Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Wednesday, 27 November 2024 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

High domestic interest rates on Government debt, combined with the absence of Central Bank intervention to purchase newly issued debt, will escalate the domestic debt servicing burden

Introduction

Introduction

The present article expands on the loss of control by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) of interest rates that we developed in Part I. In Part I the focus was money market or short-term interest rates. In the present article the focus is long-term interest rates, particularly interest rates on long-term Government debt.

The article makes two key points in this regard. Firstly, the CBSL has not only lost control over money market or short-term interest rates, as argued in Part I, but also over long-term interest rates, specifically those on long-term Government debt i.e., on Government debt exceeding one year. Secondly, this loss of control stems partly from the CBSL’s inability to regulate short-term money market rates and partly from the provisions of the new Central Bank Act (CBA) passed in 2023.

The loss of control over interest rates on long-term Government debt

In a recent technical report on the CBSL’s monetary policy, the IMF asserts that the CBSL has not only lost control over short-term money market rates but also over long-term rates (2024, p.9).

In an article we wrote titled ‘An Alternative View of Sri Lanka’s debt crisis’, we argued that one negative consequence of the Central Bank Act (CBA) would be the CBSL’s loss of control over long-term interest rates due to its inability to manage Government bond interest rates. This is because Government bond rates are perceived as setting a floor for longer-term interest rates. We further argued that a second consequence of the CBA would be higher long-term interest rates, driven by increased Government bond interest rates, as these bonds would henceforth carry a risk premium.

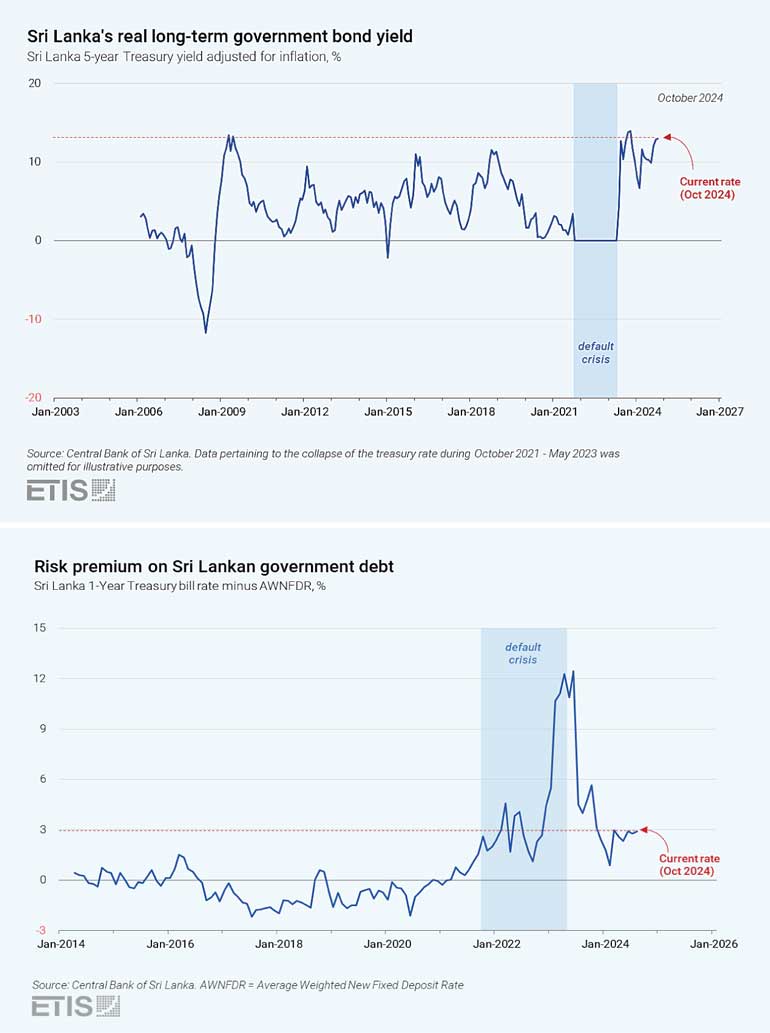

The extent of the CBSL’s loss of control over long-term interest rates is illustrated in the following graph, which plots the real five-year Treasury Bill (TB) rate from January 2003 to October 2024. The real interest rate, rather than the nominal rate, is used because it accounts for the inflation effect on interest rates. The graph shows that the real TB rate during the one-year period from the fourth quarter of 2023 to the present is among the highest in the entire period. This is particularly concerning given that the economy is currently at its weakest point over this period.

It is worth noting that the high real TB rate over the past year persists in spite of, on the one hand, a significant contraction in the budget deficit and, on the other hand, the CBSL providing access to its standing loan facilities to both bank and non-bank primary dealers in Government LKR debt (see IMF, 2024). The provision of access to its standing loan facilities to primary dealers means that the CBSL has in effect been holding down government bond interest rates and, arguably, indirectly financing the Government’s Budget deficit in violation of the spirit—if not the letter—of the Central Bank Act (CBA).

In spite of these ad hoc efforts by the CBSL to moderate the rise of TB rates, it is evident that the CBSL has lost control over these rates, and consequently deposit and lending rates. The chart below depicts the relationship between the one-year TB rate and the average new fixed deposit rate. In a normally functioning market, the fixed deposit rate should exceed the TB rate, reflecting the perception that TBs, being risk-free instruments, carry lower risk than fixed deposits with commercial banks, which are not typically risk-free. However, the chart indicates an inversion of this relationship, with TBs now perceived as not only risky but significantly riskier than fixed deposits.

