Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Saturday, 6 April 2024 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

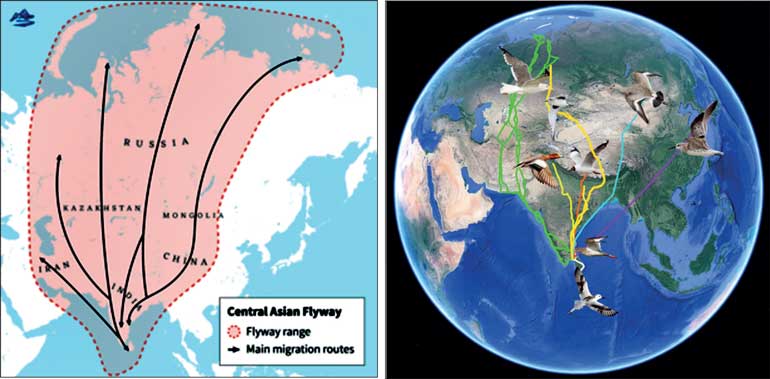

Figure 1 – Central Asian Flyway

Background

Background

A wind farm consisting of 30 towers generating 100MW (Phase 1 – Thambapawani) was established on the southern coast of Mannar Island in 2020, with financial assistance from the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The widespread criticism of this project due to its positioning within one of the main bird migratory corridors in the Asian region (detailed elsewhere in the article) was largely overlooked or ignored due to the economic priorities that prevailed at the time, as it happened with the now infamous Canadian-funded Sinharaja Mechanised Logging Project of the 1960s and 70s.

During Sri Lanka’s worst health and economic crises in recent times, the billionaire Indian businessman Gautham Adani visited Sri Lanka and met with the then President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa followed by a visit to the proposed renewable energy project site in Mannar on a Sri Lankan Air Force Helicopter. Subsequently, the Ministry of Power and Energy, Sri Lanka agreed to receive an unsolicited proposal for awarding the construction and operation of the Mannar Wind Power Project (Phase-II) and another in Poonaryn to Adani Green Energy Sri Lanka Ltd. (AGESL), as Build, Own, and Operate (BOO) projects for a period of 25 years for an approximate investment of $ 500 million.

The proposed Mannar Wind Power Project (Phase-II) has a capacity of 250 MW and comprises 52 wind turbines of 5.2 MW capacity each. These are to be placed in parallel with the existing Thambapawani wind farm spreading across most parts of Mannar Island. The project is expected to generate 1048 GWh of energy annually. The Annual Energy Production (AEP) of the proposed wind farm is around 6% of the country’s energy requirement.

Ecological significance of Mannar Island

Mannar Island and other islands on the Gulf of Mannar spanning India and Sri Lanka have been identified as among the most important migratory corridors and a Critical Wintering Site for bird species in the Central Asian Flyway. The ecological significance of Mannar and the wider Gulf of Mannar for the Central Asian Flyway is recognised by Birdlife International (Important Bird and Biodiversity Area, and Key Biodiversity Area), Wetlands International (Critical Site Network 2.0), and the Ramsar Convention (Vankalei Sanctuary is a Ramsar Wetland), as well as by the Government of Sri Lanka, which has declared three Protected Areas covering Mannar’s key wetlands, namely, Adam’s Bridge National Park, Vankalei Sanctuary, and the Vidataltivu Nature Reserve.

It also provides breeding habitats for eight species of seabirds, many of which are listed as Critically Endangered (CR) in the national Red List of Threatened Species. Sri Lanka, being a signatory nation to the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) has committed to safeguarding these migratory species.

Furthermore, Sri Lanka is a signatory nation for the United Nations Convention of Migratory Species (CMS). Hence, we have a global responsibility and binding to protect about 15 million birds (of 250 species) visiting Sri Lanka from over 30 countries. Mannar alone gets about a million birds representing 150 species. There are clear evidence-based reports that Mannar Island provides overwintering ground and breeding habitats for numerous seabirds, waterbirds, and forest birds, some of which are classified as Critically Endangered in Sri Lanka’s national Red List of Threatened Species.

