Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Tuesday, 5 March 2024 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Many modern quantity theorists accept that central banks do not target and control the cash base, but rather set interest rates leaving the market to determine the quantity of cash put into the system. They argue, however, that in setting interest rates central banks can, and do, target the money stock with a view to controlling inflation. Critics of the modern quantity theory of money have long argued that the money stock depends on loans, i.e., when a commercial bank makes a loan they debit the account of the entity they are lending to, and when commercial banks need cash to meet reserve requirements the central bank has to accommodate this demand

Key elements of the quantity theory

Key elements of the quantity theory

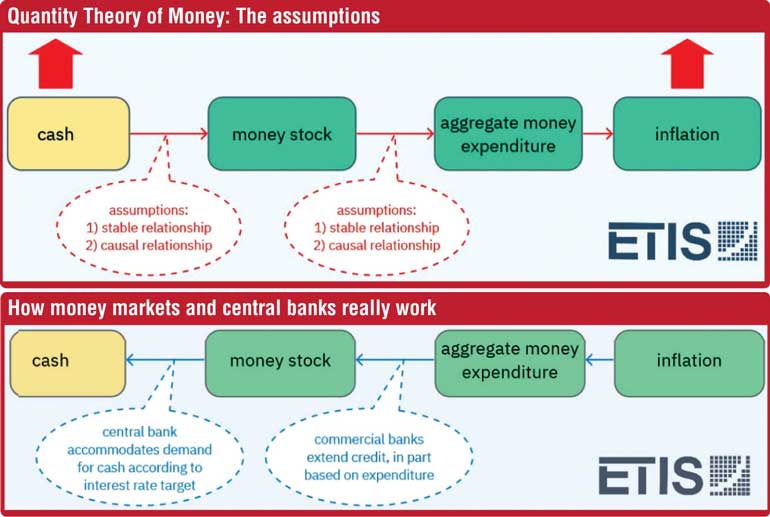

The modern quantity theory of money is basically an explanation of inflation (and the external balance) by an increase in the quantity of money held by the public, the ‘money stock’ that is due to an increase in the cash injected into the system by the central bank of a country (an increase in the ‘cash base’ of the system).

The relation between the cash injected into the system and the money stock (M2) is referred to as the money multiplier. The relationship between the money stock and aggregate expenditure, or more specifically aggregate income, is referred to as ‘the velocity of circulation’. It is assumed that the money multiplier and velocity of circulation are stable and predictable over time, allowing the central bank to control inflation by controlling the cash base.

Many modern quantity theorists accept that central banks do not target and control the cash base, but rather set interest rates leaving the market to determine the quantity of cash put into the system. They argue, however, that in setting interest rates central banks can, and do, target the money stock with a view to controlling inflation.

Critics of the modern quantity theory of money have long argued that the money stock depends on loans, i.e., when a commercial bank makes a loan they debit the account of the entity they are lending to, and when commercial banks need cash to meet reserve requirements the central bank has to accommodate this demand. That is to say, the money stock and cash base are ‘endogenous’ and not ‘exogenous’ as claimed by the quantity theory approach. That is to say, contrary to the quantity theory proponents neither the money stock nor the cash base are determined by the central bank. Rather they are determined by the commercial banks. Central banks only set interest rates, and not with a view to targeting any monetary aggregate.

What mainstream policy-makers and academics say

Holmes 1969 (Senior Vice President, Federal Reserve Bank, New York): “The idea of a regular injection of reserves – in some approaches at least – also suffers from a naive assumption that the banking system only expands loans after the System (or market factors) have put reserves in the banking system. In the real world, banks extend credit, creating deposits in the process, and look for the reserves later.”*

Greenspan 1993 (Chairman of the US Fed 1987-2006): “[I]f the historical relationships between M2 and nominal income had remained intact, the behavior of M2 in recent years would have been consistent with an economy in severe contraction.” Chairman Greenspan added, ‘The historical relationships between money and income, and between money and the price level have largely broken down, depriving the aggregates of much of their usefulness as guides to policy. At least for the time being, M2 has been downgraded as a reliable indicator of financial conditions in the economy, and no single variable has yet been identified to take its place.”

