Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 20 September 2025 00:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Despite their differences, these three movements reveal striking commonalities

Taken together, these uprisings demonstrate both the resilience and the fragility of democracy in South Asia. They remind us that popular sovereignty is not exercised only at the ballot box but also in the streets when institutions falter. Repression corrodes legitimacy, while timely engagement can transform dissent into democratic renewal. For democracies everywhere, the lesson is clear: listen to citizens before the street becomes the only forum for dialogue

Introduction

Introduction

South Asia is living through an era of popular uprisings that has reshaped the political vocabulary of the region. In Colombo, Dhaka and Kathmandu, ordinary citizens—many of them strikingly young—have turned public squares into stages for democratic confrontation. These movements differ in their national contexts and immediate triggers, yet together they illuminate how people power can both rescue and test democratic institutions.

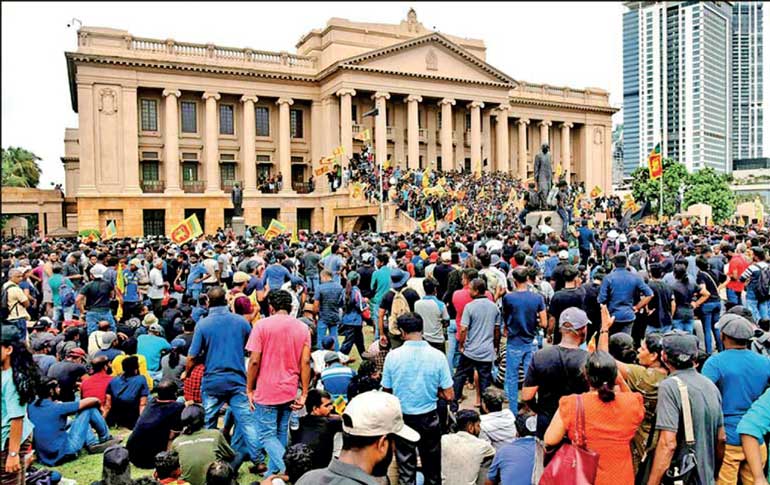

Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya

Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya of 2022 remains the most dramatic of the three. Confronted with an unprecedented economic collapse, spiralling inflation and crippling shortages of fuel and medicine, citizens of every ethnicity converged on Colombo’s Galle Face Green. Their demand was simple but revolutionary: an end to executive overreach and the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Despite occasional provocations and isolated violence, the protests were largely peaceful, disciplined and inclusive.

After Rajapaksa fled the country in July 2022, Parliament elected Ranil Wickremesinghe, who had previously served as prime minister six times, as president to serve out the remainder of the term. His selection, achieved through a parliamentary vote rather than a direct election, provided a measure of constitutional continuity at a moment of profound uncertainty and helped stabilise the government until fresh elections could be held. Parliament subsequently adopted the Twenty-First Amendment to the Constitution, which restored key checks on presidential power and revived independent oversight commissions.

Bangladesh’s protest wave

Bangladesh’s protest movement of 2024–25 grew from a different soil. It was not national bankruptcy but deep disquiet over electoral manipulation, rising costs of living and shrinking space for the press that brought students, garment-sector workers and middle-class professionals onto the streets. They demanded a neutral caretaker government and a genuinely independent election commission. Sit-ins and citywide strikes paralysed Dhaka, and encrypted messaging allowed demonstrators to stay a step ahead of police action.

In a parallel political shift, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus, internationally known for his pioneering work in microfinance, was invited by a broad coalition of civic leaders to act as chief adviser to an interim caretaker administration aimed at restoring confidence in the electoral process. His acceptance signalled an effort to pair political reform with economic credibility, and protest leaders hailed the move as evidence that the demand for clean governance was beginning to shape the country’s formal politics. Yet the state’s security response remained heavy-handed: riot police dispersed crowds, mass arrests followed, and temporary internet blackouts became a recurring tactic. Dialogue has been sporadic and the reforms sought remain incomplete.

Nepal’s civic agitations and interim leadership

Nepal’s agitation, while long-building, erupted dramatically in September 2025. Months of frustration over corruption, stalled federal reforms and youth unemployment had drawn citizens to the streets across the country. On 11 September, protesters forced their way into the grounds of the Federal Parliament in Kathmandu, smashing windows and setting fire to parked vehicles before police regained control with tear gas and water cannons. Dozens of protesters and security personnel were injured in the confrontation, which marked the most violent day of Nepal’s current movement.

The following day, after frantic negotiations among political parties, protest leaders and President Ram Chandra Paudel, former Supreme Court Chief Justice Sushila Karki was sworn in as Nepal’s first woman interim Prime Minister. Widely respected for her integrity and her earlier anti-corruption rulings, Karki has been tasked with steering the country toward early parliamentary elections and initiating a renewed dialogue on constitutional reforms. Protest groups have cautiously welcomed her appointment as a necessary first step, even as they continue to demand deeper institutional change and accountability for the violence that preceded her rise.

Shared characteristics

Despite their differences, these three movements reveal striking commonalities. Chief among them is the centrality of youth. South Asia is the world’s youngest region, with more than half its population under 35, and it is this generation that has driven the uprisings. University students and first-time voters provided the organisational muscle and digital sophistication that kept protests decentralised and resilient. They livestreamed events, coordinated supplies and countered misinformation, all while displaying a marked indifference to the old dynastic parties. Their independence lent authenticity and widened the appeal of each movement, even as it sometimes made negotiation difficult when no single leader could claim to speak for the crowd.