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and its deficiencies

The EIA for this proposed 250 MW Mannar Wind Power Project (Phase II) was submitted to the Sri Lanka Sustainable Energy Authority in January 2024 by the Consulting Engineers & Architects Ltd. It was then made open for public review for 30 working days from 23.01.2024 to 06.03.2024 and is currently available on the web. (03.115.26.10/2023/EIA/Mannar%20Wind%20Power%20Project%20Phase%20II%20EIA%20Final%20-%20English.pdf).

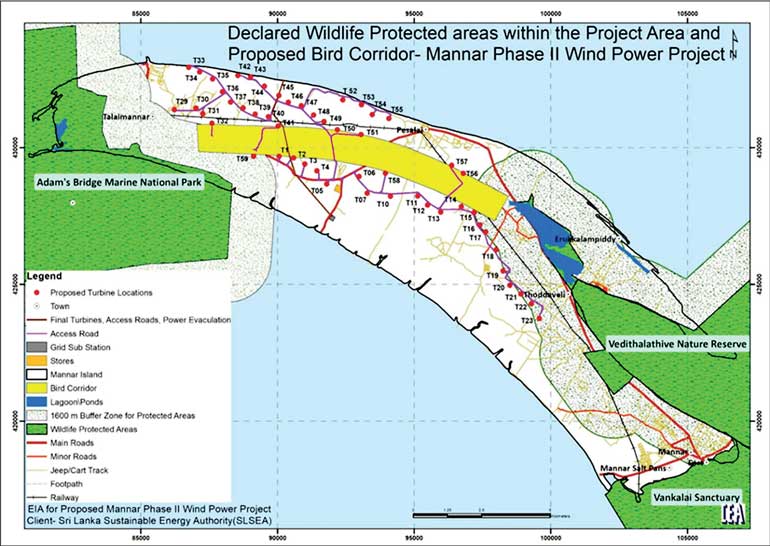

Figure 2 – Mannar Island surrounded by protected areas

Public opinion is beginning to appear in mass media about the conduct as well as on the findings of the EIA since it was made available on the web creating headlines, raising eyebrows, and causing much controversy. Public comments received during this period have now been collated and submitted by the CEA to the Sri Lanka Sustainable Energy Authority (SLSEA) for technical assessment and response. The CEA is expected in turn to undertake a technical review of the project’s environmental conformity under the National Environment Act.

This project reminds us of the controversies generated during the Sinharaja Logging Project around the 1970s where an overambitious project proposal prepared by the State Timber Corporation proposed to selectively log the Sinharaja Forest Reserve and the surrounding forests for the supply of peeler logs for the manufacture of plywood. This supply of plywood would be used for making tea chests to facilitate the export of tea – a mainstay of the Sri Lankan economy. The strong public opinion mounted within as well as outside the country against this logging project compelled the then Government to appoint a ministerial committee to report on the veracity of the public criticism and make recommendations on the continuation of the project.

The George Rajapaksa Committee reported that the logging project was unsuitable for the fragile terrain leading to excessive environmental (including biodiversity) damage, and insignificant benefits to local people, gross overestimate of its timber potential leading to literally creaming off Sinharaja and other forests in a 20-year vicious cycle. This project became an election issue at the 1977 general election and with the change of Governments, one of the first things that the newly elected prime minister did was to suspend the Sinharaja Logging Project. Interestingly enough, there are several parallels between the Sinharaja logging project and this wind power project which I intend to refer to at appropriate places.

In this review, I intend to bring together different viewpoints expressed by environmentalists, scientists, and some energy experts alike and suggest a way forward in addressing this environment/energy conundrum.

Environmental impacts

The environmental activists solidly backed by evidence-based scientific information are intensifying their campaign against the proposed Adani wind farm in the Mannar Island. They have accused the Sri Lankan political parties of having ignored the disastrous environmental, social, and economic implications of the Adani wind farm to be established in Mannar.