King 1994 (Governor, the Bank of England, and Chairman, the Monetary Policy Committee,

2003–13): “…In the United Kingdom, money is endogenous – the Bank supplies base money on demand at its prevailing interest rate, and broad money is created by the banking system. The endogeneity of money has caused great confusion, and led some critics to argue that money is unimportant. This is a serious mistake.”*

White 2002 (Deputy Governor, the Bank of Canada, 1988–94): “Some decades ago, the academic literature would have emphasised the importance of the reserves supplied by the central bank to the banking system, and the implications (via the money multiplier) for the growth of money and credit. Today, it is more broadly understood that no industrial country conducts policy in this way under normal circumstances. Recognising how unstable in practice is the demand for cash reserves, and the associated implications for interest rate volatility, there has been a decisive shift towards the use of short-term interest rates as the policy instrument. In this framework, cash reserves supplied to the banking system are whatever they have to be to ensure that the desired policy rate is in fact achieved.”*

Friedman, M 2003 (The most renowned exponent of the modern quantity theory of money). In an interview with the Financial Times of London Friedman stated ‘The use of quantity of money as a target has not been a success.’ He added: ‘I’m not sure I would as of today push it as hard as I once did.’ (FT, 7 June 2003).

US Federal Reserve 2005: “[T]he relation between the growth in money and the growth in nominal GDP, known as ‘velocity,’ can vary, often unpredictably, and this uncertainty can add to difficulties in using monetary aggregates as a guide to policy. Indeed, in the United States and many other countries with advanced financial systems over recent decades, considerable slippage and greater complexity in the relationship between money and GDP have made it more difficult to use monetary aggregates as guides to policy. In addition, the narrow and broader aggregates often give very different signals about the need to adjust policy. Accordingly, monetary aggregates have taken on less importance in policy making over time.”

Berry et al. 2007 (The Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin): “When banks make loans, they create additional deposits for those that have borrowed the money.” *

Goodhart 2007: (Monetary Policy Committee Member, the Bank of England, 1997–2000): “... as long as the Central Bank sets interest rates, as is the generality, the money stock is a dependent, endogenous variable. This is exactly what the heterodox, Post-Keynesians [...] have been correctly claiming for decades, and I have been in their party on this.”*

Disyatat 2010 (Bank for International Settlements): “This paper contends that the emphasis on policy-induced changes in deposits is misplaced. If anything, the process actually works in reverse, with loans driving deposits. In particular, it is argued that the concept of the money multiplier is flawed and uninformative in terms of analysing the dynamics of bank lending.”*

Freedman 2010 (Deputy Governor, the Bank of Canada, 1988–2003): “It used to be that most academic research treated money (or sometimes base) as the exogenous policy instrument under the control of the central bank. This was an irritant to those of us working in central banks, because the instrument of policy had always been the short-term interest rate, and because all monetary aggregates (beyond base) have always been and remain endogenous. In recent years, more and more academics, in specifying their models, have treated the short-term interest rate as the policy instrument, thereby increasing the usefulness of their analyses [...].”*

Goodhart 2010 (Monetary Policy Committee Member, the Bank of England, 1997–2000): “The old pedagogical analytical approach that centred around the money multiplier was misleading, atheoretical and has recently been shown to be without predictive value. It should be discarded immediately.”*

European Central Bank 2011 (Monthly Bulletin. October 2011): “The money multiplier framework has a long and distinguished pedigree in the literature. Multiplier analysis is based on the assumption that the central bank unilaterally sets the level of the monetary base, i.e. the monetary base is the instrument of monetary policy. The money multiplier then determines the supply of broad money, while short-term interest rates adjust in order to establish equilibrium between money demand and money supply. Clearly, this account contrasts with the way in which monetary policy is, in general, implemented in practice. In fact [...] central banks set an official interest rate and then supply the volume of reserves necessary in order to steer short-term market interest rates close to the official interest rate.”*

