Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Friday, 14 July 2023 00:13 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

Sri Lanka’s attempt to come out of its worst economic crisis since independence with reforms under the four-year Extended Fund Faculty (EFF) program has entered a new phase with the announcement on 29 June of the domestic debt-restricting plan.

Sri Lanka’s attempt to come out of its worst economic crisis since independence with reforms under the four-year Extended Fund Faculty (EFF) program has entered a new phase with the announcement on 29 June of the domestic debt-restricting plan.

Sri Lanka entered the EFF program with a stock of public debt of $ 82 billion (128% of GDP), with domestic and foreign debt accounting for approximately equal shares. At the time, the Government’s annual interest payments on debt was over 65% of total revenue and domestic debt accounted for over two thirds of this interest burden. A group of international sovereign bond (ISB) holders, who account for about 60% of Lanka’s ISBs, had already informed the IMF that they were ready for restructuring debt subject to restructuring domestic debt in a manner compatible with debt sustainability and financial stability (Reuters 2023a).

This ground reality, coupled with the previous global experience of debt restricting in other debt-distressed countries (Das et al 2012, Grigorian 2023), clearly indicated that ‘twin restructuring’ of Sri Lanka’s external and domestic debt will be part of the EFF program. However, surprisingly, the program that was presented initially focused solely on the foreign currency debt, giving the false and misleading impression to the Sri Lankan public that there would be no restructuring of domestic debt as part of the overall EFF programs. The pipe dream, highly published in Sri Lankan policy circles at the time by the Sri Lankan authorities was that foreign debt restructuring and macroeconomic adjustment alone would achieve debt sustainability without an upfront attempt to domestic debt restructuring.

Key milestone

It was only after implementation of the program began in April 2023 that the restructuring of domestic debt was brought as an essential prerequisite for proceeding further. The IMF emphasised that progress in debt restructuring was a key milestone in the first performance review under the EFF for releasing the second tranche of the loan in September/October. At the same time, the international bondholders who hold $ 12.5 billion of Sri Lankan ISB had demanded equal treatment of foreign and domestic creditors for their participation in debt restructuring. Consequently, the Government came with a domestic debt restricting plan (evasively labelled ‘domestic debt optimisation (DDO)’ plan) as an appendage to the original EFF. Apparently, the designing of the DDO was preceded by a meeting of the international bondholders and Sri Lankan Government officials together with their financial advisors held in Washington DC in the second week of April 2023 (Reuters 2023b).

The DDO covers public debts of three broad categories: treasury bills (short-term government debt obligations backed by the Treasury) held by the Central Bank ($ 7.1 b); treasury bonds (medium- to long-term debt securities) held by superannuation funds ($ 8.8 b); and USD denomination Sri Lanka Development Bonds (SLDBs) and USD loans of commercial bank ($ 1.4). These three categories account for about 39% of total domestic public debt. In each case, the proposed restructuring involves lengthening of maturities of old debt and lowering interest rates without any ‘haircut’ (reduction in the face value of old debt).

Central Bank holdings of treasury bills are to be converted into bonds maturing between 2029 and 2038, with step-down interest rates of 12.4% until 2024, 7.5% until 2026 and 5.0% until maturity. Treasury bonds held by superannuation funds are to be exchanged for longer maturity bonds (2027 to 2038), with an interest structure of 12% until 2025 and 9% thereafter until maturity. SLDB holders are offered three options: two options to exchange holdings for new USD-instruments (‘USD options’) and exchanging holdings for new local currency instruments (‘LKR option’).

The first USD option is a nominal haircut of 30%, with repayment in six years starting in 2024 at 4.0% interest rate coupled with settlement of past due interest and interest accrued up to the settlement date in LKR. The second USD option involves maturity extension to 15 years at a 1.5% fixed interest rate, with a 9-year grace period and no haircut. The LKR option entails exchanging holdings for local currency denominated instruments at no haircut with 10-year (2033) with first amortisation in 2024 at a variable interest rate of the Central Bank policy rate + 1%. The two ‘USD options’ are specifically designed to meet the ‘equal treatment’ demand of ISB holders and therefore they are equally applicable to them and SLDB holders. The first of the two USD options is obviously the most attractive to ISB holders; the second option looks like ‘window dressing’ meant merely to give the impression of another option.

