Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 16 February 2021 01:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The CBSL is engaged in a lonely battle in restoring economic stability whilst the Government does not seem to make any firm commitment towards reducing its budget deficit, which is the major cause of credit expansion, money supply growth, inflationary pressures and rupee deterioration

Worldwide, central banks face limitations in conducting monetary policy due to the stringent economic rule known as the “policy trilemma”. This rule stipulates that a country’s central bank cannot fix both the exchange rate and interest rates at the same time as long as there are cross-border capital movements.

Worldwide, central banks face limitations in conducting monetary policy due to the stringent economic rule known as the “policy trilemma”. This rule stipulates that a country’s central bank cannot fix both the exchange rate and interest rates at the same time as long as there are cross-border capital movements.

In the case of Sri Lanka, the Central Bank (CBSL) has been struggling hard in recent weeks to keep market interest rates down while preventing further depreciation of the exchange rate. Such efforts are desirable considering the dire socioeconomic consequences that could emerge from sharp interest rate hikes and rupee depreciation during this difficult period of Covid-19 pandemic.

Nevertheless, there are signs of upward movement of market interest rates and rupee depreciation amidst capital outflows, reflecting the dreadful appearance of the policy trilemma.

Policy trilemma explained

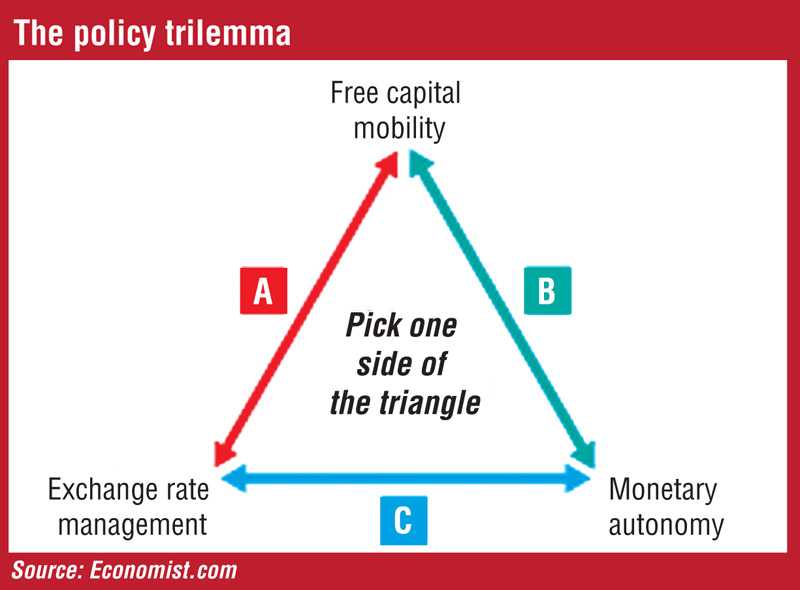

Ideally, any central bank would like to have three properties under its control – monetary policy autonomy, exchange rate stability and free foreign capital mobility. These three properties are placed in each corner of the trilemma triangle, as illustrated in the diagram.

According to the policy trilemma, which is also known as the “impossible trinity”, a country’s central bank can achieve only two out of the three properties, but not all three at a given time.

In other words, a central bank can pick only one side of the triangle as follows:

A = Fixed exchange rate + Free capital mobility

B = Free capital mobility + Monetary autonomy

C = Fixed exchange rate + Monetary autonomy

If the central bank chooses policy option A, then it can fix the exchange rate and allow free capital movements, but it cannot have monetary autonomy. For example, if the central bank tries to keep interest rates low by using its monetary autonomy while maintaining a fixed exchange rate, then capital will move out of the country.

If exchange rate management is not sacrificed in option B while trying to keep interest rates low, again there will be capital outflows.

In option C, the central bank can fix both the exchange rate and interest rates, but it has to forego free capital movements.

Exchange and interest rates are inversely linked

The policy trilemma simply means that whenever a country’s interest rates are too low, its currency becomes less valuable, and therefore, the currency should depreciate so as to discourage capital outflows.

This is based on a well-established theorem known as the interest rate parity (IRP) in economic literature. No central bank can beat this rule without exerting adverse consequences on the economy.

Monetary easing in Sri Lanka

In order to recover the economy severely hit by the pandemic, the CBSL has implemented a number of unprecedented monetary easing measures since early last year, in common with many other central banks across the globe.

As a result, both deposit and lending rates have come down in recent months. For instance, the yield rate of three-month Treasury Bills is down to 4.75% by now from 7.36% a year ago. The Average Weighted Lending Rate (AWLR) of commercial banks has declined to 10.29% from 13.59% a year ago.

These downward interest rate movements have helped to marginally raise bank credit to the private sector, as discussed in my article in Daily FT (http://www.ft.lk/columns/Bank-credit-to-private-sector-picking-up-at-slow-pace-in-response-to-monetary-easing/4-712502).

