Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday, 23 February 2024 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

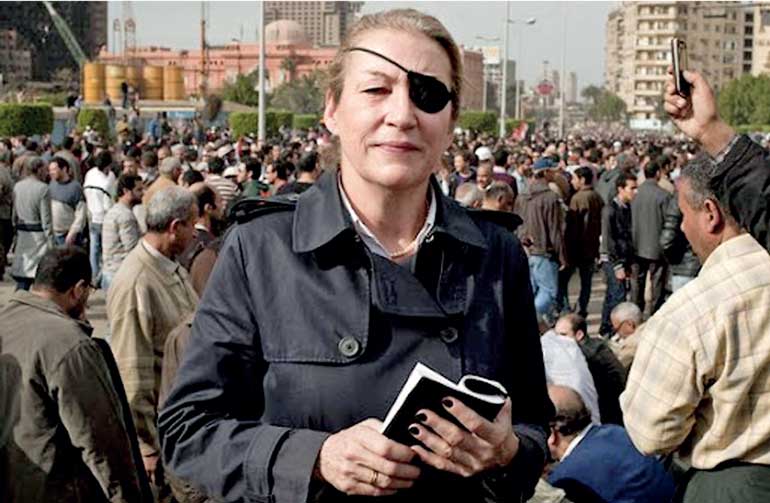

The life and work of Marie Colvin is multi-faceted and a manifestation of exemplary bravery and commitment

The life and work of Marie Colvin is multi-faceted and a manifestation of exemplary bravery and commitment

It is said of war correspondents that they have to “Get in, Get it and Get out”. Marie did just that in many conflict zones from Chechnya to Bosnia, from Sri Lanka to Syria. In Sri Lanka she lost an eye but in Syria she lost her life. She got in, got it but couldn’t get out. To her credit it must be said that she had the option of leaving like many other scribes but opted to stay on and report the travails of ordinary civilians in war situations. One of her final reports was a first person account of seeing a baby die

Marie Catherine Colvin, the respected war correspondent of Britain’s “Sunday Times” was targeted and killed on 22 February 2012 by Syrian forces as she reported on the suffering of civilians in Homs, Syria. At the time of her death, Marie Colvin was reporting from the Baba Amr Media Centre, a makeshift broadcast studio run by Syrian media activists in a secret facility located in a residential building.

Marie Catherine Colvin, the respected war correspondent of Britain’s “Sunday Times” was targeted and killed on 22 February 2012 by Syrian forces as she reported on the suffering of civilians in Homs, Syria. At the time of her death, Marie Colvin was reporting from the Baba Amr Media Centre, a makeshift broadcast studio run by Syrian media activists in a secret facility located in a residential building.

The rocket attack also killed acclaimed French photographer Rémi Ochlik and injured British photographer Paul Conroy, Syrian translator Wael al-Omar and French journalist Edith Bouvier. A Syrian photojournalist was also killed in the attack.

Both Marie Colvin and Remi Ochlik had tried to flee when the building in which they had been staying came under artillery shelling. “As they tried to escape, Colvin and Ochlik were hit by a rocket and killed,” a statement issued by the “Sunday Times” said. It was later revealed that the Syrian military and intelligence tracked the broadcasts of the journalists covering the siege of Homs, and then targeted the media centre in a barrage of artillery fire.

Journalists in the line of duty are required to write about different people from all walks of life but it is very rarely that they write about themselves or fellow journalists. It is accepted as part of a scribe’s lot in life. As far as the fourth estate is concerned, it goes with the territory.

Sadly, if at all we do write about a journalist, it is only after he or she passes away. It is against this backdrop therefore that I write this week about journalist Marie Colvin who was regarded as the greatest war correspondent of her generation. I have written about her on earlier occasions too and will rely on those writings for this article denoting her 12th death anniversary.

The death of Marie Colvin on 22 February 2012 diminished the world of intrepid journalism. A world where she was undoubtedly the uncrowned queen. At a personal level, her demise was distressing to me because I was slightly acquainted with her. I have communicated a few times on the telephone and exchanged a few e-mails with her in the past, particularly during that tragic phase in 2009 when many of us were engaged in a futile effort to prevent a humanitarian catastrophe from happening in northern Sri Lanka. I have never met her in person; something which I regret very much.

