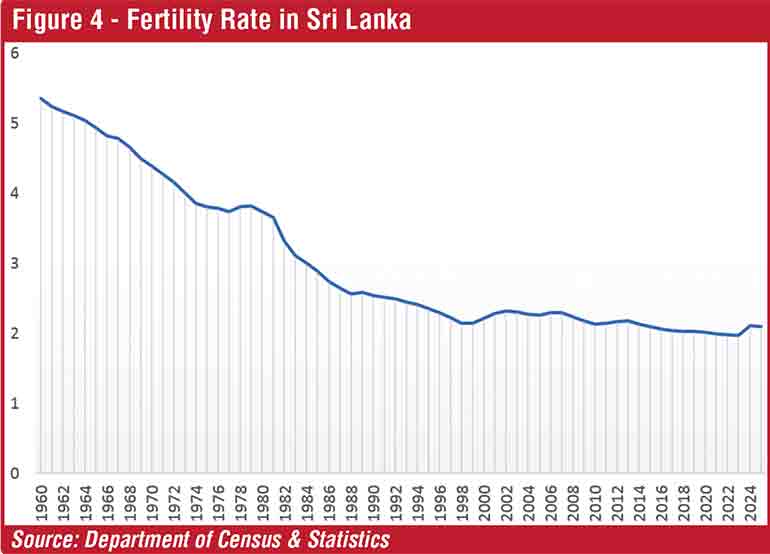

Declining fertility, rapidly expanding aging population and shrinking labour force

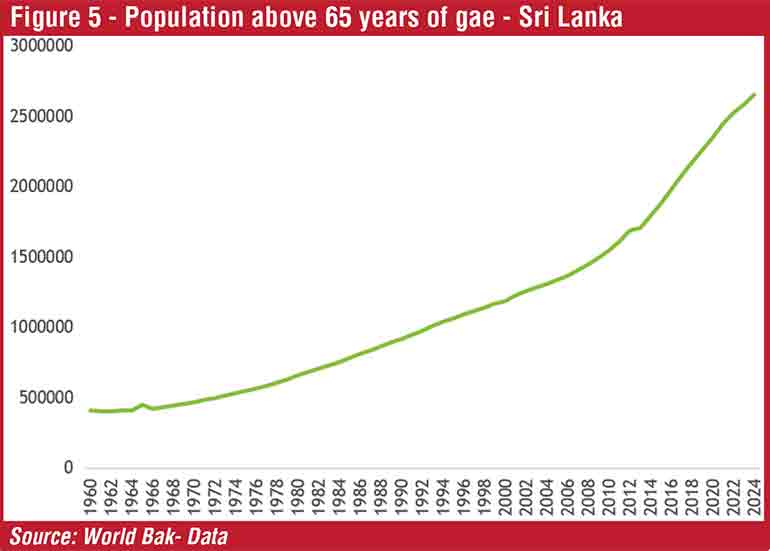

Sri Lanka is going through a rather unique demographic transition compelling the State to provide for more spending. The fertility rate in Sri Lanka has been falling significantly from 5,35 births per woman in 1960 to 1.97 births per woman in 2023. It is projected to be 2.1 births per woman in 2025 (see Figure 4). According to the current projections of the United Nations, global fertility will reach the replacement level of 2.1 births per woman by 2050. Sri Lanka has already reached this replacement level by now, a quarter century earlier than the projections. This means that no more children will be added to replace this generation with the next generation. Moreover, a shrinking of the active labour force will be an obstacle to productivity growth and economic expansion beyond 2025. While the population growth rate dropped to below zero level by 2024, the population aged 65 and above grew from 408,060 in 1960 to 620,543 in 2000 and then surged to 2,652,699 in 2024 (see Figure 5). This is the highest proportion of older adults in South Asia. By 2030, all baby boomers (born 1946-1964) will be aged 65 or older with a significant demographic shift causing a wide range of implications. This large segment of the adult population, projected to be 3,300,000 or 14,7% of the total population by 2030, will be a challenge to manage public spending with pressure not only on healthcare and the social system but also on the economy and budgetary management.

