Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Monday, 17 November 2025 00:22 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

President and Finance Minister

Anura Kumara Dissanayake

Treasury Secretary

Dr. Harshana Suriyapperuma

Senior Adviser to the President on Economic Affairs and Finance Duminda Hulangamuwa

The Value Added Tax (VAT) is imposed quarterly at the rate of 18% on four principal branches of business activity: manufacture, imports, trading (buying and selling), and services. Similarly, the Social Security Contribution Levy (SSCL) is also imposed quarterly at the rate of 2.5% on the very same branches of business.

The Value Added Tax (VAT) is imposed quarterly at the rate of 18% on four principal branches of business activity: manufacture, imports, trading (buying and selling), and services. Similarly, the Social Security Contribution Levy (SSCL) is also imposed quarterly at the rate of 2.5% on the very same branches of business.

It is difficult for any rational observer — except perhaps those in the political sphere — to comprehend the logic of maintaining such double taxation on the same business activities. The imposition of such dual taxes of similar nature on the same business turnover may serve short-term political convenience, but it does not reflect sound economic or fiscal policy wisdom.

Splitting what is essentially a single sales tax into two components, VAT and SSCL, may create the illusion of moderation, as each appears less burdensome when considered separately. However, this illusion cannot be sustained in the long run. Ultimately, the combined impact of these taxes increases the cost of doing business and triggers inflations, undermining efficiency of both tax administration and taxpayers.

Blind imitation of previous fiscal policies

It is a pity—if not a tragedy—that the NPP Government, which came to power with an overwhelming popular mandate to end a 76-year curse and open a new political chapter, now appears to be following the same outdated and illogical fiscal policies of its predecessors. It is not a secret that this duplicate sales tax of SSCL was introduced by the Ranil Wickremesinghe Government effective from 1 October 2022.

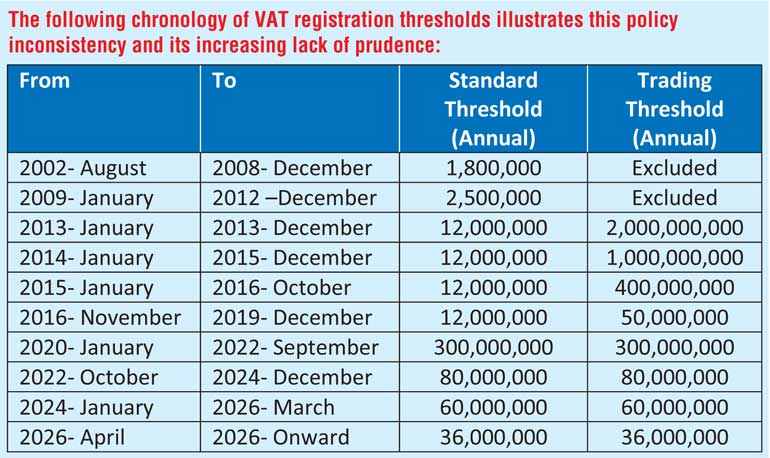

As the author highlighted in his earlier article “Keeping Trading Activity out of VAT: A Correction of a Bureaucratic Slip-up,” both the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and the Value Added Tax (VAT) were originally designed to exclude trading (buying and selling) activities from their scope. It is a matter of record that trading was later brought within the VAT net due to arbitrary bureaucratic outfox. However misguided, even that decision retained a semblance of prudence by maintaining a substantial disparity in the annual registration thresholds — Rs. 2,000 million for trading activities and Rs. 12 million for other non-trading activities.

As the author highlighted in his earlier article “Keeping Trading Activity out of VAT: A Correction of a Bureaucratic Slip-up,” both the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and the Value Added Tax (VAT) were originally designed to exclude trading (buying and selling) activities from their scope. It is a matter of record that trading was later brought within the VAT net due to arbitrary bureaucratic outfox. However misguided, even that decision retained a semblance of prudence by maintaining a substantial disparity in the annual registration thresholds — Rs. 2,000 million for trading activities and Rs. 12 million for other non-trading activities.

It was during President Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration that this distinction was removed, and a uniform threshold was introduced — Rs. 300 million for both trading and other activities. The Wickremesinghe Government continued this uniformity, revising the threshold first to Rs. 80 million and later to Rs. 60 million. Regrettably, the present President Anura Kumara Dissanayake Government seems to be treading the same path, maintaining an identical threshold of Rs. 36 million, effective from 1 April 2026, for both trading and non-trading activities.

Why should trading activity be removed from VAT and SSCL should be confined to trading?

It is regrettable that, too often, policymakers and legislators in Sri Lanka have not given due consideration to the original intent of a law before introducing new amendments. A more careful and objective examination of the purpose of the legislation, together with the implications of any proposed changes, could have helped avoid such unintended adverse consequences.

Prior to introduction of GST in 1998, Turnover Tax (TT) was in place at relatively lower rates and it was charged on all four main branches of a business. The TT mechanism had two primary defects in itself, namely cascading (tax on tax) effect and Administrative inefficiency.

Prior to introduction of GST in 1998, Turnover Tax (TT) was in place at relatively lower rates and it was charged on all four main branches of a business. The TT mechanism had two primary defects in itself, namely cascading (tax on tax) effect and Administrative inefficiency.

The introduction of GST/VAT solved the first problem by implementing a credit-invoice system that eliminated cascading. It solved the second by strategically limiting the VAT liability to manufacturers, importers, and service providers thereby focusing administrative efforts on fewer, larger taxpayers.

