Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Thursday, 9 October 2025 05:31 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Dodges BRICS, SCO, Beijing parade; meets Japan’s Emperor

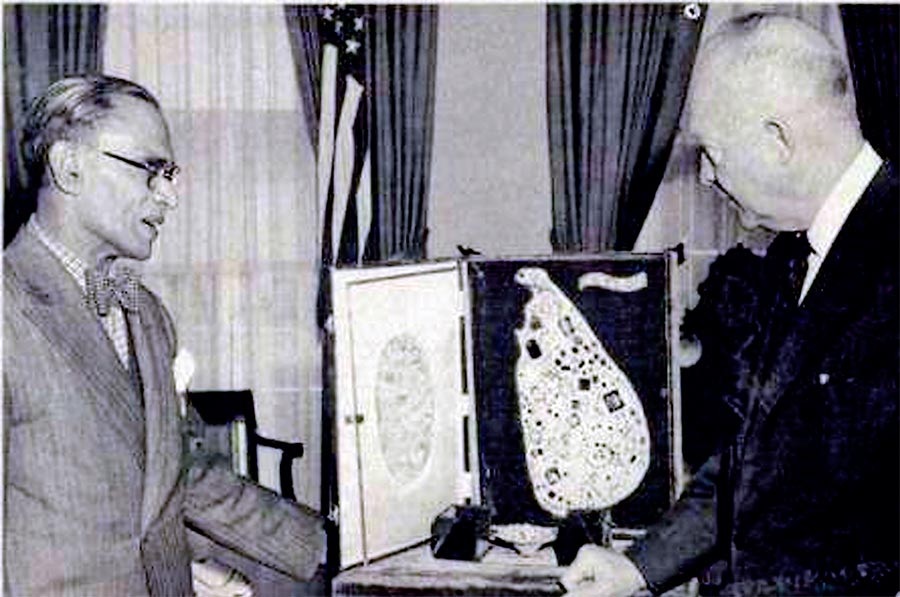

SWRD Bandaranaike, first Ceylonese head of government to address UNGA, Nov 1956

SWRD with President Eisenhower at the White House

The JVP-NPP’s Goebbelsian lie of a 76-year-old, post-Independence ‘curse’ and a Sri Lankan ‘renaissance’ under AKD, collapses in the domain of foreign policy and international relations.

The JVP-NPP’s Goebbelsian lie of a 76-year-old, post-Independence ‘curse’ and a Sri Lankan ‘renaissance’ under AKD, collapses in the domain of foreign policy and international relations.

Apologists for President Anura Dissanayake’s surreal foreign policy, a major deviation from the mainstream of Sri Lanka’s external relations tradition, view that policy through a pair of rose-tinted lenses:

Economic determinism: the country and Anura are caught in structural constraints, chiefly the IMF program and debt repayment obligations.

Economic determinism: the country and Anura are caught in structural constraints, chiefly the IMF program and debt repayment obligations.

Hedging: Anura is engaged in the most realistic option under the circumstances.

Hedging: Anura is engaged in the most realistic option under the circumstances.

Both lenses are cracked. Firstly, Anura did not try to secure his new administration and the country any countervailing capacity (he avoided BRICS Plus) or wiggle-room for renegotiation. The ‘structural constraints’ are tighter because of his choice of complete conformity, continuity and compliance. Secondly, ‘hedging’ would be making the Tianjin SCO summit and the Tokyo trip, not avoiding the first while doing the second.

With episodes of erroneous exceptions, Sri Lanka’s foreign policy practice has been actively participatory and its discourse reformist, seeking to raise our profile and secure space while collectively striving to reform the international system so as to gain a better, fairer deal for countries like ours.

AKD has abandoned that ‘great tradition’. Connect the dots and you’ll see that his preferential option is to inhabit a triangular cage: India-Japan-Israel.