The leader of NPP claims the people’s mandate, asserts that their victory, reflects the will of the people and grants legitimacy to pursue policy goals. However, practical application is more complex and interpreted differently when the priority shifts from addressing people’s economic suffering to consolidate power by displacing established political parties. A new political style followed to retain power and remain popular is focused on differentiating the new ruling party and supporters as ‘pure and anti-corruption citizens’ against ‘corrupt and destructive political parties and their followers

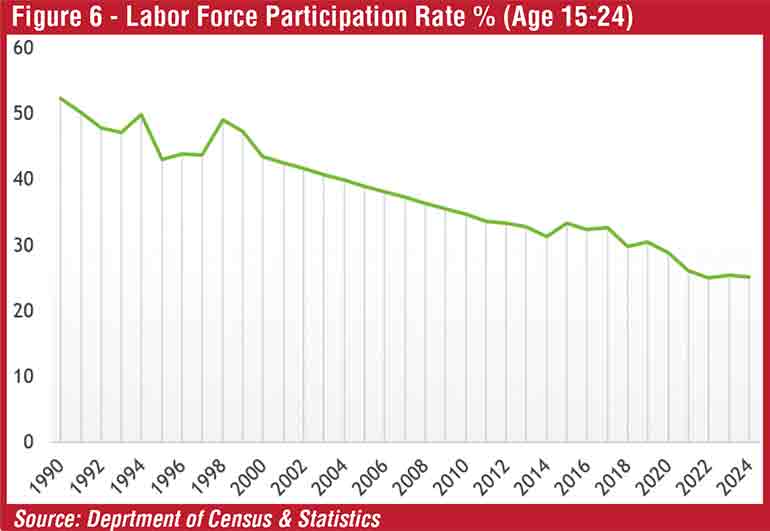

Apart from the declining population in the country, the economically active labour force will continue to shrink. The labour force participation rate declined significantly from 52.5% in 1990 to 25.3% in 2024(see Figure 6). This trend shows that the shrinking labour force will lead to slowing down revenue generation. Future potential for revenue growth is constrained by lower productivity, lower tax, lower national income, lower growth and lower savings. Predicting Generation-Z’s behavior is challenging for business due to their higher mobility, lower brand loyalty and decision-making by a mix of market, economy and social factors. Other factors contributing to a shrinking workforce include rising labour market inactivity, particularly among youth, and a decrease in overall employment growth. Rapidly expanding retired workers on the other hand create a higher cost burden to the State as the public sector pension payments will increase significantly and persist as an obstacle to reducing fiscal deficit and recurrent expenditure. As a result of improved life expectancy of senior citizens in the country due to free public health services, the oldest segment of people will increase with a high demand for elderly care and medical treatments. It was estimated that public expenditure on pension payments and social assistance is approximately three percent of GDP or more than 12% of Government revenue in 2024. This can be doubled by 2030 with the entire baby boomer employees retiring from the public service.

Migration pressure

Escalating migration pressure with rapidly growing domestic supply beyond the demand from abroad, accelerated the competition of skilled and unskilled workers finding job opportunities in foreign countries. This trend, although favourable for foreign exchange earnings, leads to increasing uncertainty in the domestic labour market and shrinks the domestic labour force further.

Another prominent migration trend is the outflow of young people for foreign education and ‘brain drain’ for better living. This tendency implies that the Government will face an acute problem of high-value human capital scarcity with an additional cost incurred for the investment in education and skills development of those who migrate permanently. The scarcity of high quality domestic workers could hamper economic growth and hinder economic progress. Lack of creative thinking, skills and expertise needed for rapid technological transformation could lead not only to slow down the decision-making process but also to long-term economic stagnation. Meeting the challenge of human capital scarcity management will be a difficult and costly task.