In spite of these ad hoc efforts by the CBSL to moderate the rise of TB rates, it is evident that the CBSL has lost control over these rates, and consequently deposit and lending rates. The chart below depicts the relationship between the one-year TB rate and the average new fixed deposit rate. In a normally functioning market, the fixed deposit rate should exceed the TB rate, reflecting the perception that TBs, being risk-free instruments, carry lower risk than fixed deposits with commercial banks, which are not typically risk-free. However, the chart indicates an inversion of this relationship, with TBs now perceived as not only risky but significantly riskier than fixed deposits.

This inversion also implies that the TB rate is no longer regarded as the benchmark for retail money market rates, such as deposit and lending rates. As a result, the TB rate can no longer be relied upon to influence long-term retail money market interest rates as in the past.

The source of the problem

The IMF attributes the CBSL’s loss of control over long-term interest rates to its failure to manage short-term money market interest rates effectively. It argues that by gaining control over the latter, the CBSL will be able to exert greater influence over the former. However, what the IMF overlooks is the tenuous link between short- and long-term rates.

An increasing number of central banks, particularly in industrialised countries, recognise that controlling long-term rates often necessitates direct intervention in long-term debt markets (i.e., the purchase and sale of debt in secondary debt markets). If such direct intervention is required to manage long-term interest rates in industrialised countries with developed capital markets, it is even more essential in non-industrialised countries, where capital markets are far less developed and long-term rates are therefore less responsive to movements in short-term money market rates.

What the IMF also overlooks is that the loss of control over long-term rates is a direct consequence of the CBA. Specifically, the CBA introduced a risk element into the pricing of Sri Lankan government debt, where no such element previously existed and where such an element does not exist in most other countries. In most countries, central banks are permitted to purchase government debt, at least in the secondary market, if not in primary auctions. However, following the enactment of the CBA, the CBSL has been explicitly prohibited from purchasing Government debt in the primary and, except in exceptional circumstances, also in the secondary market.

What the IMF also overlooks is that the loss of control over long-term rates is a direct consequence of the CBA. Specifically, the CBA introduced a risk element into the pricing of Sri Lankan government debt, where no such element previously existed and where such an element does not exist in most other countries. In most countries, central banks are permitted to purchase government debt, at least in the secondary market, if not in primary auctions. However, following the enactment of the CBA, the CBSL has been explicitly prohibited from purchasing Government debt in the primary and, except in exceptional circumstances, also in the secondary market.

This prohibition has, for the first time in Sri Lanka’s monetary history, introduced a risk element into the interest rate on LKR Government debt. It signifies that the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) can now theoretically default on both its domestic and foreign debt obligations.

The IMF is ignoring this consequence of the CBA because it, along with the United States, was a prime mover in its passage, repeatedly making it clear that the entire rescue package for Sri Lanka was contingent upon Parliament passing the CBA.

Why is this important?

There will be continuous upward pressure on long-term real interest rates, which is likely to worsen as fiscal pressures increase. These mounting fiscal pressures will arise from the various social and economic commitments made by the current Government. Such pressures could be exacerbated in the short term by the widely anticipated global economic crisis. Given the risks now associated with Government debt, the prospect of heightened fiscal pressure stemming from an expected global economic crisis could lead to rising interest rates, even without an increase in the fiscal deficit. This would occur simply due to market expectations of a deteriorating economic outlook and the negative implications this may have for the Government’s ability to manage the Budget deficit and finance the resulting shortfall without resorting to central bank monetary financing.

Over the long term, fiscal pressures will be aggravated by rising Government debt servicing obligations. High domestic interest rates on Government debt, combined with the absence of Central Bank intervention to purchase newly issued debt, will escalate the domestic debt servicing burden. Furthermore, the ISB debt agreements, with their associated high levels of foreign interest payments, will add significantly to the Government’s overall debt servicing load, particularly from 2028 onwards. Additionally, the IMF has recommended that the CBSL discontinue its use of standing loan facilities to support the domestic Government debt market (2024, p. 21). The concern is that this process could become self-reinforcing. Rising real interest rates and increasing foreign debt servicing costs, within the context of a steadily depreciating currency, will intensify debt burden pressures, heightening market fears of a debt default. This, in turn, could exert further upward pressure on real interest rates on Government debt, and so on.

Rising and volatile real interest rates will have detrimental effects on investment and economic growth. Higher real interest rates will not only increase the cost of capital but also raise the opportunity cost of capital for firms using their own resources. In the case of publicly owned companies, this translates into upward pressure on dividend payouts. One mitigating factor might be the establishment of development banks to provide concessional finance for specific sectors. However, these are unlikely to sufficiently offset the negative effects of elevated and volatile medium- and long-term real interest rates.

References:

Nicholas, H., & Nicholas, B. (2023). An alternative view of Sri Lanka’s debt crisis. Development and Change, 54(5), 1114–1135. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12794

Nicholas, B. & Nicholas H. (2024, November 18) The poverty of the CBSL’s monetary policies: Part I, DailyFT. https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Poverty-of-CBSL-s-monetary-policies-Part-1/14-769383

International Monetary Fund. (2024, September 20). Sri Lanka: Liquidity monitoring and monetary operations (Technical Assistance Report No. 2024/078). https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/technical-assistance-reports/Issues/2024/09/20/Sri-Lanka-Technical-Assistance-Report-Liquidity-Monitoring-and-Monetary-Operations-554970

(Bram Nicholas is the COO of the research and training company ETIS Lanka. Howard Nicholas is a retired associate professor in economics, Institute of Social Studies (The Netherlands).)