Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 20 May 2025 02:16 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the latest buzzword. Every industry and profession seems to be concerned about how AI is impacting their work. Discussions are unfolding not only about integrating AI tools to enhance efficiency, but also whether some advanced AI systems could replace certain human held jobs.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the latest buzzword. Every industry and profession seems to be concerned about how AI is impacting their work. Discussions are unfolding not only about integrating AI tools to enhance efficiency, but also whether some advanced AI systems could replace certain human held jobs.

The media industry and media profession are also beginning to have such conversations. It is clear that AI is becoming an invaluable tool in journalistic processes. Various AI software systems are available, and being used in newsrooms around the world, for tasks like news packaging, fact-checking, and content personalisation. This is only the beginning.

AI has entered Sri Lankan newsrooms too, albeit mostly at experimental levels. The adoption is driven by digital media startups and younger professionals in legacy media companies (newspapers, radio and TV).

The topic had been discussed at the Sri Lanka Media Festival 2025 held recently in Colombo. A panel looked at the “opportunities, threats and ethical concerns surrounding AI integration into journalism” according to media reports. (https://www.ft.lk/news/Experts-unpack-how-AI-is-rewriting-journalism-s-future/56-776005).

Kalindu Karunaratne, news manager of a leading broadcaster, had highlighted the inadequate technological integration in the local media sector and “called for training and rules limiting the exploitation of AI”. Echoing a growing call worldwide, he said that newsrooms need to be transparent about AI-generated content.

Transparency and other ethical considerations must indeed underpin the media’s AI use, especially for journalism. Conversations should not be limited to optimising AI tools to life easier for its practitioners. Tech adoption should ideally happen within the framework of both emerging AI ethics and well-articulated journalism ethics.

World Press Freedom Day (WPFD) 2025, observed globally on 3 May, enabled some timely reflections on this front. This year’s theme was ‘Reporting in the Brave New World: The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Press Freedom and the Media’.

UNESCO, the UN agency mandated to promote freedom of expression, media freedom and media development, notes how “the unprecedented use and development of AI systems are now playing a transformative role in journalism, media, and human rights with unforeseen consequences. Despite these changes, the core values of a free, independent, and pluralistic media…remain as crucial as ever.”

AI: Boon and Bane

For journalists willing to learn and upskill themselves, AI offers many benefits. AI tools can make it easier to perform tedious tasks such as interview transcribing, content summarising, data analysis and fact checking. Though still imperfect for some languages, AI also enables instant translations between languages. Using AI as virtual journalistic assistants would free up time for journalists to engage in more in-depth reporting and investigations.

But as UNESCO warns, AI is a double-edged sword that must be wielded with great caution. Uncritical adoption of AI can lead to journalistic lapses and excesses that can have serious societal consequences.

This is because the very AI tools that improve efficiency and reduce drudgery can also amplify systemic biases, enable easier surveillance of journalists (and their sources), and exacerbate online abuse – particularly targeting women journalists and marginalised voices.