Declining productivity growth

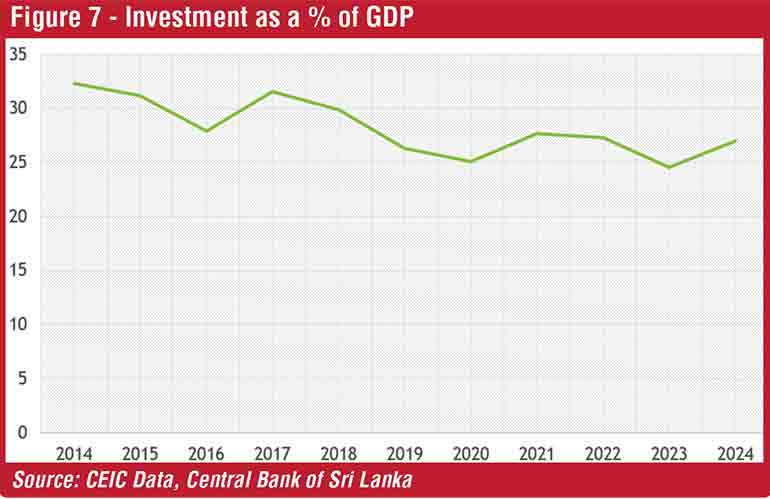

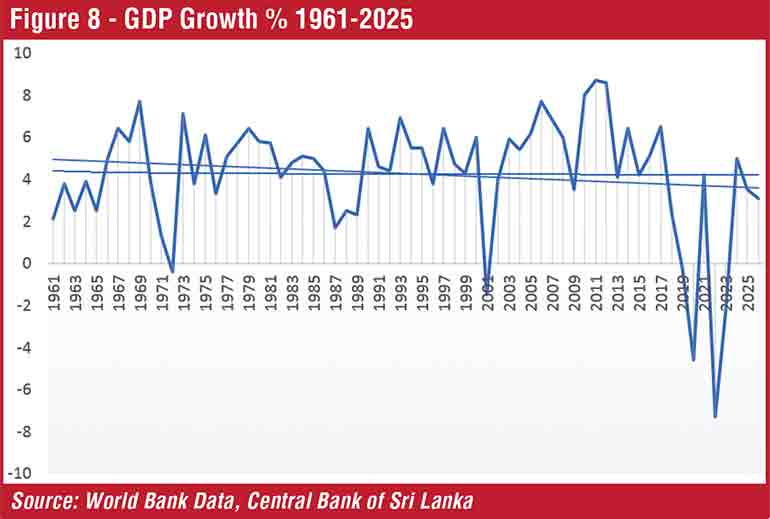

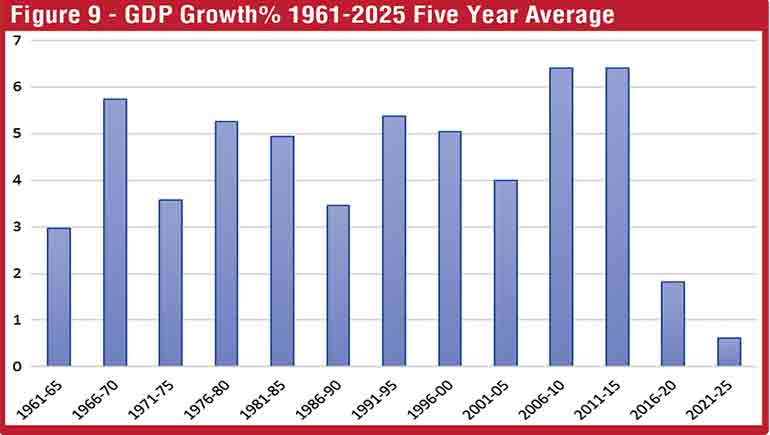

Given the declining capacity of the State with constantly rising public debt, rising recurrent expenditure and the limitations to rely on taxing people, the only option available to drive an economic growth trajectory is productivity growth. Although the urgency of productivity enhancement is widely recognised at development forums and economic discussions, turning those ideas or political commitments into action never took place due to capital scarcity stemming from the economic slowdown. Investments throughout the last decade gradually declined from 32.3% of GDP in 2014 to 27% in 2024 (see Figure 7). Therefore, significantly high-scale investment, both local and foreign depends very much on enhancing productivity (to be beyond 30% of GDP), entrepreneurship building with innovations and modern technological transformation (to sustain more than 6% GDP growth). However, the historic pattern of GDP growth in Sri Lanka shows a downward trend with deeper fluctuations to the extreme lowest negative growth of -7.3% in 2022 with the economic crisis. The average GDP growth is around 4-4.5% for the last 40 years of the 20th century and the first quarter of the 21st century (see Figure 8).