According to environmental critics, this newly proposed Wind Power Project (Phase II) poses an even greater risk to the Mannar region than the Phase I Thambapavani project. 52 huge wind turbines are to be spread across most of the island, covering the entire northern half that is lodged among the most important migratory corridors for species in the Central Asian Flyway viz. Adam’s Bridge National Park, Vankalei Sanctuary (a Ramsar Wetland Site), and the Vidataltivu Nature Reserve (Figure 2).

Among the critics of the international conservation agencies, Martin Harper, Chief Executive Officer, Birdlife International writing to the President of Sri Lanka says, “Your wonderful country is situated at the southernmost tip of the Indian Subcontinent in the Central Asian Flyway, serving as a crucial over-wintering ground for an estimated 15 million birds, representing 250 species, migrating across 30 countries, from the Russian Far East to eastern Europe through South Asia. Sri Lanka, being a signatory nation to the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) has committed to safeguarding these migratory species.”

Martin Harper goes into say in his three-page letter to President Ranil Wickremesinghe that Birdlife International along with FOGSL and their colleagues in the research community stands ready to support Sri Lanka’s energy sector in identifying nature-safe siting options, such that Sri Lanka can meet its energy needs in an ecologically sensitive manner.

The EIA report, according to these critics, fails to adequately address the project’s impact on migratory birds due to,

i) inadequate timing and seasonality

of bird observations,

ii) outdated methodologies used,

iii) negligence regarding international

conventions and scientific literature,

iv) Moreover, the proposed project’s location neglects alternative sites with high wind energy potential and lower

ecological impact.

It is clear from these that the potential ecological and economic repercussions of the project extend beyond Mannar Island, affecting bird tourism across Sri Lanka and hindering its burgeoning eco-tourism prospects while posing a great risk to migrants of the Central Asian Flyway.

The narrow ‘movement corridor’ (marked as a yellow band in the map given in the EIA Report) for millions of migratory birds proposed by the EIA seems highly arbitrary and lacks support from currently available information in the EIA report, itself. The corridor is proposed conveniently away from the proposed wind farm based apparently on – no study and no data!

Chris Goodie, Chairman of the Oriental Bird Club urges a comprehensive review of the project and careful adjustment of the project location and requests the Sri Lankan Government to identify ecologically safe zones for such renewable energy projects, guided by Strategic Ecological Assessments (SEA) and globally available tools like AVISTEP (The Avian Sensitivity Tool for Energy Planning). This would ensure that Sri Lanka would meet its vital energy demand while safeguarding its critical birdlife and, more importantly, without compromising the ecological and economic benefits for the citizens of the country.

Rohan Pethiyagoda, an internationally renowned biologist and a leading environmental activist in Sri Lanka claims that the Government must have an open and transparent bidding process for projects of this magnitude. The EIA doesn’t provide a socioeconomic cost-benefit analysis or any rational evaluation of alternative sites. In terms of the EIA process, it is incumbent on the proponent to demonstrate that they have looked at alternative sites and selected the one with the lowest impact. As it stands, he slams the EIA as just a whitewash.

Pethiyagoda goes on further to argue that the EIA is obliged to consider sites at which the impact could be lower, but it has failed to do so. For example, he reasons out why this project cannot be located in a nearby less environmentally sensitive location such as Seelavatturai, Kondachchi, Arippu, or even Kalpitiya. Where is the cost-benefit analysis, or the evaluation of alternative sites, he asks. Multiple sites need to be evaluated and choose the one with the lowest environmental impact and greatest socio-economic benefits.

Likewise, the senior environmental lawyer Dr. Jagath Gunawardana also stresses this deficiency of the EIA. According to him, “In our preliminary observations, we have found that they have not adhered to the basic requirements of an EIA, not having looked at alternatives to the project in a meaningful manner as required under Section 33 of the National Environment Act. THEREFORE, THERE IS A CLEAR COURSE OF LEGAL ACTION AVAILABLE TO ANY PARTY IN SRI LANKA.”