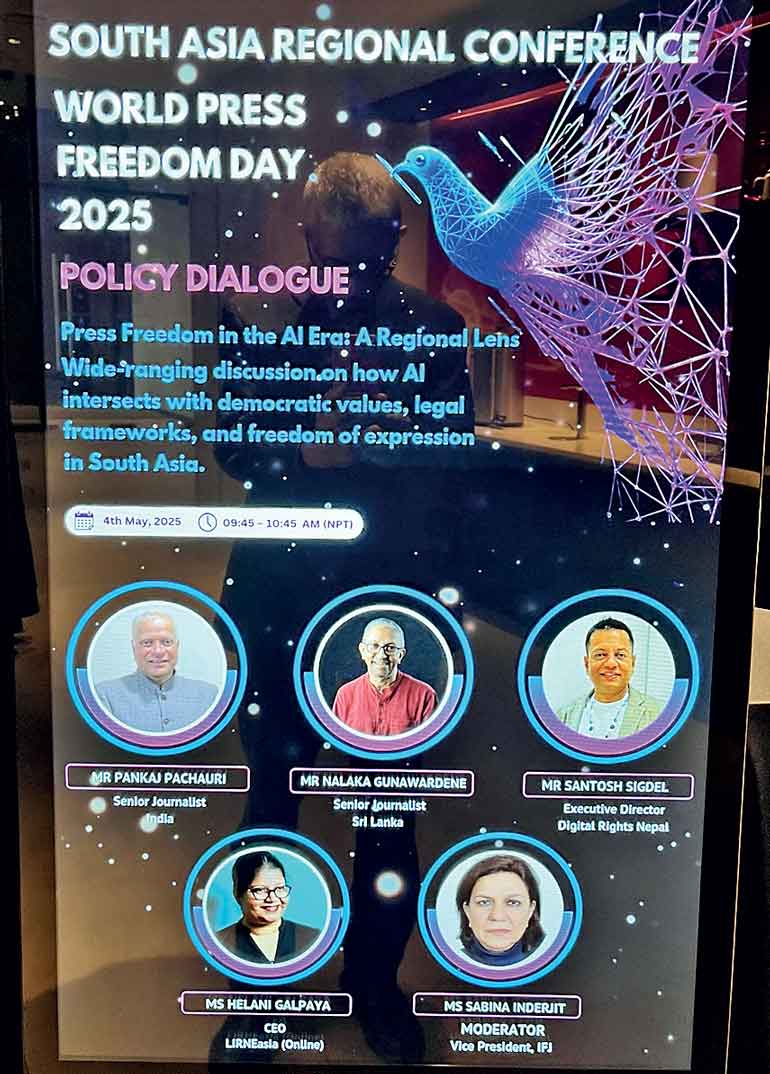

To help explore these issues from a regional perspective, UNESCO held a South Asian conference in Kathmandu, Nepal, on 4 May. Convened by the UNESCO office in Nepal, the conference brought together a few dozen journalists, editors, civil society actors, policymakers, academics and digital rights advocates from across the region.

I was invited to speak on the opening panel on the policy and regulatory challenges. This article captures and expands on key points I made, and some other perspectives shared there.

Dystopia not inevitable

Two kinds of reactions are common when confronted with any new technology.

Some would allow themselves to be mesmerised by its capabilities, while others would imagine the worst-case scenarios of misuses and abuses. In fact, Brave New World is the title of a well-known dystopian novel written almost a century ago by English author Aldous Huxley. Its story takes place in a world 500 years from now, when human agency is all but lost to intelligent machines.

However, a more nuanced and measured response is also possible – and more desirable – to any new technology.

Through history, new information and communication technologies (ICTs) have presented a mixed bag of opportunities and challenges. Each innovation also replaced those who were doing tasks manually: Medieval book writers, who painstakingly and beautifully hand crafted every book copy, lost their jobs to the printing press. But printing soon created new jobs that didn’t exist.

Twenty-first century technologies evolve more rapidly and present more complex challenges as well as unintended consequences. The social critic’s question about any new technology being a boon-or-bane needs revisiting: today, technologies are both a boon and a bane. Policymakers must therefore help optimise benefits and take action to minimise risks.

AI may be currently trending, but the digital transformation of the media industry has been happening since at least the year 2000. As UNESCO notes, the media landscape across Asia has experienced wave after wave of tech-driven changes. These are driving mobile-first news consumption, the proliferation of diverse digital platforms challenging legacy media, and the growing influence of social media as primary sources of information.

Knowingly or not, journalists have been using AI tools and services for over two decades. Google – which began as a smarter search engine 26 years ago – is a common example of an AI-enabled service that has become indispensable. Voice assistants like Siri and Alexa are other examples. These and other AI services help users to search, rank, analyse, interpret or otherwise make sense of growing volumes of digitally available data.

In contrast, Generative AI – like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini and Microsoft’s CoPilot, to mention just a few examples – represent the next generation. Based on existing data and driven by human instructions, GenAI can create wholly new content as text, images, videos or music. Such machine-generated materials are collectively known as synthetic content.

UNESCO WPDF South Asia Conference Banner Synthetic vs. authentic content

Generative AI opens many possibilities for journalists and media companies. For example, tasks like data visualisation and creating customised images, audio or video becomes much easier. Text synthesis tools can churn out grammatically correct paragraphs on a given topic within seconds.

However, it has become harder to discern synthetic content from authentic (human-generated) content especially with Generative AI tools improving their sophistication with each new version. In other words, unless labelled as such by originators, many items of synthetic content can pass as authentic. This is especially problematic for journalistic photographs, audio and video.

South Asia’s media regulators haven’t yet caught up with this reality to make it a requirement. In India, from January 2025, the Election Commission requires political parties and candidates to clearly label any AI-generated or significantly altered content used in election campaigns. The Indian Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) also issued an advisory in March 2024 requiring online platforms and intermediaries to label AI-generated content, especially when such content could potentially spread misinformation.

In all other cases and countries including Sri Lanka, it remains a voluntary, ethical responsibility for media to disclose synthetic content. A few media outlets do, but many don’t practice AI labelling or watermarking. As we already know, adhering to media ethics is widely considered as optional, not obligatory, by many of South Asia’s numerous and cacophonous media.

That, in turn, can easily mislead media audiences to believe a synthetic content as authentic. In the hands of disinformation originators, Generative AI easily becomes weaponised to pass off the fabricated as real or authentic.

The same weekend we were meeting in Kathmandu, US President Donald Trump posted an AI image of himself dressed as the pope. That appeared to be a spoof in bad taste, but as the Indian journalist Pankaj Pachauri noted, millions of naïve young social media users in India readily believed that Trump had succeeded Pope Francis!

That particular delusion may be harmless, but that is often not the case. In politically charged times that we South Asians live in, a maliciously fabricated synthetic content could lead to unrest and even violence.

Deepfakes and shallow fakes

This takes us to the realm of deepfakes, defined as an image or recording that has been convincingly fabricated or altered to misrepresent someone as doing or saying something that was not actually done or said.

Perhaps the best known deepfake concerning Sri Lanka to date is the November 2023 video of a woman, claiming to be Dwaraka, daughter of the LTTE leader Prabhakaran. She is believed to have perished with her family in the final days of the civil war in May 2009. But when the video emerged in social media and went viral in southern India and Europe, some believed it to be real. Yet the intelligence agencies in both India and Sri Lanka said it was deep-faked.