For the first time since 1948, foreign policy isn’t rooted in a calculus of the interests of the Sri Lankan State by its elected leadership, but is the product of the interface of initiatives by a few top corporates and interests of the ruling JVP-NPP. This new oligarchy determines our foreign relations.

|

Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro makes impassioned speech at UNGA 2025

|

|

At UNGA, Chile’s President Gabriel Boric draws parallel between Gaza and Holocaust

|

|

Brazil’s President Lula, elder statesman of the world’s democratic left, tells UNGA sovereignty is non-negotiable

|

Internationalism of the intellect

Sri Lanka must understand the complex and fluid – ‘kaleidoscopic’ (Mervyn de Silva)— character of the changes taking place in the world system and order, so as to decide how this small but strategically located island must navigate so as to defend, manage and advance its national interests.

Our greatest foreign minister Lakshman Kadirgamar was well aware of this. In 2005, the last year of his life, he founded a journal of which he was the Editor-in-Chief, entitled International Relations in a Globalizing World (I was a member of the Editorial Board) precisely because he understood the need for a conceptual grasp of global affairs for the formulation of foreign policy.

Kadirgamar belonged to an elite with a tradition, namely the ‘internationalist’ generation of the post-Independence Ceylonese intelligentsia which among other things, established the prestigious, non-state, non-corporate Ceylon Institute of World Affairs (co-founded/re-founded in the 1960s by Maj-Gen Anton Muttucumaru and Mervyn de Silva).

What is most lacking in the current Sri Lankan discussion on world affairs is the analytical starting point of totality, i.e., beginning with a grasp of global or world-system dynamics and contemporary history. Instead, personal, partisan and parochial factors determine the interpretation of the global.

Hegemony vs. Multipolarity

Current history is characterised by the striving of the Western powers to maintain their hegemony in the world system and restore the unipolarity of the post-Cold War moment, at a time the world system and order are increasingly multipolar. The West strives to hold the East and South in check, while the US attempts to restore its dominance within the West and over the world order while dramatically reordering its own domestic social contract.

The West’s project is global counterreformation, even counterrevolution. It is a struggle between two tendencies i.e., US/Western hegemonism vs. global multipolarity, which point in two directions, i.e., return to West-centrism vs. evolution to multipolarity.

It is a contest between a conservative or reactionary project (however ideologically liberal many Western players may be) of the maintenance of the current extent of Western dominance or a rollback to post-Cold War unipolarity, and the revisionist/reformist project (however ideologically conservative the Eurasian players) of a multipolar and therefore more balanced, pluralist, democratic, world order.

Sri Lanka’s stance

Sri Lanka must have a clear sense of where its most fundamental interests lie, and base its way of being in the (dynamically evolving) world accordingly. While rooting ourselves firmly, we must also have our ‘heads on a swivel’, aware of everything that’s happening, spotting possible dangers, advantages and opportunities. Sri Lanka must have a firm ‘Grand strategic’ stance, while having flexible tactics.

What must that firm ‘Grand strategic’ stance be and derive from? It must be rooted in reality; the geopolitical and existential reality of who, what, where we are (as Mervyn de Silva insisted).

Sri Lanka is located in --belongs in –the Global South and therefore belongs to the Global South. Some of our politicians may have delusions to the contrary, but this is the ineluctable reality. Therefore, one of the axioms of our foreign policy must be to identify ourselves with the Global South and leverage the benefits of belonging to it.

Sri Lanka is located in Asia. Therefore, it must identify itself with Asia in particular and Eurasia in general.

A small island state, Sri Lanka should associate itself with the Global South and Eurasia, which contain the overwhelming majority of humanity as well as of the member states of the United Nations.

Covid-19 and Trump tariffs have shown us that supply chains can be blocked, external markets are elastic and therefore cannot determine our foreign policy.

Our foreign policy must reflect our identity and serve our long-term interests. We must stand with whom we share a broad identity, basic ideas and interests.

Though the foundational positioning of Sri Lanka must be within the Global South/Eurasia, we mustn’t perceive or project ourselves as ‘anti-West’ because we have something fundamental which we share with the West, and almost certainly more with the West than the East, while there is something fundamental we share with the East, and much more with the East than the West.