Constâncio 2011 (Vice President, the European Central Bank, 2010–18): “It is argued by some that financial institutions would be free to instantly transform their loans from the central bank into credit to the non-financial sector. This fits into the old theoretical view about the credit multiplier according to which the sequence of money creation goes from the primary liquidity created by central banks to total money supply created by banks via their credit decisions. In reality the sequence works more in the opposite direction with banks taking first their credit decisions and then looking for the necessary funding and reserves of central bank money.” *

Borio 2012 (Bank for International Settlements): “The banking system does not simply transfer real resources, more or less efficiently, from one sector to another; it generates (nominal) purchasing power. Deposits are not endowments that precede loan formation; it is loans that create deposits.” *

Demiralp and Carpenter 2012 (Bank for International Settlements): “The narrow, textbook money multiplier does not appear to be a useful means of assessing the implications of monetary policy for future money growth or bank lending.” *

King 2012: (Governor, the Bank of England, and Chairman, the Monetary Policy Committee,

2003–13): “When banks extend loans to their customers, they create money by crediting their customers’ accounts.” *

Turner 2013: (Chairman, Financial Services Authority, UK, 2008–13): “Banks do not, as too many textbooks still suggest, take deposits of existing money from savers and lend it out to borrowers: they create credit and money ex nihilo – extending a loan to the borrower and simultaneously crediting the borrower’s money account. That creates, for the borrower and thus for real economy agents in total, a matching liability and asset, producing, at least initially, no increase in real net worth. But because the tenor of the loan is longer than the tenor of the deposit – because there is maturity transformation – an effective increase in nominal spending power has been created.” *

McLealy et al 2014 (Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Directorate) “Money creation in practice differs from some popular misconceptions — banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them, and nor do they ‘multiply up’ central bank money to create new loans and deposits.”

Powell J. 2021 (Chairman of the US Fed, 2018-present) “When you and I studied economics a million years ago, M2 and monetary aggregates generally seemed to have a relationship to economic growth. Right now, I would say the growth of M2, which is quite substantial, does not really have important implications for the economic outlook. M2 was removed some years ago from the standard list of leading indicators, and just that classic relationship between monetary aggregates and economic growth and the size of the economy, it just no longer holds. We have had big growth of monetary aggregates at various times without inflation, so something we have to unlearn, I guess.”

Ihrig, et al 2021 (Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis): “While some textbooks provide sound descriptions of these topics, many miss some key aspects of how banks make decisions, inaccurately explain how the Fed implements monetary policy, and contain outdated descriptions of the linkage between banks and the Fed. This outdated link is often tied to the concept of the ‘money multiplier’, which is anchored in an obsolete explanation of how the Fed operates and influences banks. We recommend that textbook authors and teachers eliminate the use of the money multiplier concept in explaining the linkage between banks and the Fed. Instead, we suggest that classroom materials emphasise a contemporary description of how the Fed operates, focusing on changes in interest rates, not monetary quantities, as the mechanism through which Federal Reserve policies are linked with the banking system and the rest of the economy.”

Meanwhile in Sri Lanka

Devarajan in Wijewardena 2019:

“The increase in money supply over and above the required amounts will lead to the elevation of inflation.”

Colombage, S 2020:

“…ever-expanding monetary base will have adverse implications for the economy eventually speeding up inflation and causing severe macroeconomic imbalances.”

Athukorale and Wagle 2022:

“Bouts of high inflation and long-term loss of competitiveness can be directly linked to Central Bank printing money to accommodate the political objectives of the Treasury.” (23)

Coomaraswamy 2023 (Former Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka):

“If the rate of growth of money supply is greater than the nominal growth [sic] of the economy I do not see how this cannot put pressure on prices”

Coomaraswamy, Coorey and Devarajan 2023:

“The exposition of the classical Quantity Theory of Money, while suitable for an introductory course in the history of economic thought, bears little resemblance to current economic thinking in major central banks and academia.”

