Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Tuesday, 23 February 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

There is not much modern agriculture practiced in our region. Most of them basically have traditional experiences and skills on agriculture, even though they are very poor in producing goods and services using traditional practices in this business – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Overview

Overview

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought unprecedented disruption to our agriculture and food systems, increasing pressure on farmers and agribusinesses in our country and around the world. Historically, agriculture has been the most important sector of the Sri Lankan economy. Even though its contribution to the gross domestic product declined substantially during the past three decades (from 30% in 1970 to 7.3% in 2020), it is the most important source of employment for the majority of the Sri Lankan workforce.

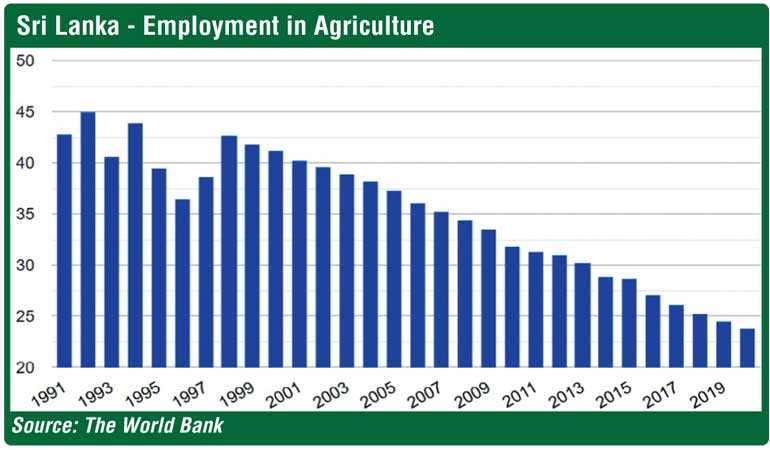

Nationally, approximately 2,140,000 persons or 25.5% of the total employed population are engaged in agriculture, inclusive of forestry and fishery. However, in the rural areas, agriculture is of even greater importance as over half of the workforce in rural areas is employed in agriculture. Nationally, of those employed in agriculture, about 1.3 million (65%) are also engaged in activities other than crop production. However, the sector has been undergoing many changes over the decades. Climate change, new policy changes, globalisation, technological change, competitiveness and many other daily changes are causing many challenges and developments. Beyond that, many measures are being taken by the Government from time to time.

The rural and estate sectors are home to 92% of the poor in the country. However, despite the dominance of agriculture-based livelihoods, the non-agricultural sector is the main source of employment in rural areas. Although Sri Lanka is a fertile tropical land with the potential for cultivation and processing of a variety of crops, issues such as productivity and profitability hamper the growth of the agricultural sector. There has been low adoption of mechanisation in farming. The lack of private investment in agriculture due to uncertain policies limits the expansion of the sector.

While agriculture’s share in Sri Lanka’s economy has progressively declined to less than 7.3% due to the high growth rates of the industrial and services sectors, the sector’s importance in Sri Lanka’s economic and the apparel and textile industry contributes 6% to Sri Lanka’s GDP while accounting for 40% of the country’s total exports.

In the subsistence sector, rice is the main crop and farming rice is the most important economic activity for the majority of the people living in rural areas. During the last five decades the rice sector grew rapidly. To guarantee a productive, competitive, diversified and sustainable agricultural sector will need to emerge at an accelerated Sri Lanka’s agriculture sector has also so far been affected by the COVID-19 outbreak, just like all other economic sectors. Even though the sector is only loosely integrated with global supply chains. From the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government adopted timely measures to minimise the impact on agriculture.

Challenges

This pandemic is unprecedented, causing tremendous uncertainty and hardship across the country — not only on the public health front but also in terms of people’s social and economic wellbeing, their access to food and nutrition. What makes this situation so challenging is the enigma of how unpredictable it is. While the crisis is slowing down in some countries, it is resurging or continuing in others. Restrictions on movement, quarantines, trade barriers and shipping delays have disrupted food supply chains, trade and logistics, with food supply chains in developing countries disproportionately affected.

The agricultural sector, which once contributed to more than half of Sri Lanka’s GDP, is now facing a number of challenges. Due to this pandemic and other various problems, the estimated 2.1 million agricultural households are at a risk of losing their livelihoods despite various measures taken by the Government to safeguard agricultural supply chains.