Ceylon/Sri Lanka is the oldest multiparty democracy in Afro-Asia. We fought two civil wars to protect and preserve that competitive, pluralist civilian democracy from the totalitarian left, and we won while never permitting dictatorship of the right or the military. In this, Ceylon/Sri Lanka has a better record than much of the Global South and parts of Europe.

No monolith, the West is also the home of dynamic progressive popular mobilisations in solidarity with just causes in the global South. While the diplomatic support for Palestine in the UN Security Council comes from the East, the mass protests against the genocide in Gaza come from the West and the South. The genocide case in the ICJ is from the South and North. A Palestinian state and peace with/for Iran will only come with a progressive Democrat in the White House. If Democratic Party candidate Zohran Mamdani, a committed ‘democratic socialist’, supporter of Palestine, child of parents from the global South, wins the New York mayoralty in November, it will shine a light for all progressives globally. Thus, Sri Lanka must never be anti-West. It must be internationalist.

Our fundamental interests and values intersect with both the West/North (pluralist democracy) and the East/South (independence, sovereignty). We need both sets of values. We cannot be aligned against the North/West or the South/East.

However weak the Nonaligned Movement today, the doctrine, the principles of Nonalignment remain the most suitable for Sri Lanka.

‘Committed to the hilt’

Sri Lanka must neither be ‘uncommitted’ nor ‘equidistant’. A year after the Bandung Conference (1955) and six years before the founding in Belgrade of the Nonaligned Movement (1961) with Ceylon’s Sirimavo Bandaranaike as a founding member, Prime Minister SWRD Bandaranaike addressed the 11th UN General Assembly and rejected the definition of “uncommitted nations” to describe those who subscribed to the Bandung principles. In a memorable turn of phrase, he roared that “we are committed to the hilt…to justice and freedom…”.

SWRD Bandaranaike was hardly equidistant when he faced a dilemma while addressing the UNGA: the twin crises in Egypt and Hungary. In Egypt it was the joint Israel-UK-France invasion and seizure of the Suez Canal after President Gamal Abdel Nasser had nationalised it. In Hungary it was the intervention by Soviet troops to suppress an anti-Soviet uprising in Hungary (perceived as fomented by the CIA) and prevent Hungary’s probable exit from the Warsaw Pact.

Bandaranaike spoke at far greater length and placed far heavier emphasis on the Suez crisis than on Hungary. Affirming Nasser’s right to nationalise the Suez Canal, he condemned the Israeli-Anglo-French invasion and seizure of the Canal. Objecting to a gradual, incremental withdrawal, he demanded that “Those forces must now be withdrawn without delay...now!”

Referring to “the Hungarian episode”, he supported that part of the Resolution calling for the withdrawal of Soviet troops but opposed the call for ‘free elections under UN auspices’ as a violation of national sovereignty.

“Are you surprised that we lay greater emphasis on Egypt than on Hungary?” asks SWRD Bandaranaike in his UNGA speech. He explains: “we of Asia…have undergone two or three hundred years of colonialism” and are more sensitive to anything that smacks of colonialism by ex-colonial powers.

To Bandaranaike’s rationale, I would add four reasons why we should privilege the North-South axis rather than the East-West axis, and should not tilt to the North against the South (as JR did catastrophically on the Falklands/Malvinas), or the West against the East.

i. As in Latin America and East Asia, political regimes such as right-wing dictatorships can be overthrown and democracy restored. But former Yugoslavia (where the NAM was founded) and several Arab and African countries prove that once a state is divided or disintegrated, it is almost never fully reunified, repaired, restored. On national independence, sovereignty, territorial unity and integrity, and opposition to secession, it is the global East and South that stand firm, while the West/North is sympathetic to or permits the activities of separatists (Canada and India’s Khalistanis, Sri Lanka’s Tigers).

ii. The vision of the Global South and Eurasia (BRICS, SCO etc.) of a multipolar world order, more equitable globalisation and multilateral diplomacy, is far more compatible with the interests of Sri Lanka than the US-led West’s hierarchical, hegemonistic vision of unipolarity (often coupled with unilateralism).

iii. It is far safer for a small state like Sri Lanka to prioritise its relationships with multilateral groupings containing the majority of the world’s populace and the world’s states, than to be dependent either upon the West/North which contains electorally consequential ethnic lobbies, or upon neighbours with ethnic kin-states/enclaves (e.g., Tamil Nadu) sympathetic towards secessionists, secessionism or annexation.

iv. The demographic weight of Eurasia and the Global South, taken together with the economic and military power of China and the nuclear power of Russia, bring balance into the world, shifting the needle towards ‘Global Equilibrium’ (Simon Bolivar, Jose Marti) which is in the interests of countries like Sri Lanka.