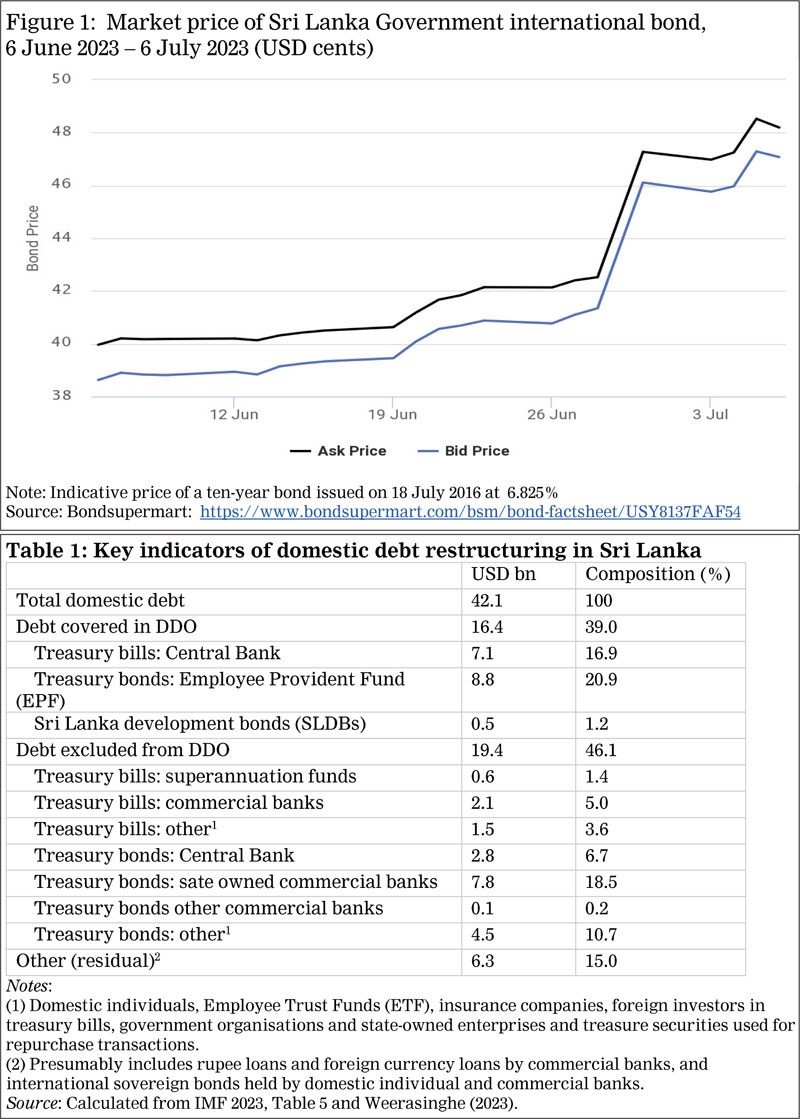

The 30% haircut and interest rate adjustment offered to the international bond holders would amount to about 35% debt relief on ISBs. This deal, which presumably reflects the Government’s desire to quicken progress in debt restructuring, is heavily in favour of the ISB holders compared to what was initially presented in the EFF program. In the EFF program, 14.1 billion of the projected external financing gap ($ 25 billion) of the program financing was expected to come from debt reliefs from bilateral creditors and ISB holders. Total external debts subject to restructuring (that is, total debt net of debt to multilateral creditors) was $ 28 billion. The expected debt relief from ISB holders was, therefore, around 50% (assuming equal burden sharing by the two groups of creditors). Interestingly, reflecting the ISB holders’ jubilant response to the new deal, which was obviously much better than they had expected, the market price of Sri Lankan ISBs has risen sharply following the announcement of the DDO on 29 June. (See Figure 1.)

Original external financial gap projection in EFF program needs significant revision

The significant difference between the originally anticipated rate of debt relief on ISBs (50%) and the new deal (35%) implies that the original external financial gap projection in the EFF program needs significant revision. The highly favourable deal offered to the ISB holders could also strengthen the hands of bilateral creditors, in particular China, which accounts for the bulk of Sri Lanka’s debt ($ 7.3 billion out of $ 11.5 billion), in forthcoming debt restructuring negotiations. Why ISB holders should be treated in the same way as bilateral donors will require some explanation as ISB holders debts are at much higher interest rates and for much lower durations.

A unique feature of the DDO proposal, compared to domestic debt restructuring programs in other countries (Das et al 2012), is its partial coverage (Table 1). About 61% of total domestic debt is left out of the program coverage. Government domestic debt in the form of treasury bills and treasury bonds held by the domestic commercial banks (which account for about 5% and 18.7%, respectively, of total domestic public debt) are excluded from the coverage. Also excluded are debts to the lump-sum group of ‘other creditors’ (‘other’ treasury bill and treasury bond holders and the residual category) who together account for 29% of domestic public debt. The distribution of creditors within this group is presumably tilted towards higher income brackets compared to the contributors to the EPF.

Treasury bills held by commercial banks, unless they account for a significant share in Government debt, are rarely included in debt restructuring. This exclusion is normally done to keep open a critical source of short-term credit for the Government and avoid adversely impacting on the operation of interbank transactions which use treasury bills (short term Government papers) as collaterals. However, the exclusion of treasury bonds held by the banks is rather unusual. Interestingly, Fitch Ratings, a major credit rating agency, had anticipated treasury bonds to be included in restructuring (Fitch Rating 2023).