Economic distress provided another shared catalyst. In Sri Lanka, the crisis was existential, with the state literally running out of foreign exchange. In Bangladesh, inflation and job insecurity gave otherwise abstract calls for electoral reform a visceral urgency. In Nepal, stagnant growth and chronic corruption fed a slower but equally potent sense of grievance. Across the region, material hardship turned constitutional debate into a matter of daily survival.

Perhaps the most striking similarity is the instinct for non-violence. Candle-light vigils, communal kitchens and volunteer-run medical posts became the public face of protest from Colombo to Kathmandu. Even when individual incidents of vandalism occurred—as they did in all three countries—the dominant ethos remained peaceful, a fact that garnered international sympathy and moral authority. Yet Nepal’s storming of parliament is a reminder that when governments delay or dismiss dialogue, even largely peaceful movements can tip into confrontation.

Violence and state response

The temptation toward violence lingers as a warning across the region. In Sri Lanka a few angry groups stormed the presidential residence and torched homes of politicians. In Bangladesh buses were burned and police stations attacked, prompting harsh reprisals including rubber bullets and mass detentions. Nepal’s parliamentary breach and the injuries it caused underscore how quickly protest can escalate when frustration deepens. Governments have used these incidents to justify crackdowns, illustrating how even limited violence can erode public support and provide a convenient excuse for repression.

Sri Lanka after the Aragalaya

Where the uprisings diverge most sharply is in their outcomes. Sri Lanka stands out as the clearest example of peaceful protest leading to systemic change. After the Aragalaya, the country moved from sovereign default to a surprisingly swift recovery. Inflation, which had exceeded 70%, fell to single digits. Foreign reserves climbed beyond $ 6 billion, and gross domestic product grew by about 5% in 2024 after two years of contraction. Parliament passed the 21st Amendment to the Constitution, restoring key checks on presidential power and limiting the head of state’s ability to dissolve Parliament or dismiss the prime minister.

In the 2024 General election the left-leaning National People’s Power coalition captured a historic super-majority, seating more than one hundred and fifty first-time members of parliament and a record number of women. It appears that the current Government is committed to anti-corruption drives, welfare expansion and land redistribution, even as they adhere to the fiscal discipline demanded by the International Monetary Fund. This combination of constitutional reform, generational turnover and early economic rebound illustrates how a largely peaceful uprising can catalyse deep structural change.

Cautionary lessons from Bangladesh and Nepal

Bangladesh and Nepal tell more cautionary tales. In Dhaka the government has not yielded to the protesters’ central demands for a neutral caretaker authority or comprehensive electoral reform. Repression has hardened, dialogue has stalled and the possibility of gradual democratic backsliding remains real. Nepal’s interim government under Sushila Karki offers a potential opening, yet it remains to be seen whether it will translate the energy of the streets into lasting constitutional and economic reforms. These contrasting trajectories show that people power, while necessary, is not sufficient: it must be met by institutions capable of translating protest into policy.

Youth as democratic engine

The youth factor runs like a bright thread through these stories. Young organisers in each country mastered the tools of the digital age to mobilise support and to counter disinformation. They also expressed a clear impatience with politics as usual, demanding not only regime change but job creation, climate action and transparent governance. Their involvement presents both an opportunity and a challenge. Governments that harness this energy through inclusive dialogue can convert dissent into constructive nation-building. Those that dismiss it risk alienating the very generation on whom their countries’ future depends.

Lessons for democracies

Taken together, these uprisings demonstrate both the resilience and the fragility of democracy in South Asia. They remind us that popular sovereignty is not exercised only at the ballot box but also in the streets when institutions falter. Repression corrodes legitimacy, while timely engagement can transform dissent into democratic renewal. For democracies everywhere, the lesson is clear: listen to citizens before the street becomes the only forum for dialogue.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya, Bangladesh’s protest wave and Nepal’s civic agitations share a family resemblance—youth-driven, economically charged and morally anchored in non-violence—yet differ sharply in trigger, intensity and outcome. Their experiences underscore a universal democratic truth: peaceful protest can be a powerful instrument of reform, but only where political institutions are willing to translate moral pressure into lasting change.

References:

“Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya: Anatomy of a Protest,” The Hindu, August 2022.

“Sri Lanka’s Parliament Elects Ranil Wickremesinghe President,” Reuters, July 20, 2022.

International Crisis Group, After the Aragalaya: Sri Lanka’s Transition, 2023.

“Bangladesh Youth Lead Election Integrity Protests,” Dhaka Tribune, July 2025.

“Caretaker Government Taps Muhammad Yunus as Chief Adviser,” Dhaka Tribune, September 2025.

“Protesters Storm Nepal’s Parliament; Sushila Karki Named Interim Prime Minister,” Kathmandu Post / Reuters, September 12, 2025.

IMF Country Report No. 25/42, Sri Lanka: Third Review under the Extended Fund Facility, February 2025.

“Sri Lanka’s Economy Grew 5% in 2024, Rebounding from Crisis,” Reuters, March 2025.

(The writer is former Sri Lankan Ambassador to EU, Belgium, Turkey and Saudi Arabia.)