Pinnacle to puddle, eagle to poodle

Putting to shame those pundits who advocate a poodle-like foreign policy for Sri Lanka because of economics, it must be recalled that SWRD Bandaranaike, the first leader of this country to address the UNGA and the world through it, presented a passionate, self-confident vision not because Ceylon was big, rich or strong. “My country is a small one, a weak one, a poor one” he admitted honestly, but that hardly prevented him from declaring that Ceylon and the ex-colonial countries represented at the Bandung Conference were “committed to the hilt!”. Indeed, Ceylon’s reality was propellent not preventive for him to articulate the assertive foreign policy doctrine that he did.

Bandaranaike self-confidently conceptualised the challenges facing Ceylon in all their complexity, and did so while locating them in world history as it was unfolding.

“…At this epoch of newly gained freedom, we find ourselves faced with a dual problem. A problem within a problem. First, the problem of converting a colonial society, politically, socially and economically, into a free society—and the problem of effecting that conversion against a background of changing world conditions.

The world itself is in a state of change and flux today. The world is going through one of those rare occasions that happen in certain intervals of a changeover from one society to another, from one civilisation to another. We are living today in fact in a period of transition between two civilisations, the old and the new. At a period like this, all kinds of conflicts arise—ideological, national, economic, political; every kind of conflict. It has done so in the past. In the past they were settled by some nice little war here or there. Today we cannot afford the luxury of war, for we all know what it means. So, the task for us today is a far more difficult one than ever faced mankind—to effect this kind of transition to some form of stable human society and to do it amid a welter of conflict, with reasonable peace; with the avoidance of conflict that bursts out into war, for war is unthinkable today.

…We in Asia…we like to get something, some ideas, some principle from this side, some ideas from the other, until and unless a coherent form of society is built up that suits our own people, in the context of the changing world of today. That is why we do not range ourselves on the side of this power-bloc or that power-bloc…It is not sitting on the fence… It is a position that is inexorably cast upon us by the circumstances of the day…”

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ipy8NSGxhTQ)

Winding up his speech, SWRD Bandaranaike went on the offensive:

“…We are supposed to be uncommitted? I strongly object to that word, ‘uncommitted’! We are committed up to the hilt, believe me! We are committed to preserve decency of dealings between nations. We are committed to the cause of justice and freedom, as much as anyone...”

Unlike SWRD, AKD expressed no ‘commitment’ in his UNGA speech to any principle, concept, value, idea—still less one of a universal, transformational character. SWRD enunciated a foreign policy doctrine for Asian and ex-colonial countries in a new, complex global and historical situation. AKD preferred instead, a superficial and shallow presentation of Sri Lanka’s situation. He presented no perspective on current global changes as SWRD did, probably because he had none to offer.

The almost antinomian SWRD/AKD contrast isn’t sourced in Bandaranaike’s linguistic-oratorical advantage, because AKD addressed the UNGA in Sinhala. It is sourced in an asymmetry of intellect, a contradiction of consciousness.

One of the ‘Children of ‘56’ (Mervyn de Silva’s coinage, South Asian Review 1972) and leader of a self-professedly Marxist left party, President Anura Dissanayake’s UNGA speech was thin, hollow, vapid, instantly forgettable; incomparable and incompatible with the indelibly memorable, principled, courageous, visionary speech by SWRD Bandaranaike from the same rostrum.

JVP-NPP ideologues would sneer and splutter “that was a different era”, but AKD’s discourse also bore no resemblance whatsoever to that of Colombia’s Gustavo Petro, Chile’s Gabriel Boric and Brazil’s Lula at the UNGA this year.