Deep Fakes and their abuses have drawn lots of media attention, but they are only one facet of AI impact on inauthentic or synthetic content. I argued in Kathmandu that in many South Asian situations, elaborately produced deepfakes are not even necessary to mislead the public: the same deception could be achieved by ‘shallow fakes’, or manipulated content that doesn’t require advanced technology.

Shallow-faked images done manually with photo or video editing software have been around for years and now co-exist with deepfakes. For example, in Sri Lanka’s Presidential and Parliamentary Elections in late 2024, we had expected to see lots of political deepfakes to circulate. In the end, shallow fakes were more abundant, and arguably just as effective in misleading some voters!

Kathmandu-based investigative journalist Deepak Adhikari agreed with me saying AI-generated disinformation fears were hyped. Instead, he argued how we need to consider the entire media and information landscape and assess how fabrications and deceptions -- of whatever provenance -- are impacting public opinion and voter behaviour.

To see this bigger picture, we need step back from AI and digital domains and consider the totality of how our people seek, find and react to information: in analogue and digital sources, with myriad interactions happening both online and offline. Most people don’t live or work or vote in a digital bubble alone!

We also need to acknowledge and address the pre-digital gaps and capacity limitations in our media. Whether in analogue or digital contexts, some journalists and editors simply don’t know how to handle ethical dilemmas – AI can only make matters worse.

Meanwhile, some media houses are not accountable to their audiences or even to media regulators, taking cover under media freedom and crying ‘censorship’ when attempts are made to hold them to account. Some media outlets cynically adopt a bare minimum compliance of regulations, adhering to the letter -- but not the spirit -- of accountability. Local examples abound.

These existing gaps will be exacerbated when AI tools enhance media’s ability to generate and distribute new kinds of content. Whether in analogue or digital content, the fundamental media ethics – such as verifying all information, maintaining independence, and practising impartiality – form the essential safeguards against media malpractices.

Paris Charter

The bottomline: South Asian media need to get their houses in order before the AI disruption soon overwhelms them. An already ethical media would find it easier to accommodate the new layer of ethical challenges coming with AI.

A good starting point around these issues is the Paris Charter on AI and Journalism, adopted by 16 media rights and media development organisations in November 2023. Its concise yet powerful text was drafted by an international group of experts headed by Nobel Peace Prize winning journalist Maria Ressa.

Its preamble says, “The social role of journalism and media outlets — serving as trustworthy intermediaries for society and individuals — is a cornerstone of democracy and enhances the right to information for all. AI systems can greatly assist media outlets in fulfilling this role, but only if they are used transparently, fairly and responsibly in an editorial environment that staunchly upholds journalistic ethics.” [emphasis added]

The Paris Charter acknowledges transformative benefits of AI to media but also cautions how AI tools present a structural challenge to the right to information which flows from the freedom to seek, receive and access reliable information.

The Paris Charter’s 10 principles can be summed up in four points:

Do we have sufficient awareness of these concerns? The Paris Charter process was led by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), and among its 16 original signatories is the Asia-Pacific Broadcasting Union (ABU), a professional association of broadcasters that includes many in South Asia.

The South Asian media can adopt the Paris Charter as the guiding framework; or adapt it with some regional modifications; or develop their own. Whatever is decided, the journalists and media managers need to drive the process, not theory-laden media academics!

Recognise digital limits

Finally, South Asian media need to recognise limitations of AI tools due to the region’s own circumstances.

Fellow panellist Helani Galpaya, CEO of the ICT thinktank LIRNEasia, highlighted how a good portion of South Asian public data is simply not available in digital or machine-readable formats. Many government agencies continue to collect and store data on paper: journalists cannot use AI tools to analyse these.

An extension of this limitation is that some data may exist digitally but not placed online due to absurd bureaucratic limitations.

Another challenge shared by Sinhala and other local language media across South Asia: AI tools are not optimised for use in our languages. Sinhala is a resource-poor language, with limited linguistic data and resources available for training AI models. Many other regional languages share this limitation.

In practice, this means the quality of Generative AI outputs in such languages is inferior to outputs in English or Chinese or other international languages. A simple test of this is to enter the same prompt to ChatGPT in a local language and English.

In time to come, these disparities may be reduced. But what can journalists and other AI users do in the meantime? To have easy access to analytical and generative AI tools but without accessible and useable data would place South Asian journalists on the wrong side of the AI divide.

Tackling these structural issues requires South Asia’s media outlets – both digital startups and legacy media – to stay engaged in global discussions on internet governance and AI governance. If we don’t turn up and highlight our own needs and challenges, no one else would speak for us.

(Trained as a science writer, the author is widely experienced as a journalist across print, broadcast and web outlets covering issues related to science and sustainable development issues in Sri Lanka and across developing Asia. For over a decade, he has worked as a media analyst and media development specialist, working with governments, media companies and international organisations in developing strategies for accountable journalism, media resilience, and collaboration with global tech platforms. His Twitter/X handle is @NalakaG.)