He goes on to say that the Sustainable Energy Authority had prepared a document on wind-power generation, where they had identified locations in seven districts as areas with high potential for wind-power generation and Mannar is not one of them. The island of Mannar has areas that have medium and lower potential. Ironically, the area is claimed to have valuable mineral resources and nearby offshore gas and oil fields of proven economic value.

It is quite clear from the above critiques that the ecological repercussions as a direct result of these ad hoc developments in Mannar are expected to severely impact the region’s economy and the potential for wildlife-based tourism planned by the Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority and Northern Development Framework much the same way as it happened with the Sinharaja Logging Project in the 1970s.

The energy experts, on the other hand, counterargue that since Mannar already has an existing wind power plant (Thambapavani) which was established after a thorough vetting process of an EIA, preparing an EIA for the second phase of the project is only a formality and that there ideally shouldn’t be any concerns since the EIA of the first phase of the project has given green light to the establishing of wind power plants in Mannar.

However, the environmental impacts pointed out by knowledgeable people have largely been ignored in the Thambapawani (Phase I) project EIA. Any lessons learned since its implementation have been overlooked in the AGESL (Phase II) project EIA although it claims that certain negative impacts on the local environment, and mitigation measures to overcome them were identified for the EIA study and valued (P 17-EIA Summary).

Moreover, the proposed project’s location neglects alternative sites with high wind energy potential and lower ecological impact with a satisfactory benefit-cost analysis.

World Bank off-shore wind power roadmap for Sri Lanka as a viable alternative?

World Bank off-shore wind power roadmap for Sri Lanka as a viable alternative?

