Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Friday, 29 August 2025 01:17 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

|

| Former President Ranil Wickremesinghe | President Donald Trump |

The arrest of former President Ranil Wickremesinghe illustrates the structural tension in Sri Lanka’s constitutional design. In September 2023, while serving as president, Wickremesinghe traveled to Havana for the G77 Summit and to New York for the United Nations General Assembly. On his return journey, he stopped in the United Kingdom to attend a ceremony at the University of Wolverhampton, where his wife was awarded an honorary professorship. Investigators allege that state funds were improperly used to finance the UK leg of the trip. Wickremesinghe has denied wrongdoing, insisting that his wife personally covered her travel expenses.

The arrest of former President Ranil Wickremesinghe illustrates the structural tension in Sri Lanka’s constitutional design. In September 2023, while serving as president, Wickremesinghe traveled to Havana for the G77 Summit and to New York for the United Nations General Assembly. On his return journey, he stopped in the United Kingdom to attend a ceremony at the University of Wolverhampton, where his wife was awarded an honorary professorship. Investigators allege that state funds were improperly used to finance the UK leg of the trip. Wickremesinghe has denied wrongdoing, insisting that his wife personally covered her travel expenses.

On 22 August 2025, he was arrested by the Criminal Investigation Department and remanded in custody, making him the first former Sri Lankan head of state to be detained in this way. The Guardian reported that the charges may include penalties of up to twenty years’ imprisonment and fines of roughly Rs. 16.6 million (about $55,000). His arrest forms part of President Anura Kumara Disanayake’s anti-corruption campaign against senior public officials.

The difficulty raised by Wickremesinghe’s arrest is not only whether he misused public funds, but how such conduct should be classified. Was the London stopover part of his official duties as president, a symbolic or soft power diplomatic gesture undertaken in his capacity as Sri Lanka’s head of state, or a purely private engagement? The problem is that without such classifications, accountability after office becomes a matter of political discretion rather than constitutional principle. This is where the contrast with the United States is instructive. In Trump v. United States (2024), the Supreme Court sought to address this very problem by constructing a framework for classifying presidential acts. Whether one agrees with that ruling or not, it represents a systematic attempt to resolve the tension between presidential conduct, immunity, and accountability.

Trump v. United States (2024): Redefining Presidential Criminal Liability

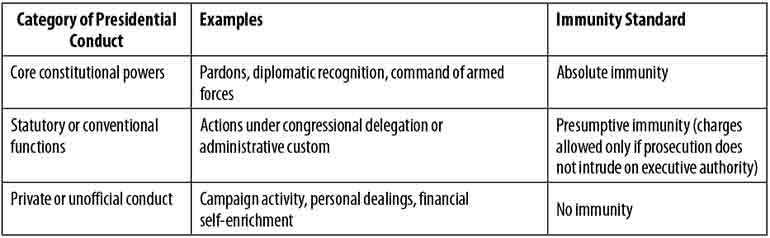

Table 1: Categories of Presidential Conduct and Immunity Standards in Trump v. United States (2024)

Trump v. United States (2024) required the Supreme Court to decide whether a former president could face criminal prosecution for actions taken while in office, and to what extent presidential immunity shields such conduct. The Court’s majority opinion did not begin with the substance of Donald Trump’s alleged conduct. Instead, it began with a structural question: how should presidential acts be classified? The decisive move in Trump v. United States was not the recognition of immunity as such but the decision to treat classification as the starting point. The Court held that liability is not contingent on whether an act is abusive or corrupt, but on its formal designation as belonging to the core constitutional powers, the outer perimeter of statutory or customary functions, or private conduct. Once classified, each category carries a corresponding rule of immunity.