Ineffective labour force

Around 25.5% of the population in Sri Lanka engage in agriculture, though the sector’s contribution to GDP is as low as 7.3% (2020 data). Industrial work contributes 27% to GDP; in effect, an industrial worker is four times as productive as someone working in agriculture. Services sector workers are also around four times more productive.

Rice is the main food crop with (40%) grown in Sri Lanka followed by the plantation crop sector (38%), comprised mainly of tea, rubber and coconut. The sector has been affected by low productivity, water and land use inefficiency and high post-harvest losses for a long time. The picture below clearly shows the continuing decline in the contribution of labour force of this sector.

Dependence on traditional agriculture

There is not much modern agriculture practiced in our region. Most of them basically have traditional experiences and skills on agriculture, even though they are very poor in producing goods and services using traditional practices in this business. Modern agriculture is being shaped by many of the same technologies transforming other industries. This is most apparent at either end of the agribusiness supply chain; seed producers and supermarkets where technology has made a huge difference.

Climate change

The Sri Lankan agricultural sector has also been experiencing the effects of changing climate and natural disasters and being the 2nd in the Global Climate Risk Index. This has, however, given an incentive for the farmers to shift towards climate smart agriculture. In line with this emerging trend, Government adopted many measures to modernise the agricultural sector with support from donor agencies.

Lack of market information

During the last 50 years, agriculture has become large scale, intensive and specialised, in the rich world. Argentina, Brazil and China have led developing countries in creating globally competitive agriculture. However, countries like Sri Lanka can’t match Brazil or China’s gains as it lacks an obvious resource, land. Most of Sri Lanka’s farms are smallholder controlled and less than two hectares (4.9 acres). Lack of market information and logistical difficulties prevent smallholders from accessing markets efficiently. If the product is to be exported, the logistics and financing requirements are beyond their capability.

Will increasing yields by half of Sri Lanka’s highland tea gardens and rice paddies require a doubling of inputs? Not really. It will undoubtedly require more capital and labour. However, the land, one of the most significant inputs, will not change.

Policy level challenge

The biggest impediment to agricultural development is not at policy level; the Government often comes up with good policies, the flaw is at implementation level. Another impediment faced by the agricultural sector is the weak functioning of our agricultural research and development programs. It appears, that many research programs are confined to laboratories and do not adequately reach the farm lands.

The way forward

Sri Lanka needs industrial structural transformation that all countries experience as they develop and shift towards manufacturing and services. The solution for Sri Lanka, as for all other countries, is to make the needed investments so that agricultural production, foreign exchange earnings and farm incomes do not collapse as a consequence of the loss of labour in the process of economic structural transformation. Meeting the challenges will mean adopting technology to increase labour productivity, improving farm-market linkages, investing in value chains and also generating off-farm employment to absorb excess labour in the rural areas.

In order to meet the climatic challenges new irrigation systems, pest control, maintenance as well as harvesting could be digitalised. Furthermore, post harvesting must be a serious concern for value addition even with obtained agricultural wastes.

The new technologies can be introduced to agriculture to enhance productivity, efficient land use and reduce post harvesting losses. In addition, bridging the information gap and improving the efficiency of risk management tools and procedures using ICTs to reduce the individual risks of agriculture sector stakeholders will be added value for their entire products.

We must encourage universities and academia to strengthen research and capability to develop applications and services. So, the relevant agencies must facilitate availability of timely data and platforms for development and delivery of these services.

Generally, the solution lies in the restructuring of the entire agricultural system, including education, it is time the Government seriously considered that its agriculture policies should change from farming-centric to farmer-centric. It makes a big difference to farmers. Being relevant, we must improve the awareness, education and skills of farmers, extension workers, livestock herders and other sector end-users by creating and disseminating credible agricultural knowledge remotely.

We must reduce the demand-supply gap, and enhance outreach and profitability of Sri Lankan products and services through vibrant e-agriculture market places and efficient logistics. To reach the outcome of this sector is to create tools for analysing and linking nationwide demand and supply of agricultural produce. Unfortunately, with the current situation, achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, especially zero hunger and poverty, will be even harder now. We need to redouble our efforts to build sustainable agriculture food systems that are better able to withstand crises and shocks.