We cannot rely on the undiversified, constantly fragmenting, low-capital incentive, low-knowledge incentive and low-productive rural agricultural holding to boost economic growth. They are subjected to a productive and reproductive squeeze caused by the rising cost of living. They look powerless but most powerful in choosing or defeating political parties as the majority of voters represents the agricultural sector. In this respect, it is the fear rather than the power that political authorities are forced to divert State resources to satisfy rural agricultural producers to stay in power

The five-year moving average of the GDP growth from 1966-1970 to 2001-2005 displayed a declining trend. After having recorded an exceptionally high average growth of 6.4% for the periods of 2006-2010 and 2011-2015, a sharp decline of the five-year average GDP growth (impacted mostly by the economic crisis in 2022) was recorded for the period from 2016-2020 to 2021-2025 (see Figure 9). If the Government remains with a business as usual approach to sustain the existing low-growth, low-productive traditional sectors, falling into a low growth trap is unavoidable.

Productivity growth in Sri Lanka on average was 1.64% from 2013 to 2024, much lower than Bangladesh 3.37%, India 4.31% and Nepal 2.50%.

Contd. on page 12

(The author is former Director Research, People’s Bank, Head of Research & Development Bank of Ceylon and Senior Researcher UNDP Asia-Pacific Regional Centre. He could be reached via email at [email protected])

Medium, Small and Micro Enterprises (MSMEs), expected to drive the economy through increased investment, are in the status of bankruptcy since the Covid-19 pandemic and economic crisis. More than 90 percent of them are household level informal micro enterprises. Uplifting them by granting concessional credit will not be sufficient. Upgrading them with technological knowledge and entrepreneurial competencies to maximise efficiency and productivity is essential. Attracting FDIs (Foreign Direct Investment) will depend very much on the stable growth and scaling up of MSMEs. Their progress is constrained mostly by inefficient use of input such as labour, capital and raw material rather than less availability of physical and human capital. Second, the most important drawback is the lack of knowledge-incentive intangible assets such as technological capability, entrepreneurial skills, innovations, packaging, marketing and diversification

Political unpreparedness: From political populism to authoritarian populism

It is for the first time in Sri Lanka’s political history that a team of novices dominates Parliament and is expected to drive the State towards a new path to progress. Representatives of the new Government are strongly bound to ‘an alternate democratic mandate’ created by anger, frustration and suffering of the people and guided to fulfill the promises. Significant doubts have been raised about the political authority’s ability to heal economic “fault lines” instead of provoking hostility.

Most members of Parliament who represent the new Government have moved from their informal local politics at the periphery to join the new political authority at the center with formal power assigned. Their role in the parliamentary debates often demonstrate the continuation of their usual practice of political scrutiny of previous regimes and blaming the past to justify or cover up delays or weaknesses of the on-going activities. Most unskilled politicians use Parliament debates to provoke animosity rather than active participation in constructive discussions and negotiations. A popular mandate was granted on the ground that massive scale leakages of State resources by way of widespread corruption, mismanagement and misuse of public funds, which was marked ‘historic tragedy’, will be halted and funds saved by doing so will be invested to boost economic growth. The lower the Government’s ability to display constant economic progress, the higher the probability of public mistrust and damage to the credibility of the Government.

A new political approach to retain power and remain popular

The leader of the new political party (NPP) in power claims the people’s mandate, asserts that their victory, reflects the will of the people and grants legitimacy to pursue policy goals. However, practical application is more complex and interpreted differently when the priority shifts from addressing people’s economic suffering to consolidate power by displacing established political parties. A new political style followed to retain power and remain popular is focused on differentiating the new ruling party and supporters as ‘pure and anti-corruption citizens’ against ‘corrupt and destructive political parties and their followers’. One of the popular strategies involves persecuting and imprisoning previous ruling party leaders and threatening the rest of the members of traditional political parties for corruption and mismanagement of public funds. This attempt is interpreted as a people’s mandate to continue a genuine struggle of the Government with the people against enemies of the people.