The question of presidential immunity has become immediate, not theoretical. It will be contested in courtrooms and in politics, where partisan loyalties and high emotions will frame the terms. The challenge is to recall that the issue is not about Wickremesinghe as an individual. It is about the office of the presidency itself. A constitutional democracy must avoid both extremes: the misuse of presidential power while in office and the persecution of former presidents once power changes hands

The Court ruled that acts that fall within “the core” constitutional powers of the presidency are placed beyond scrutiny altogether. For example, presidential pardons, diplomatic recognition, and the command of armed forces are treated as domains covered by absolute immunity from criminal liability. Chief Justice Roberts’ argument that “the President may not be prosecuted for exercising his core constitutional powers” defines a new boundary of accountability. In this framework, the nature of the act is irrelevant and its classification as a core power alone determines immunity. Outside this core, the Court recognises an outer perimeter of acts performed under statutory authority or administrative customs. Here, immunity is presumptive rather than absolute. However, the structure remains protective of the Office of the President. The burden lies not on the president to justify immunity but on the prosecution to demonstrate that criminal process would not “risk distortion of the President’s decision-making and intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.” The presumption of immunity continues to hold, rendering liability the exception rather than the rule.

The Court’s third category is purely private conduct, which carries no immunity and remains fully subject to criminal law. Campaign activity, personal dealings, or financial self-enrichment are outside the protective circle. Yet even here, the evidentiary threshold imposed by the Court’s majority sharply narrows the prospect of prosecution. The majority further held that “official acts may not be admitted as evidence of motive or intent in prosecutions for unofficial acts.” This creates a barrier between the two categories, adding safeguards that shield official conduct while also insulating private conduct. Therefore, a president who uses official channels for personal gain may remain shielded, not because the conduct is benign, but because the evidentiary link has been severed by the ruling.

Roberts defended this structure as a constitutional necessity. Immunity, he argued, is not a personal privilege but an institutional safeguard. Without it, presidents would govern in the shadow of potential prosecution, and political disagreements could be recast as criminal charges. Therefore, he argued that the classificatory scheme stabilises the separation of powers by protecting the boldness and decisiveness the Framers expected of the executive.

The dissents saw the same framework as destabilising. Justice Sotomayor argued that the Court had created “a law-free zone around the President,” where the classification of an act as official was enough to shield even the most corrupt uses of power. She described the majority’s classification framework with absolute immunity for core powers, expansive immunity for all official acts, and an evidentiary prohibition on using such acts in prosecutions as “unnecessary,” “illogical,” and “nonsensical.” Under this rule, she cautioned, a president could order the assassination of a political rival, stage a coup to retain power, or accept bribes in exchange for pardons, and all would be immune. Sotomayor warned that the Court has now ensured that “all former Presidents will be cloaked in such immunity.” She ended with the warning that frames the case not as a dispute over legal doctrine but as a challenge to constitutional democracy itself: “With fear for our democracy, I dissent.”

Justice Jackson situated the danger in constitutional first principles. Immunity, she wrote, is not a defense within the law but an “exemption from the duties and liabilities imposed by law.” To grant it is to “create a privileged class free from liability for wrongs inflicted or injuries threatened.” In her account, the Court had resurrected the monarchical maxim that ‘the King can do no wrong.’ This, Jackson argues, erodes the rule of law itself: ‘No man in this country is so high that he is above the law. All the officers of the government, from the highest to the lowest, are creatures of the law, and are bound to obey it.’

Sri Lanka has no judicial doctrine for classifying presidential acts; instead, it grants temporary immunity for all presidential acts, both official and private, but removes that protection immediately once the term ends. Thus, post-presidency prosecutions are possible, but the standards that guide them remain relatively undefined. The Wickremesinghe case thus poses a larger institutional question: how should presidential conduct be judged, not only after the fact but also during a term in office? Any workable framework must find a way to distinguish governance from politics, duty from self-interest, and the exercise of power from its abuse

What follows from Trump v. United States is more than a dispute over doctrine. It marks the creation of a new legal framework for presidential immunity in which the decisive question is classification: constitutional core, statutory perimeter, or private sphere. The Court’s majority defended this scheme not as a personal indulgence but as a constitutional safeguard, stabilising the separation of powers by insulating governance from prosecutorial intrusion. In its reasoning, immunity was essential to ensure that the presidency could function with the boldness, free from the fear that every contested decision might later be turned into a crime.