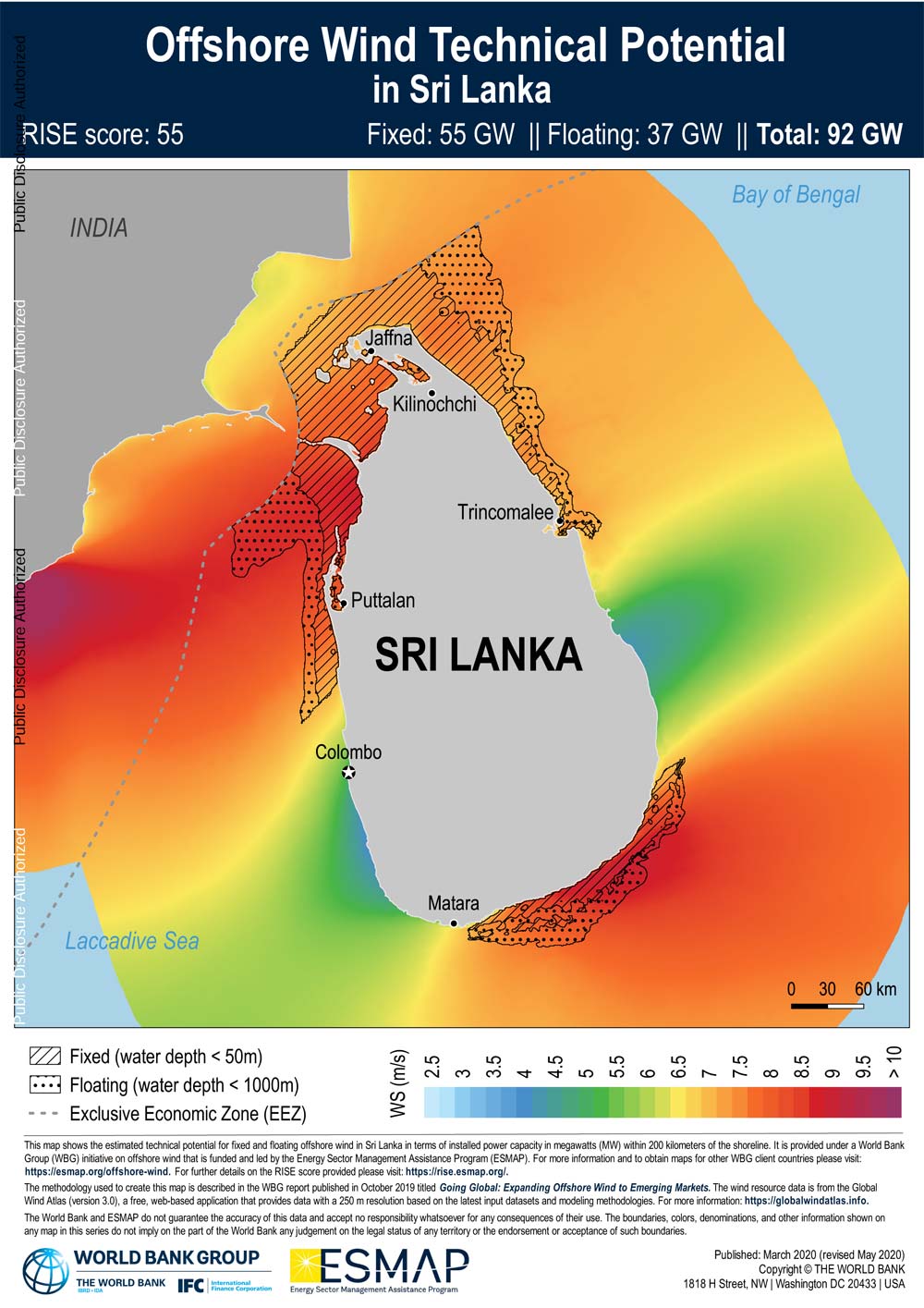

According to a roadmap developed with the assistance of the World Bank (WB) and International Finance Corporation in 2023, Sri Lanka has good conditions for offshore wind, with most of the more than 50 GigaWatts of potential being held in the western and southern coasts, with a caveat that the roadmap analysis found that not all of this potential will be developed due to practical and cost limitations that are prevailing at present.

According to World Bank, Sri Lanka’s offshore wind resource far exceeds its energy demand, and its development could help the country’s economic recovery by displacing costly fuel imports. There is an estimated fixed-bottom potential of 22GW and 17GW floating. Most importantly, unlike the on-shore Mannar Wind Farm, this off-shore resource is based in areas without environmental restrictions and exclusion zones. Areas with the highest environmental or social sensitivities have been excluded to avoid unacceptable adverse impacts. Indeed, the World Bank reckons there is huge potential, and it could supply more energy than the country needs – offering an opportunity to produce other fuels, such as hydrogen

and ammonia.

However, there are numerous challenges to developing this sector, according to the WB Report. To overcome these challenges, the World Bank Group was assisting the Government in planning and implementing de-risking measures, including further site investigations, environmental and social scoping, wind resource assessment, legal and regulatory analysis, further stakeholder consultations, and policy support to make this opportunity more attractive to investors and help to reduce costs.

The World Bank Report further says that considering that the short- and medium-term trajectory for offshore wind in Sri Lanka is relatively modest, combining the opportunity with India’s growing offshore wind market could help attract more industry and supply chain investment. The message given is to partner with India for the development of offshore wind energy generation instead of developing environmentally costly onshore wind farms in Mannar Island.

The energy experts, however, claim that the Mannar Wind Farm Project is a low-hanging fruit the country should pluck. Yet, they do not seem to have given adequate recognition to the environmental costs involved in the same way as in the case of the Sinharaja Logging Project more than 50 years ago. The field of Environmental Economics has advanced substantially over the last several decades. As Chris Goodie, Chairman of the Oriental Bird Club advocates, globally available tools like AVISTEP (The Avian Sensitivity Tool for Energy Planning) need to be used to identify ecologically safe zones for such renewable energy projects.

Moreover, there are widely used open-source environmental economics software packages such as InVEST (Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs) which provide an effective tool for balancing the environmental and economic goals of these diverse entities. It enables decision-makers to assess quantified tradeoffs associated with alternative management choices and to identify areas where investment in natural capital can enhance human development and conservation.

It is not clear whether the EIA for this project has meaningfully addressed the environmental cost-benefits issues. If those could be brought into the equation, it would ensure that Sri Lanka would meet its vital energy demand while safeguarding its critical birdlife and, more importantly, without compromising the ecological and economic benefits for the citizens of the country.