‘Captive’ institutions

Of course, putting the entire burden of domestic debt restructuring on ‘captive’ institutions—the Central Bank and the EPF managed by the monetary board of the Central Bank—is an easy option for the Government. However, the favoured treatment to commercial banks and domestic government security holders compared to the EPF, coupled with the better than expected deal offered to the ISB holders, is clearly an inequitable distribution of the burden of debt restructuring among creditors. The savings of salary owners in the EPF is meant to provide a reasonable post-retirement income. Their current real incomes have already been cut by high inflation and higher taxes; now the DDO cuts their future incomes as well.

The authorities have given a number of justifications for the exclusion of banking sectors from DDO. These include the higher incidence of the recent increased corporate and value added taxes on banks compared to other corporations, weak balance sheets of the banks as reflected in non-performing loan ratio of 13% and a sizeable share of impaired loans in bank balance sheets, and the possible negative impact of ISB and SLDB restructuring on bank balance sheets.

However, ‘ring fencing’ of the banking system within the debt-restructuring programme is a mere palliative for the deep-tooted balance-sheet fragility of the banking system. Much needed capital enhancement of the banking system and cushioning it against the adverse impact of the other elements of the stabilisation policy package need to be systematically addressed under the so-called ‘forth pillar’ of the EFF programme: ‘policies to safeguard financial sector stability’ (IMF 2023, p. 2). This is vital to ensure the ability of the banking system to participate effectively in the recovery process.

The authorities claim that the bank deposit holders are safe under the proposed DDO program. However, this assurance needs to be qualified in view of the precarious state of the banks’ balance sheets, as emphasised by the Central Bank Governor to justify exclusion of banks from the debt restructuring process (previous paragraph). Moreover, as the Governor has himself pointed out, the conversion of holding of treasury bills into treasury bonds at lower interest rates under the DDO would significantly erode the capital buffers of the Central Bank (Weerasinghe 2023). Therefore, unless recapitalised, the Central Bank would not have capacity, credibility and independence to rescue the deposit-taking banks in the event of a deposit run.

Contrary to the initial false expectation of the Government and the designers of the EFF program, restructuring of domestic debt is necessary for Sri Lanka to come out of the crisis. However, it is important to undertake debt restructuring across the board with carefully designed contingent plans to preserve and foster confidence in the banking system. The proposed partial DDO is highly inequitable. It passes on most of the burden of adjustment onto the salary owners and ordinary people, while sparing the banking sector and treating international creditors and individual domestic creditors very generously. This is not a recipe for social and political harmony, pre-requites for recovery and sustainable long-term growth.

References:

Das, Mr Udaibir S., Mr Michael G. Papaioannou, and Christoph Trebesch. “Sovereign debt restructurings 1950-2010: Literature survey, data, and stylized facts.” (2012).

Fitch Rating (2023), Sri Lanka’s domestic debt plan’, 04 July https://www.fitchratings.com/research/banks/sri-lankas-domestic-debt-plan-significant-step-for-resolving-bank-uncertainty-04-07-2023

Grigorian, David A. (2023), ‘Restructuring domestic sovereign debt: Fiscal savings and financial stability considerations.’, Washington DC: International Monetary Fund. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/4139945/restructuring-domestic-sovereign-debt/4948204/

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2023), Sri Lanka: Request for an Extended Agreement under the Extended Fund Faculty- Press Release, Staff report, and Statement by the Executive Board for Sri Lanka, Country report 23/1 file:///C:/Users/u9502028/Dropbox/Sri%20Lanka/Debt%20trap/EFF%20Sri%20Lanak%20country%20report%201LKAEA2023001.pdf

Reuters (2023), ‘Exclusive: Sri Lanka’s bondholders send draft rework proposals to government’, 16 April. https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/sri-lankas-bondholders-sent-debt-rework-proposal-government-sources-2023-04-14/

Reuters (2023a) Sri Lanka bondholders ready for debt restructuring, 3 February. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/sri-lanka-bondholders-ready-debt-restructuring-talks-2023-02-03/

Weerasinghe, Nandalal (2023), ‘Debt restructuring in Sri Lanka’ (presentation to the Cabinet), 28 June, Central Bank of Sri Lanka. https://counterpoint.lk/governor-central-bank-makes-presentation-cabinet-domestic-debt-optimization-2/

(The writer is Emeritus Professor of Economics, Australian National University, and Visiting Honorary Professor, University of Peradeniya. He gratefully acknowledges incisive comments and suggestions made on the draft paper by Professor Sisira Jayasuriya, Monash University.)