Authoritarian populism–Eliminating bad politics means eliminating bad happenings in society

A charismatic leader with authority, political competencies and rhetorical capability can overexpose the links between bad happenings in society and bad politics of previous political regimes as a strategy to consolidate power and remain popular. Organising public meetings and communication with the media are used to highlight mistakes and failures of previous political leaders and disqualify all of them as enemies. Eradication of bad politics is rationalised as a measure to eradicate drug problems and vice versa. Using the authority to suppress competitive political parties can leads to violate democratic norms after having taken over the power through democratic means. The higher the provoking animosity and intensification of discrediting political opponents far greater the retaliatory actions, protests and interruptions. Costly confrontations with organised offensives are regular events and such a political battle would lead to damage the credibility of political leaders locally and country’s reputation internationally

Concluding remark– Common ground within diversity of politics to address critical national challenges to growth and stability

We are at a decisive moment on our way from crisis to growth. Our fiscal management is susceptible to external influence and conditions. Our possibilities to control constantly increasing debt are remote and we need to borrow mostly to meet growing essential recurrent expenditure. Lower capital expenditure means poor infrastructure, higher cost of production, lower productivity and lower competitiveness in the market. If borrowed funds are not utilised for revenue generation projects we will not be able to escape from falling into a debt trap.

We need to diversify our economy into high-growth sectors such as services, manufacturing industries, energy, knowledge and technology business enterprises. Our investment capacity is declining while capital erosion is continuing. If we fail to attract foreign investment, the dream of diversifying into high growth sectors will not come true. The direction of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is unclear and unpredictable as the flows into developing countries are diminishing to the lowest $ 435 billion recorded for 2023 after two decades.

Changing the political approach from ‘political populism’ to ‘authoritarian populism’ will lead to political instability rather than to stability. Our small Island cannot afford costly, wasteful and destructive political divisions, fragmentation and polarisation. We need justice more than arrogance, cooperation rather than division, respect than disgrace and we need a common ground within a diverse political setting for negotiation and collective efforts of all political leaders at national level to address urgent and most critical challenges to growth and prosperity

High debt and low growth are not a good signal for FDI. Are we ready with comparatively better and strong institutions, strong macroeconomic outcomes, comparatively better human capital, better position in terms of trade openness and non-informality, better investment climate, healthy growth and rising labour productivity? Answers to all those questions should be ready not with what we are going to do but with what we have done so far. We need high-growth sectors to channel FDI not to politically important low-growth sectors. We need to move on to a growth trajectory sooner than later.

We cannot rely on the undiversified, constantly fragmenting, low-capital incentive, low-knowledge incentive and low-productive rural agricultural holding to boost economic growth. They are subjected to a productive and reproductive squeeze caused by the rising cost of living. They look powerless but most powerful in choosing or defeating political parties as the majority of voters represents the agricultural sector. In this respect, it is the fear rather than the power that political authorities are forced to divert State resources to satisfy rural agricultural producers to stay in power. Our economy in this respect is likely to shrink in a ‘low growth trap’ with declining purchasing power and declining domestic demand. A radical change is needed to transform rural small agricultural holdings into diversified small mixed farming enterprises or units of productions with innovations and technological improvements. Addressing those problems depends on strong political commitments not to craft interventions for politics but to building a precious and self-sustained modern agricultural enterprise brick by brick.

We are in a highly complex, uncertain and unpredictable new era of global economic slowdown and are vulnerable to conflicting trade relations and geopolitical tensions. Hence, our political authority representatives must prepare better than before to build strong international relations and negotiation skills. They need to regularly update knowledge related to technological and educational transformation and enhance competencies towards more economically rationalised high growth sectors development. In contrast, destructive political confrontation has become so intense that it undermines constructive policy debates, with political parties focusing more on gaining and maintaining power. In this process, political differences grow more intensely and are increasingly detrimental to the working of the State. We need political stability to facilitate economic stability and build the county’s reputation externally. Changing the political approach from ‘political populism’ to ‘authoritarian populism’ will lead to political instability rather than to stability. Our small Island cannot afford costly, wasteful and destructive political divisions, fragmentation and polarisation. We need justice more than arrogance, cooperation rather than division, respect than disgrace and we need a common ground within a diverse political setting for negotiation and collective efforts of all political leaders at national level to address urgent and most critical challenges to growth and prosperity.