Resource economic analysis

The activists point out how, if the permission is granted and the project continues, Sri Lanka will have to pay way above the market rate for a single unit of energy in US Dollars. In Adani Wind Power Project, the energy agreement duration is believed to be 25 years and throughout that period, it is alleged that Sri Lanka will have to pay 4 US cents, as opposed to 2 US cents which is the market price for a single unit. In a nutshell, for 25 years, Sri Lanka will have to buy power, generated via natural resources of our own, from India for double the price.

This wind power project is an unsolicited project decided according to the whims of politicians probably under duress during the recent health and economic crises. Engineer Pethiyagoda very eloquently remarks on this issue: “We see a foreign company coming to Sri Lanka literally out of the blue, harnessing our wind energy, which is a sovereign national resource, and then selling it back to us for foreign currency over a fixed 25-year contract. How does this make economic sense? If the government called for bids from local companies, Sri Lankan shareholders would have had a chance to invest. That way we don’t bleed foreign currency, and what’s more, there’s tax revenue as well. What is the logic in giving this on a platter to a foreign company?

“In that case, let them prove it by actually competing in a transparent bidding process. Besides, even the price they have quoted, of USD 0.097 per kilowatt hour is several times the wind energy price obtained in the USA, according to the US Department of Energy. They are making a massive profit on this, and Sri Lankans will have to foot the bill for the whole of the 25-year contract period.”

While both, the conversion to renewable energy as well as ecological conservation are both important targets to achieve, ultimately the decision would come down to proper weighing of the economic and ecological costs and benefits.

Sri Lankan environmental groups are intensifying their campaign against the proposed Adani wind farm in Mannar. They have accused the Sri Lankan political parties of having ignored the disastrous environmental, social, and economic implications of the Adani wind farm to be established in Mannar.

Mannar Island and its environs – a ‘living entity’ and a classic case for environmental jurisprudential analysis?

Many countries the world over are now beginning to confer the status of a legal entity to ‘Mother Nature’ recognising her as a ‘living being’. In that sense Nature too has its own rights comparable to those of human rights. In 2017, the High Court of Uttarakhand at Nainital in India stated that the Ganga and Yamuna Rivers are legal and living persons. In 2019, the High Court Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh recognised all rivers in the country as living entities with legal personalities. In Brazil in 2017, the Bonito City Council amended Article 236 of the Lei Orgânica No. 01/2017 to recognise nature’s right to exist, prosper and evolve.

A staff writer of ‘The Hindu’ newspaper reported in 2022 that Justice S. Srimathy of the Madurai Bench of Madras High Court invoked the ‘parens patriae jurisdiction’ and declared ‘Mother Nature’ as a ‘living being’ having the status of a legal entity. The court observed that ‘Mother Nature’ was accorded rights akin to fundamental rights, legal rights, and constitutional rights for its survival, safety, sustenance, and resurgence to maintain its status and also to promote its health and well-being. The State and Central governments are directed to protect ‘Mother Nature’ and take appropriate steps in this regard in all possible ways.”

The Mannar Island surrounded by several environmentally buffered sanctuaries serves as a strong candidate to be considered as a ‘living entity’ and develop the necessary legal infrastructure for establishing the status of a legal entity in order to confer ‘rights akin to fundamental rights, legal rights, constitutional rights for the survival of the natural wealth of the Mannar Island and its safety, sustenance. As Dr. Jagath Gunawardena points out, there is a clear case for legal action under Section 33 of the National Environment Act This can be coupled together with a case for a ‘living entity’ taking a cue from other countries including those from India.

It is quite intriguing that on the one hand, Sri Lankan rainforests are among the progenitors from which the vast expanses of Southeast Asian rainforests evolved and diversified. On the other hand, Mannar Island and its surrounding areas have evolved as converging regions of millions of birds of European and Asian continental origin. Thus, both the Sri Lankan rain forests and the Mannar Asian flyway merit to be considered equally as living entities.