Charging VAT on trading Vs. MRP and lower margin

Subjecting traders to the same VAT burden as manufacturers and importers is inequitable and unjustified. Unlike these primary suppliers, traders operate at the end of the distribution chain with significantly lower margins. Furthermore, they are legally bound to sell goods at the Maximum Retail Price (MRP) as specified by the primary suppliers, non-compliance with which is a punishable offence.

In most cases, traders purchase their merchandise from suppliers who are not VAT-registered, which prevents them from claiming input tax credits. Even in situations where input credits are available, the payment of output VAT on trading activity becomes impractical when considered against the narrow trading margin and the statutory restriction imposed by the MRP.

Generally, traders who occupy the final stage of the distribution chain — unlike manufacturers and importers — operate with relatively low profit margins, typically within the 10% range. Consequently, net VAT revenue contributed by traders is often less than 2% of the turnover.

Imposition of dual taxes on the same business activities

Against this backdrop, the rationale behind imposing two identical taxes — VAT and SSCL — on the same four branches of business activity (manufacture, imports, trading, and services) is difficult to comprehend. It is needless to emphasise that levying two taxes of similar nature on the same base undermines one of the four cardinal principles of taxation: efficiency — both in administrative terms for the tax authorities and in compliance costs for taxpayers.

Against this backdrop, the rationale behind imposing two identical taxes — VAT and SSCL — on the same four branches of business activity (manufacture, imports, trading, and services) is difficult to comprehend. It is needless to emphasise that levying two taxes of similar nature on the same base undermines one of the four cardinal principles of taxation: efficiency — both in administrative terms for the tax authorities and in compliance costs for taxpayers.

If policymakers believe that duplicating taxes of the same character (VAT and SSCL) on these business activities will increase revenue, they are chasing an illusion. In reality, such duplication only compounds inefficiency, discourages business activity, and distorts the tax system’s integrity and simplicity.

Recommendations

It is disappointing that many professional bodies, trade chambers, and tax advisors — who are well-placed and ethically bound to speak up — have chosen to remain silent on this issue. Their voices matter, and their silence only deepens the policy vacuum. As a result, imprudent and adverse tax measures continue to prevail.

As a sovereign and independent nation, we must take responsibility for shaping our own destiny. It is neither reasonable nor prudent to attribute every instance of inaction or indecision to the IMF, as though it were our ultimate saviour. We should also bear in mind that institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, and similar organisations are supported by Western powers that naturally pursue their own strategic interests. These institutions engaged comfortably with previous corrupt political elites and regimes without raising a murmur. In other words, they too were complicit in creating the sorry and deplorable situation in which the country now finds itself.

I strongly believe that adopting the following recommendations will help the Government meet its revenue goals, improve the efficiency of tax administration, and most importantly, rebuild the trust and confidence of taxpayers and the public in our tax system.

Keep trading activity out of the VAT net

The time has come to return to the original spirit of the GST and VAT — to tax only where value is created, not where goods simply change hands.

The time has come to return to the original spirit of the GST and VAT — to tax only where value is created, not where goods simply change hands.

Trading (buying and selling) was initially kept out of the VAT system for good reason. It was a conscious, well-thought-out decision aimed at preventing inefficiencies and protecting small traders and consumers from unnecessary burdens.

Bringing traders into the VAT net later on (2013) was a mistake that distorted the system’s logic and increased costs across the board. Reversing that move is not a radical reform; it’s simply good sense — a restoration of fairness, simplicity, and economic logic.

Reduce the VAT Registration threshold to Rs. 12 million

Once trading activity is excluded from VAT, the annual threshold should be reduced to Rs. 12 million. This ensures that genuine value-adding suppliers — manufacturers, importers, and service providers — are covered under VAT.

A lower threshold will broaden the base sensibly, without dragging small traders into complex compliance obligations they were never meant to bear.

Remove primary suppliers from the SSCL

If manufacturers, importers, and service providers are already paying VAT, subjecting them to SSCL as well is both illogical and unfair. The SSCL, in practice, duplicates VAT on the same activity — a classic case of double taxation.

Primary suppliers should therefore be exempted from SSCL to eliminate overlap and confusion in the system.

Raise VAT from 18% to 20%

Once SSCL is removed from VAT-registered businesses, the small revenue gap that might arise can easily be bridged by increasing the VAT rate slightly — from 18% to 20%.

This minor adjustment would make the tax structure cleaner and more coherent, without adding any real burden on businesses or consumers.

Limit SSCL only to traders and non-VAT-Registered persons

The SSCL, at 2%, should be limited only to non-VAT-registered persons — mainly traders who buy and sell, and small-scale suppliers whose turnover is below the VAT threshold.

This targeted approach will make the system simpler, fairer, and easier to administer, while ensuring everyone contributes their fair share.

Conclusion

These proposals are not radical reforms — they are restorations of balance and common sense.

For too long, our tax system has been weighed down by duplication, inconsistency, and policy drift. By clearly separating VAT and SSCL, and by returning VAT to its original focus on value addition, Sri Lanka can create a more rational, transparent, and growth-friendly tax framework.

A fair tax system is not only about collecting revenue; it’s about building confidence — among taxpayers, investors, and the public at large. Implementing these measures will help rebuild that confidence and lay the foundation for a more stable and equitable fiscal future.

(The author is a Retired Deputy Commissioner General of the Inland Revenue Department and could be reached via email at [email protected])