Global precedents: Four models of Executive Accountability

The doctrinal structure announced in Trump v. United States is unusually protective of the office of the President. It extends beyond the prevailing global practice by presuming that functional necessity justifies expansive immunity. Other constitutional democracies have confronted comparable problems but have resolved them through different institutional logics. Four models of presidential accountability illustrate the range.

In South Korea, Article 84 of the Constitution provides that “[t]he President shall not be charged with a criminal offense during his tenure of office except for insurrection or treason.” This immunity expires immediately once a president leaves office. There is no functional classification of conduct; all acts are potentially prosecutable once tenure ends. Former President Park Geun-hye was impeached in 2017, convicted of bribery and abuse of power, and sentenced to twenty years’ imprisonment, a judgment upheld by the Supreme Court in 2021 before her pardon later that year. The Korean model thus demonstrates an approach where timing, rather than functional categorisation, determines exposure to liability.

Article 67 of the French Constitution states that the President “shall incur no liability by reason of acts carried out in his official capacity,” subject only to impeachment procedures and the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court. French courts have applied this constitutional distinction by treating campaign and personal corruption as outside the scope of official functions. Former President Nicolas Sarkozy’s conviction for corruption was upheld on appeal in 2023 and became final in 2024. In February 2024, an appeals court affirmed his conviction for illegal campaign financing in the 2012 campaign, modifying the sentence to six months in custody and six months suspended. These prosecutions illustrate a model in which courts classify acts functionally but construe the scope of “official capacity” narrowly.

In Brazil, Article 86 of the Constitution requires a two-thirds vote in the Chamber of Deputies to authorise proceedings; once authorised, the Supreme Federal Court tries a president for common criminal offenses, and the Federal Senate tries impeachable offenses. Investigations may proceed, but a trial on common crimes cannot begin without that legislative authorisation. During the term, the president may not be held liable for acts unrelated to the performance of official duties and is not subject to arrest for common offenses until after a criminal conviction. After leaving office, Jair Bolsonaro faced multiple inquiries, including a 2024 police accusation over falsified COVID-19 vaccination records, with a coup-plot trial set to begin before the Supreme Federal Court in September 2025. The Brazilian model therefore ties accountability to political authorisation, making legislative consent the decisive threshold for criminal liability.

In Israel, the Basic Law distinguish between the ceremonial president, who enjoys both personal and functional immunity, and the prime minister, who does not. Prime ministers may remain in office while indicted unless removed by the Knesset or convicted of an offense involving moral turpitude. Benjamin Netanyahu’s continuing trial on charges of bribery and breach of trust since 2020 exemplifies a system where executive authority confers no constitutional immunity, though enforcement is mediated by political realities.

Taken together, these cases indicate that most systems adopt one of two strategies. Some make immunity purely time-bound and procedural, lifting it immediately after a president leaves office. Others define immunity in functional terms but limit its scope to the narrow domain of acts inseparable from governance. The U.S. approach now stands apart, and the contrast is even sharper when set against Sri Lanka’s constitutional model.

Sri Lanka’s Constitutional immunity

Sri Lanka’s Constitution approaches presidential immunity in a fundamentally different way. Whereas the U.S. model makes category decisive, Sri Lanka makes time the key determinant. In the United States, classification controls: core constitutional powers are absolutely immune, and most acts within the “outer perimeter” of official responsibility are presumptively immune. Any action within those categories that is carried out while in office remains immune from prosecution even after a president leaves office.

By contrast, Article 35(1) of Sri Lanka’s Constitution collapses these distinctions. It declares that “no proceedings shall be instituted or continued against [the President] in any court or tribunal in respect of anything done or omitted to be done by him either in his official or private capacity.” The constitutional protection is sweeping but temporary: it covers all acts during a president’s tenure, yet once the term ends those same acts may be prosecuted.

However, Article 35(1) contains two important carve-outs. First, it allows Fundamental Rights applications under Article 126, though only against the Attorney-General and not the President personally, in respect of acts or omissions by the President in his official capacity. Second, it bars the Supreme Court from reviewing the exercise of the President’s residual powers under Article 33(g). These provisions show that Sri Lanka’s design defers, rather than denies, accountability: it seeks to preserve the dignity of the office of the President while leaving narrow channels for judicial scrutiny even during a president’s tenure.