Other successful public campaigns on nationally important projects

In addition to the Sinharaja logging project, I can recall at least two other potentially harmful – (environmentally, socially, and economically) projects where strong and well-substantiated scientific (and strong trade union-) actions prevailed successfully over nationally detrimental projects.

One was the FINNIDA and IDA-funded Forestry Master Plan of 1982. The project proponents eventually yielded to the strong and credible criticisms mounted on this project by the scientific and environmentally conscious community. A public seminar was held to present both for and against viewpoints and the presentations were published in a booklet published by the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka in 1988.

The international funders highly sensitive to the rationally presented negative sentiments expressed by the scientists, withdrew the project document and a far more acceptable Forestry Sector Master Plan was published in 1995 with almost 10 years of extensive studies on every conceivable activity related to the forestry sector including the formulation of a revised ‘Forestry Policy’ which is being used even today with its current revision.

The second is yet another low-hanging bitter-sweet fruit like the proposed Mannar Wind farm which was initially agreed by the Sri Lankan Government to hand over the part-completed Eastern Terminal of the Colombo port on a long-term lease to the same Adani Group. This time, the strong trade unions backed by their technocrats swung into action to highlight what Sri Lanka would be losing on this deal and forced the Government to reconsider its former pledge and persuade the Adani group to accept an alternative site – the Western terminal. The economic and social benefits of this project to Sri Lanka are yet to be seen and commented upon by economists.

A challenge to the patriotic citizens, diasporic community, and well-wishers of Sri Lanka

As it happened in the case of the Sinharaja Logging Project in early 1977, a plethora of viewpoints both for and against the Mannar Wind Farm Project are peaking at a time when Sri Lankans are at the doorstep of a national election – presidential or otherwise. This provides an excellent platform for both in-country and diasporic technocrats/intelligentsia as well as others who are sympathetic to Sri Lanka’s current crisis and concerned about long-term sustainability to contribute their expert knowledge on this nationally important issue which has the potential to become a political issue in this election year, just like the Sinharaja logging project 50 years ago.

Politicians of different hues and colours could in turn be exhorted to express their standpoints on evidence-based information on this far-reaching issue of national significance preferably circumventing without caving into superpower hegemony. In this regard, the diasporic community in countries where they have had the opportunity to meet their favourite politicians in recent times have a role to advise their masters’ on how to tread on these political landmines. It indeed will help the intelligent voters at home to make their own decisions on the credibility of the Sri Lankan political fraternity.

The patriotic in-country and diasporic community are given a last chance to advise their political masters in this election year, a comparative cost-benefit analysis of i.) the hastily prepared and inadequately evaluated on-shore economically sweet low-hanging fruit against ii.) a better prepared environmentally-, socially and economically (over the long term) bitter-sweet fruit.

In my layman’s opinion as a renewable energy enthusiast, this merits a rare opportunity for the scientists (environmental- social-politico-legal, etc.) and technocrats interested in seeing Sri Lanka coming out of the woods during this critical period to express their candid views supported by scientific evidence in the form of a pilot study.

Unlike at the time of the Sinharaja Logging Project, there are far more resources available to model different scenarios/trajectories leading up to 2048 – the year that the President of Sri Lanka has targeted for a complete economic recovery.

In the 1970s, the strong public outcries saved the endemic and threatened trees of Sinharaja being made into plywood boxes to export tea. Paper cartons emerged as an excellent alternative source of packaging tea for exports. In the same manner, we hope that the Mannar Island on-shore wind farms will be relocated to environmentally friendlier off-shore and alternative on-shore locations.

The on-shore low-hanging sweet fruit with a bitter seed inside providing only 6% of the country’s energy requirement vs. the off-shore resource-based sweeter fruits still ripening in the difficult-to-reach higher branches – so to speak – and most importantly designated to be located in areas without environmental restrictions and exclusion zones with the potential of supplying more energy than the country needs (in addition, offering an opportunity to produce other fuels, such as hydrogen and ammonia) as per World Bank ‘Windfall’ Road Map should indeed become an intriguing scientific, socio-economic and politico-legal battle in this year preparing for national elections.

(The writer works at University of Peradeniya.)