Empathy for underdog

Through my brief interaction, I found her to be an ebullient and refreshingly-candid person with a lively sense of humour. Marie had an insatiable curiosity about many things. I admired her greatly for her courage, passion and devotion to reporting. Above all, I recognised a kindred spirit in her empathy for the perceived underdog.

Marie Colvin made her mark as a journalist in Britain but was by birth an American. She was a frontline warrior for truth in journalism. Infused with a sense of daring and a zest for adventure Marie ventured into the troubled hotspots of the globe. She defied authoritarian regimes by circumventing controls and barriers and infiltrating war zones.

Some compare Marie Colvin with Martha Gellhorn the legendary woman war correspondent who covered many wars and battles for several decades always keeping the plight of the affected civilians as her focus. Martha incidentally was married for a few years to Ernest Hemingway. Martha and Marie were friends.

“Get in, Get it and Get out”

It is said of war correspondents that they have to “Get in, Get it and Get out”. Marie did just that in many conflict zones from Chechnya to Bosnia, from Sri Lanka to Syria. In Sri Lanka she lost an eye but in Syria she lost her life. She got in, got it but couldn’t get out.

To her credit it must be said that she had the option of leaving like many other scribes but opted to stay on and report the travails of ordinary civilians in war situations. One of her final reports was a first person account of seeing a baby die.

Dickey Chappelle

I don’t know whether it is in my blood or in my stars but I have been fascinated by writers, poets and journalists since childhood. One of my earliest heroes or heroines was Dickey Chappelle born as Georgette Louise Meyer. I first became aware of her when I read the condensed version of her book “What’s a woman doing here”? in the Readers Digest. Later on I read the whole book.

Dickey covered the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa during World War 2. Later she was jailed in Budapest when she covered the Hungarian uprising of 1956. She gained fame by covering the Cuban revolution led by Fidel Castro which overthrew Batista. She died in 1965 in Vietnam while trekking with a military patrol when shrapnel from an exploding booby trap struck her neck inflicting fatal injury.

I think Dickey Chappelle and Marie Colvin were of the same ilk and met their deaths while engaged in the pursuit of news. They died with their boots on. Unlike Dickey Chappelle, Marie Colvin played a role in Sri Lankan affairs.

April 2001 in Sri Lanka

In April 2001 she was in Sri Lanka and had an appointment on 4 April with the then foreign minister Lakshman Kadirgamar for an interview. In the meantime she tried to get official permission to go to the Wanni for an interview with Suppiah Paramu Thamilselvan, the political commissar of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) at that time.

As was the norm then she was denied permission as the LTTE controlled Wanni was a “no go zone” for foreign correspondents. But Marie managed to get around that hitch by clandestinely infiltrating the Wanni through a jungle route north of Vavuniya with the help of the Tigers. She failed to turn up for the scheduled interview with Kadirgamar.

Through my brief interaction, I found her to be an ebullient and refreshingly-candid person with a lively sense of humour. Marie had an insatiable curiosity about many things. I admired her greatly for her courage, passion and devotion to reporting. Above all, I recognised a kindred spirit in her empathy for the perceived underdog

She filed reports for her paper while in the Wanni. This included the Thamilselvan interview. The Colombo establishment realised that Marie Colvin had defied their restrictions and gone into forbidden territory.

At that time the Government declared a five-day ceasefire to coincide with the Sinhala-Tamil New Year in mid-April. Marie Colvin utilised the ceasefire to re-enter Government controlled areas. When she accompanied a group of people entering through the checkpoint at Parayanaalankulam on the Vavuniya-Mannar road there was an unexpected skirmish in which a grenade was flung at her. She was injured and lost blood. Her eyesight was impaired.

The British High Commission intervened and got her medically attended to at Vavuniya military hospital. After surgery she was flown out to Colombo and then out from the country. Her commitment to get the story out was such that Marie Colvin filed a despatch of 3,000 words to London from her hospital bed.