Forex restrictions

Considering the adverse effects of rupee depreciation and reserve depletion, the CBSL has taken several steps since last year to restrict foreign exchange transactions. This is in addition to the import restrictions in place.

But the exchange rate has been under severe stress due to foreign exchange shortfalls coupled with mounting external commitments. The Government has to settle Sri Lanka Development Bonds amounting to $ 1,325 million by next August. In addition, an International Sovereign Bond of $ 1,000 million will have to be settled in July this year.

Fiscal consolidation needed

While the CBSL is attempting to maintain the exchange rate and interest rates within desirable ranges, there does not seem to be adequate cooperation coming from the fiscal side to contain the budget deficit so as to ease monetary management.

Bank credit to the Government and public corporations rose by as much as 62.7% and 22.5%, respectively in 2020. In comparison, private sector credit growth was only 6.5%, in spite of the various concessions offered during the pandemic.

In the background of drastic revenue cuts and expenditure hikes, the budget deficit is likely to be around 10% of GDP this year. This implies that demand for domestic bank credit will continue to rise exerting pressures on the money supply, interest rates, inflation and the exchange rate.

Interest rate hikes and rupee depreciation imminent

There are signs of upward movements of interest rates in the near future. Heavy undersubscription of Treasury Bills (TB) in recent auctions reflects the public’s dissatisfaction about the low returns, and this would compel the authorities to increases the yield rates in coming weeks. A marginal increase in TB yield rates was evident in the last week’s auction, reflecting a turnaround of market interest rates.

It has become difficult to attract foreign investors for International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) in recent auctions, and therefore, the Government will have to borrow more and more from the domestic market, thus pushing up interest rates. The two swap agreements with India and China, which amounts to $ 2.5 billion, are still said to be under negotiation.

In the absence of exchange rate flexibility, the trade deficit is likely to widen, and capital outflows will continue, as per IRP theorem. The exchange rate has depreciated so much that it touched Rs. 200 per US dollar a few days ago, and it was brought down subsequently.

Capital outflows

According to the IRP theorem, low interest rates and exchange rate rigidity encourage foreign investors to take their capital out of the country. This tendency is evident in Sri Lanka by now.

The net amount of foreign investment outflows from Government Treasury Bills and Bonds amounted to $ 553 million in 2020. The total outstanding amount of foreign investment in rupee denominated Government securities remained low at $ 37 million by the end of 2020.

Also, there were net outflows from primary and secondary markets of the Colombo Stock Exchange amounting to $ 225 million in 2020, and such outflows are continuing this year as well.

Need for independent Central banking

The CBSL bears the brunt of economic stabilisation burden while the Government continues its spending spree increasingly depending on bank credit. It is in this context that the phenomenon of independent central banking becomes crucial.

Central bank independence refers to freeing the monetary authorities from direct government influence so as to enable them to focus on price and economic stability, rather than adopting populist policies to satisfy the voters according to whims and fancies of politicians.

This phenomenon is fading away fast across the world nowadays, as central banks are compelled to abide by the governments’ decisions to inject liquidity into the market in unprecedented scales to revive the economic activities paralysed by Covid-19 pandemic. Sri Lanka’s central bank is no exception.

Inflation underestimated

Various arguments have been brought forward in official circles to justify the high money growth and low interest rates. Excessive money printing to repay public debt is said to be harmless in terms of the awkward Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). It is also argued that the country’s inflation remains low despite the unemployment rate being fallen to near-full employment level.

However, alternative price indices such as the Producer Price Index (PPI) reflects much higher inflation, in contrast to the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI) which is popularly used for official purposes, as explained in my last week’s FT column (http://www.ft.lk/columns/Inflationary-pressures-on-the-horizon/4-712891).

Hard policy choices

Given free capital mobility, the CBSL has no choice other than to give up either fixing the interest rates or fixing the exchange rate, in terms of the policy trilemma.

Simultaneous suppression of the two rates leads to capital flights, as already evident in the Government securities and stock markets of Sri Lanka.

The CBSL is engaged in a lonely battle in restoring economic stability whilst the Government does not seem to make any firm commitment towards reducing its budget deficit, which is the major cause of credit expansion, money supply growth, inflationary pressures and rupee deterioration.

Monetary policy autonomy has become important now more than ever, as central banks in many countries are compelled to follow government directives in a subservient manner to inject liquidity into the market so as to resuscitate the economies adversely affected by the pandemic.

Eventual erosion of central bank independence in the backdrop of the pandemic has compelled the CBSL to bear the brunt of macroeconomic rectification.

It is reported that an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) would not be feasible due to the Government’s decision to take a different policy path that includes import restrictions and managed exchange rate.

While such policy alternatives might be praiseworthy from different perspectives, there is the danger that indefinite postponement of imperative structural adjustments is likely worsen the macroeconomic disarrays beyond repair.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and Visiting Fellow of the Advocata Institute. He is a former Director of Statistics of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, and reachable through [email protected])