Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Wednesday, 27 November 2024 00:24 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The symbolic exclusion signalled by the missing Muslim at the highest level of governance is significant and no amount of patronising rhetoric about our collective Sri Lankanness is going to address this sense of exclusion

The change that the new election has brought to the country is unprecedented. We have a woman Prime Minister (that many of us in the academic and activist communities know) and we have several young women in Parliament. Historically, since independence, we have only had 5% representation at any given moment. Now we have close to 10%. And that too through elections and only one through the national list.

The change that the new election has brought to the country is unprecedented. We have a woman Prime Minister (that many of us in the academic and activist communities know) and we have several young women in Parliament. Historically, since independence, we have only had 5% representation at any given moment. Now we have close to 10%. And that too through elections and only one through the national list.

Combined with the local Government quota of 25% introduced after many struggles, we have a huge transformation in women entering leadership positions. We also have a Parliament full of people who under earlier dispensations were not permitted in and we have a Government committed to raising up the economically and socially marginalised. The promise of an NPP Government is felt by all across the country and the expectations are high.

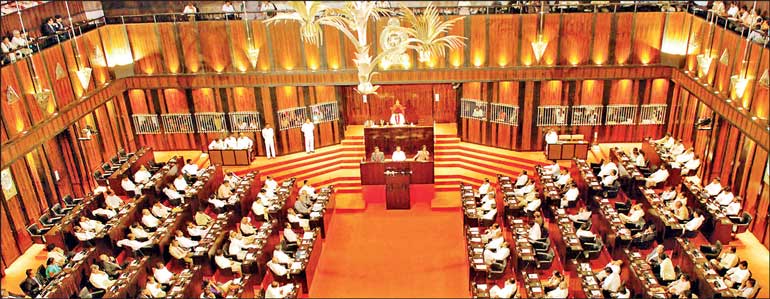

The NPP’s victory with a stupendous two-third majority while impressive for the party may possibly be a problem for the country. Such a mandate has not, so far, brought about salutary results for the Sri Lankan population. It is to be seen if it will in the case of the NPP Government. At a minimum therefore it is important that those of us watching political developments respond in a manner that offer course corrections for the Government when necessary and provide a critical language to ensure that the Government prioritises the people’s will in their governing.

Two issues Govt. must pay attention to

There are two issues today that the Government must hear and pay attention to. The first is their commitment to women’s representation and leadership and the second is their inclusion of minority representation in leadership positions. Their progress to date has been wanting and requires comment.

There are 19 men in the 21-member cabinet of ministers and there are 29 men appointed as deputy ministers. There are only two women in the 50-member Cabinet. That is a 96% male, and only 4% female Cabinet. This troubling commitment on the part of the NPP leadership to walk the talk re women’s inclusion only minimally and at the level of optics alone must be called out. Their election mobilising that brought thousands of women into the limelight and elevated the very capable Dr. Harini Amarasuriya to the position of Prime Minister garnered widespread recognition, support and a lot of great press.

Harini Amarasuriya with her feminist credentials and class clout and her laudable public engagement was the NPP’s effectively used ticket out of the doldrums. But the Cabinet appointments are an indication that Harini herself has not been able to elevate women’s participation to an actually meaningful level within the NPP. The NPP’s actions show a lack of appreciation for the real effects that women’s participation in leadership need to have and look like.

Then the question of the Muslim representation in Cabinet. As the NPP leadership keeps telling us, it is important that there is a Muslim governor appointed for the Western Province, a Muslim deputy speaker and one Muslim deputy minister; important that eastern Muslim representation to Parliament was assured through MP Athambawa. This minor acknowledgement of the importance of all people’s presence in positions of authority can perhaps be appreciated. Given all the salutary developments connected to the NPP victory, the lack of a Muslim Cabinet minister was perhaps one issue that we could have had a wait-and-see approach to if we had had a sensible explanation as to why it happened and how the NPP Government plans to address Muslims’ sense of exclusion.

Then the question of the Muslim representation in Cabinet. As the NPP leadership keeps telling us, it is important that there is a Muslim governor appointed for the Western Province, a Muslim deputy speaker and one Muslim deputy minister; important that eastern Muslim representation to Parliament was assured through MP Athambawa. This minor acknowledgement of the importance of all people’s presence in positions of authority can perhaps be appreciated. Given all the salutary developments connected to the NPP victory, the lack of a Muslim Cabinet minister was perhaps one issue that we could have had a wait-and-see approach to if we had had a sensible explanation as to why it happened and how the NPP Government plans to address Muslims’ sense of exclusion.

Muslim concerns regarding lack of representation

Ministers Bimal Ratnayake and Vijitha Herath recently, however, have dismissed Muslim concerns regarding the lack of representation. Their refusal to acknowledge Muslims’ concerns was frankly more disturbing than the lack of representation itself. Suggesting that the NPP’s almost entirely Sinhala cabinet are better at addressing the concerns raised by the Muslim community than a Muslim representative, both ministers shrugged off the anxiety that Muslims have regarding their exclusion from the highest leadership level. The ministers called it an unfair criticism, a wrongheadedness and a dated ethnicised/racialised concern that is not in line with their policies.

Both ministers made no effort to hear the fears expressed and did nothing to allay them. In both instances their irritation was clear—more obvious in the case of Vijitha Herath in Akurana—and indicated a disregard for any thinking or position outside the one worked out by their JVP led inner circles. This is troubling. The uproar re the lack of a Muslim appointment occurred when the Cabinet was announced. It did not die down after the Muslim deputy speaker and deputy minister of national integration appointments were made. It is important that the NPP at least hears what is being said by the larger Muslim community and think for a moment about how to substantively address this disquiet.

The symbolic exclusion signalled by the missing Muslim at the highest level of governance is significant and no amount of patronising rhetoric about our collective Sri Lankanness is going to address this sense of exclusion. A considered and thought through response recognising Muslims’ concerns about the lack of representation, and a commitment to putting measures in place to have Muslim concerns recorded and addressed if and when they arise would have gone a long way to allay fears in the absence of an actual appointment.

In addition to the issue of Cabinet representation, the relative absence of Muslims at the highest level of the NPP leadership is a problem that the NPP needs to reflect upon and address. It cannot be sidestepped with platitudes about their good intentions. This is not to say that the Muslim community position is fully thought through. How the diverse Muslim groupings understand what representation should look like too is not clear.

A non-nationalist future

The new Government’s anti-corruption and anti-nationalist platform seems to assume that it addresses all the ills of the country’s past; it needs to now include thought through solutions to the country’s history of targeted minoritisation and marginalisation of Tamil and Muslim citizens and the decades of war. While positing an idea of Sri Lankanness is well and good, the Government need to also think about how it looks to minoritised communities when the leadership of this new Sri Lankan nation does not include them. If the regime is truly committed to a non-nationalist future where all communities feel a sense of belonging, more thought needs to go into what this can actually mean.

The regime must ensure that those who have been rendered minor in the past have a role in the rebuilding for the future. The NPP’s stated priority is the economy. But changing the political culture—as the regime promises to do everyday—should prioritise the substantive contribution of all citizens – women and minorities (and minority women) included. Most importantly the Government should not be seen as unwilling to hear the concerns of the citizens.

(The writer is Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Colombo)