“One-eyed Jill”

It was the Sri Lankan incident that resulted in her losing an eye. She wore a black eye patch after that. It became her defining image and friends referred to her in lighter vein as “one-eyed Jill” as opposed to “one-eyed Jack” played by Marlon Brando.

Marie interacted with Sri Lanka again during the last days of the war in May 2009. She interviewed LTTE political wing head Nadesan on the phone and wrote an article about the pathetic predicament of entrapped civilians in the Mullivaaikkaal area.

She also played an “extra-journalistic role” in trying to help arrange the safe surrender of some senior LTTE personalities and around 2,000 civilians. She woke up the UN Chief of Staff, Vijay Nambiar at midnight and obtained an assurance from him on the matter. That characteristic humane effort by her proved unsuccessful in the end.

The life and work of Marie Colvin is multi-faceted and a manifestation of exemplary bravery and commitment. She spoke truth to power through her on the spot reporting of events that contradicted the official version.

Obituary in “Telegraph”

Her journalistic life and work was a remarkable saga worth recounting. Let me present therefore some excerpts from an obituary that appeared in the London Telegraph after her death.

Here are the

relevant excerpts:

“Marie Colvin did not put her life on the line to win acclaim. Instead it was by being in the line of fire, by sharing the risks of those she was writing about, that she was able to produce her immensely powerful coverage of conflict’s human toll.”

“She was doing precisely this when she was killed, telling the world of indiscriminate government shelling of “a city of cold, starving civilians”. Her eyewitness accounts were broadcast on CNN or the BBC because, though a staff reporter of more than 20 years’ standing for The Sunday Times, she was – as usual – the last journalist not to have fled.”

“Such dedication and proximity infused her coverage with emotion. In Syria, she said government forces were committing “murder” and she described how she had witnessed a baby die from shrapnel wounds. She was never mawkish, but nor was she minded to stand idly by and witness massacres.”

“In East Timor in 1999, for example, as Indonesian troops closed in on a United Nations compound in Dili where 1,500 people had taken shelter, the UN wanted to pull out and leave the refugees to their fate. Marie Colvin and two other female journalists remained in place, defying the UN, and the world, to do nothing.”

“Eventually, shamed by the courage of the reporters, Indonesian forces allowed the refugees to leave and the international community stepped in. Marie Colvin’s presence had undoubtedly helped save many hundreds of lives.”

“Marie Catherine Colvin was born on 12 January 1956 in Oyster Bay, New York, to William and Rosemarie Colvin, both schoolteachers. Marie, who attended Oyster Bay High school, studied American Literature at Yale, where she got her first taste of journalism by working for a university newspaper. After graduating she began her career in unorthodox fashion by taking a job on the in-house magazine of the Teamsters union.”

“Moving to the press agency UPI, she was appointed to its bureau in Trenton, New Jersey. Her urge above all, however, was to become a foreign correspondent. She swiftly convinced UPI to promote her to the Paris bureau, where her dash, good looks and dark curls soon won her a host of admirers.”

“Her break came in 1986, when she was in the Libyan capital, Tripoli, as America launched its biggest aerial attack since Vietnam. Filing copy while scrambling to avoid the explosions, she set a pattern that would last the rest of her career.”

“It was while there she was summoned to meet the Libyan dictator, Muammar Gaddafi, and over the next quarter of a century she frequently met him, as well as many other political leaders and despots. But a peculiar effect of her beguiling character and her journalistic talent was that tyrants were charmed by her, and sought her out, even as she eviscerated them in print. Last year she published an account of her encounters with the late Libyan leader over 25 years. It was entitled “Mad Dog and Me”.

“While in Libya in 1986 she began freelancing for The Sunday Times, which soon lured her over full time to become its Middle East correspondent. Her exploits quickly attracted the attention and envy of less bold colleagues – a broad category.”

“During the Iran-Iraq war, for instance, she smuggled herself in disguise into Basra, a city then completely closed off. In 1987 she reported from Bourj el Barajneh, the Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, which was under fire from the Syrian-backed Amal militia.”

“Marie Colvin herself reported from Kosovo, and freely admitted that she constantly weighed “bravery against bravado”. Around the turn of the century that balancing act took her closer to the edge than ever. First, in 1999, she scored her dramatic triumph in East Timor. Then, while the world was celebrating the new millennium, she appeared to have pushed things too far in Chechnya.”