“Between November 2019 and March 2022, the CBSL directly purchased large amounts of government debt, increasing the cash base (or “reserve money”) by a staggering 51%. Among other things, this drove up inflation to a peak of almost 74% in September 2022 and contributed to a precipitous loss of the CBSL’s foreign exchange reserves and a sharp depreciation of the rupee by 80% between end-December 2021 and end-May 2022…”

IMF 2023 “To rein in inflation, the CBSL has been downscaling monetary financing—purchases of government securities in the primary market have fallen from the peak of a three-month average of LKR 120 billion a month in June 2022 to LKR 43 billion a month in January 2023.” (9)

Jafferjee, M 2023 (Chairman Advocata)

“And the reason that we had inflation in Sri Lanka was there was an excess amount of money chasing too few goods, because the central bank went on monetary financing.”

Weerasinghe 2023 (Current Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka):

In the long run, inflation is primarily caused by factors related to the overall increase in the money supply in an economy relative to the growth in the real output of goods and services.

References:

Athukorale, P. and S. Wagle (2022) The Sovereign Debt Crisis in Sri Lanka: Causes, Policy

Response and Prospects. New York: UNDP.

CBSL (2023) The Central Bank of Sri Lanka Annual Report 2022. Colombo: Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

Colombage, S (2020) ‘Money printing to repay Govt. debt worshipping MMT is likely to magnify economic instability’, Financial Time, 24th December, https://www.ft.lk/columns/Money-printing-to-repay-Govt-debt-worshipping-MMT-is-likely-to-magnify-economic-instability/4-710612

Coomaraswamy, I. (2023) ‘CBSL Amendment Act doesn’t give policy autonomy to the Central Bank’, 17th March, Debate on the CBA organised by the Sri Lanka Economics Association in collaboration with the Economics Students Association of the University of Colombo, at the University of Colombo. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0B6n33pGLLU.

Coomaraswamy, I., Coorey, S. and Devarajan, S. (2023) ‘Why the Central Bank Act should not be amended as the Nicholases suggest’, Financial Times, 5th December. https://www.ft.lk/columns/Why-the-Central-Bank-Act-should-not-be-amended-as-the-Nicholases-suggest/4-755926.

FT (2003) ‘Milton Friedman: There is no such thing as a free lunch’, Financial Times, 7 June.

Greenspan, A (1993) Testimony before the US Senate, Washington, US Federal Reserve.

Gross, M. and Siebenbrunner, C. (2019) ‘Money Creation in Fiat and Digital Currency Systems’, IMF Working Papers, Washington: IMF, WP/19/285.

Ihrig, J. Weinbach, G. and Wolla, S. (2021) ‘Teaching the Linkage Between Banks and the Fed: R.I.P. Money Multiplier’, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis PageOne Economics: Econ Primer, September. https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/page1-econ/2021/09/17/teaching-the-linkage-between-banks-and-the-fed-r-i-p-money-multiplier_SE.pdf

IMF (2023) Sri Lanka Country Report. No 23/116. Washington, DC: International Monetary

Fund

Jafferjee, M (2023) Face the Nation Panelist, 5th July, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OpZ61Tdr08I&t=4904s

McLeay, M., A. Radia and R. Thomas (2014) ‘Money Creation in the Modern Economy’, Bank

of England Quarterly Bulletin 54(1): 14–27.

Powell, J (2021) Semi-annual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress, February.

Weerasinghe, N (2023) ‘Inflation – public enemy number one’, Keynote speech delivered at the University of Colombo Annual Research Symposium, November.

Wijewardena, W.A (2019) ‘Shanta Devarajan: Economist who cannot get disconnected from his motherland’, Financial Times, 19th August. https://www.ft.lk/columns/Shanta-Devarajan-Economist-who-cannot-get-disconnected-from-his-motherland/4-684113.

(Bram Nicholas is the COO of the research and training company ETIS Lanka.)

(Howard Nicholas is a retired associate professor in economics, Institute of Social Studies (The Netherlands).)