The difficulty raised by Wickremesinghe’s arrest is not only whether he misused public funds, but how such conduct should be classified. Was the London stopover part of his official duties as president, a symbolic or soft power diplomatic gesture undertaken in his capacity as Sri Lanka’s head of state, or a purely private engagement? The problem is that without such classifications, accountability after office becomes a matter of political discretion rather than constitutional principle. This is where the contrast with the United States is instructive. In Trump v. United States (2024), the Supreme Court sought to address this very problem by constructing a framework for classifying presidential acts

This reflects the tension Chief Justice Roberts warned of in Trump v. United States. He writes that the prospect of post-Presidency prosecution may distort the President’s decision-making, particularly when urgent action is required. Sri Lanka’s model amplifies that concern. Because immunity applies to all acts during office but expires the moment a term ends, the door is opened to politically motivated prosecutions. A president may act boldly while in office yet live under the constant shadow of delayed prosecution. The president is insulated while in office yet exposed to prosecution immediately afterward. Without a doctrinal framework for distinguishing statecraft from private conduct, the result may not be accountability but instability, where legal reckoning risks becoming partisan reprisal.

Political polarisation and rethinking presidential immunity

The constitutional challenge posed by presidential immunity extends beyond the prosecution of former officeholders. What is at stake is the rule of law itself. Can democracies preserve executive independence without eroding executive accountability? Much depends on whether legal systems can distinguish in principled ways between official, political, and personal acts. In Trump v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court attempted to resolve this dilemma through judicial classification and functional thresholds. While that framework protects institutional autonomy, it also risks institutional impunity. The very doctrines that insulate legitimate executive decision-making may now be invoked to shield criminal abuse.

Sri Lanka confronts a different risk. It has no judicial doctrine for classifying presidential acts; instead, it grants temporary immunity for all presidential acts, both official and private, but removes that protection immediately once the term ends. Thus, post-presidency prosecutions are possible, but the standards that guide them remain relatively undefined. The Wickremesinghe case thus poses a larger institutional question: how should presidential conduct be judged, not only after the fact but also during a term in office? Any workable framework must find a way to distinguish governance from politics, duty from self-interest, and the exercise of power from its abuse.

The Wickremesinghe case also highlights the inescapable blurring of public and private life that the U.S. Supreme Court itself acknowledged in Trump v. United States. A president may travel for personal reasons, but the office follows him wherever he goes. Security cannot simply be shed at the airport gate. If a head of state insists on a private trip, does that mean he must forgo protection altogether? If not, does the necessity of a state-funded security detail mean that no aspect of his life is ever truly private while in office? This dilemma extends beyond Sri Lanka. Whatever their differences in immunity and accountability, systems as varied as France, South Korea, and the United States converge on one point: the protection of the head of state is a non-negotiable public obligation, financed by the state whether an act is official or personal.

Furthermore, presidential immunity, in any system, should be understood less as a privilege than as a feature of constitutional design. What that design prioritises, whether institutional protection, prosecutorial discretion, or political bargaining, shapes the future of executive accountability. In both the United States and Sri Lanka, that design is now under strain. The way it is interpreted and reformed will help determine the next phase of democratic resilience.

The polarised decision in Trump v. United States, and the starkly different futures envisioned by the majority and the dissents, demonstrate why the debate cannot be postponed. In Sri Lanka too, the question of presidential immunity has become immediate, not theoretical. It will be contested in courtrooms and in politics, where partisan loyalties and high emotions will frame the terms. The challenge is to recall that the issue is not about Wickremesinghe as an individual, any more than the American case was about Trump alone. It is about the office of the presidency itself. A constitutional democracy must avoid both extremes: the misuse of presidential power while in office and the persecution of former presidents once power changes hands.

(The author is a Visiting Lecturer, and specialises on political science and international relations and could be reached via email at [email protected])