“Based with Chechen rebels as Russian troops cut off all escape, she found that the only route out was a 12,000ft mountain pass to Georgia. During an eight-day midwinter journey she waded through chest-high snow and braved altitude sickness, hunger and exposure. Sunday Times colleague Jon Swain, helped organise a helicopter from the US embassy to pluck her off the mountainside to safety. As Marie Colvin wrote: “I was never happier to have an American passport.”

“She did not often require such assistance. And her time in Chechnya did not make her change her ways. Instead she was soon in Sri Lanka, as ever heading into rebel - this time Tamil Tiger - territory. As she tried to cross the front line back into government-held ground, she was hit by shrapnel in four places. Despite specialist surgery, she lost the use of her left eye and afterwards wore a patch.”

“She promised that she would take things easier. But that was always unlikely. And as the US-led invasion of Iraq triggered the most dramatic events in the Middle East for decades, remaining on the sidelines became impossible.”

“Soon she was back in the thick of things in Baghdad. There, as ever, she frayed editors’ nerves not only with her derring-do, but by filing her stories up to and far beyond deadline. Her copy was well worth waiting for, but the price to pay could be high.”

“Like many journalists who covered the Middle East, Marie Colvin welcomed the optimism of the Arab Spring. Though she knew that it would not affect an overnight transformation, she was compelled to see it through; where cynicism had blunted the determination of so many of her contemporaries, she remained unwearied. Agonizingly, for those who knew and loved her, however, that meant the nature of her death had a certain inevitability about it.”

“Marie Colvin, of course, did not see it that way. She loved life, and brought an American exuberance to the countless parties she graced over many years”

Why do journalists risk danger?

The “Telegraph” obituary sums up the essence of Marie Colvin’s life and times but I want to conclude by posing the question – “Why do journalists risk danger and even lives by doing what they do”. Why do war correspondents undergo such hazards to get the “story” or picture?

I want to let Marie Colvin herself answer it by reproducing an address by her in November 2010. It was at St. Brides Church in London at a special service of Thanksgiving and remembrance for all journalists and staff who passed away in the line of duty in war zones.

Here are a few excerpts from

her address:

“I am honoured and humbled to be speaking to you at this service tonight to remember the journalists and their support staff who gave their lives to report from the war zones of the 21st Century. I have been a war correspondent for most of my professional life. It has always been a hard calling. But the need for front line, objective reporting has never been more compelling.”

“Despite all the videos you see from the Ministry of Defence or the Pentagon, and all the sanitised language describing smart bombs and pinpoint strikes, the scene on the ground has remained remarkably the same for hundreds of years. Craters. Burned houses. Mutilated bodies. Women weeping for children and husbands. Men for their wives, mother’s children.”

“Our mission is to report these horrors of war with accuracy and without prejudice. We always have to ask ourselves whether the level of risk is worth the story. What is bravery, and what is bravado?”

“I lost my eye in an ambush in the Sri Lankan civil war. I had gone to the northern Tamil area from which journalists were banned and found an unreported humanitarian disaster. As I was smuggled back across the internal border, a soldier launched a grenade at me and the shrapnel sliced into my face and chest. He knew what he was doing.”

“Many of you here must have asked yourselves, or be asking yourselves now, is it worth the cost in lives, heartbreak, loss? Can we really make a difference?”

“I faced that question when I was injured. In fact one paper ran a headline saying, has Marie Colvin gone too far this time? My answer then, and now, was that it is worth it.”

“We go to remote war zones to report what is happening. The public have a right to know what our government, and our armed forces, are doing in our name. Our mission is to speak the truth to power. We send home that first rough draft of history. We can and do make a difference in exposing the horrors of war and especially the atrocities that befall civilians.”

Journalists do make a difference

“The history of our profession is one to be proud of. The real difficulty is having enough faith in humanity to believe that enough people be they government, military or the man on the street, will care when your file reaches the printed page, the website or the TV screen. We do have that faith because we believe we do make a difference.”

(The writer can be reached at [email protected].)