Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 12 September 2025 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

If Kinross is a warning, we are ignoring it at our peril

For generations, Kinross Beach was more than just a stretch of sand; it was the vibrant heart of a community. It was the training ground for national athletes, the backdrop for countless family picnics, and the stage for sporting legends. It represented a shared public space where memory and community were forged, a testament to the simple, enduring joy of our coastal heritage. Yet, today, the ghosts of this arcadian past are swallowed by a desolate present, a mere rusting skeleton of what it once was. The once-vibrant shoreline is now a casualty of an unnatural disaster, a man-made waterloo that serves as a chilling indictment of civic neglect and corporate greed.

For generations, Kinross Beach was more than just a stretch of sand; it was the vibrant heart of a community. It was the training ground for national athletes, the backdrop for countless family picnics, and the stage for sporting legends. It represented a shared public space where memory and community were forged, a testament to the simple, enduring joy of our coastal heritage. Yet, today, the ghosts of this arcadian past are swallowed by a desolate present, a mere rusting skeleton of what it once was. The once-vibrant shoreline is now a casualty of an unnatural disaster, a man-made waterloo that serves as a chilling indictment of civic neglect and corporate greed.

There was a time when Colombo’s Kinross Beach was not just a stretch of coastline but a living part of the city’s identity. The mornings were filled with the whistle of sea breezes and the shouts of swimmers as they cut through the surf. Families strolled along the sand, vendors sold tea and snacks, and young men and women trained in swimming and lifesaving under the watchful eye of their mentors. I still remember the feel of that sand under my feet, running athletic drills as the sun rose over the city, the sea breeze cooled my skin. It was a place where we mastered our skills, forged friendships, and built memories that shaped who we were.

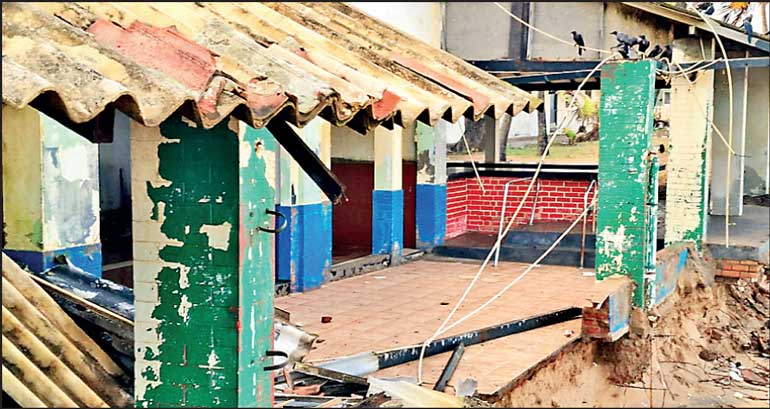

Today, that golden expanse has been reduced to a narrow strip of eroded shoreline, lashed daily by waves and littered with the fragments of neglect — plastic bottles, torn wrappers, and even French-letters, all strewn carelessly where children once played. The most haunting sight is the fishing trawler, stranded years ago, now a rusting skeleton baking under the scorching sun. It has become an accidental monument to inaction, an unspoken reminder of how quickly we let our shared spaces decay. But make no mistake — this is no act of nature alone. It is a man-made catastrophe.

Urgent alarms

Reports warning of this disaster been gathering dust for decades. The Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Department has published at least four major studies since 1997 predicting severe erosion along the Colombo oceanfront if unregulated sand mining and haphazard construction continued. The Central Environmental Authority’s 2013 Environmental Impact Assessment on Colombo’s coastal belt flagged multiple risks tied to hotel construction, illegal structures, and the blocking of natural sand flow. These were not vague suggestions — they were urgent alarms. Yet the recommendations were ignored, underfunded, or quietly shelved in favour of short-term commercial interests.

The Marine Environment Protection Authority, tasked with safeguarding these waters, has done little more than issue press releases after each environmental mishap.

The Kinross Swimming and Life Saving Club has a history worth remembering — and worth fighting for. It was born out of tragedy in 1941 after a spate of drowning incidents highlighted the urgent need for organised water safety. The vision came from Guy Thiedeman, a champion athlete and lifesaver who proposed creating a safe bathing area. But it was Mike Sirimanne — along with his friends Herbert Pathiwela, Elmo and Lou Spittel, Anton Selvam, Ron Kellar, Basil Misso, and Hugh Stewart — who turned vision into reality. These men were pioneers.

They trained under Thiedeman and later under Australian surf lifesaver Harry Nightingale, who introduced modern life-saving methods to Sri Lanka. With their own hands, they built the club’s first headquarters — a humble shack on the beach — a symbol of civic spirit and community action. By 1955, a more permanent clubhouse was erected, and Kinross became a beacon for swimming, lifesaving, and beach recreation in Colombo. For decades, it produced skilled lifesavers who patrolled the beaches and saved countless lives. The club’s founders believed in a simple truth: the beach belonged to the people. It was a place to be enjoyed, protected, and respected. The loss of that beach is not just a physical erosion — it is the erosion of the very ideals on which Kinross was built.

Warnings of irreversible damage

Meanwhile, committee after committee was formed to “study” the issue. The Presidential Task Force on Coastal Zone Management in 2016, the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency’s (NARA) 2018 sediment transport study, and the Coast Conservation Department’s own Coastal Zone Management Plan for 2019–2023 all warned of irreversible damage if mitigation efforts were delayed. Instead of decisive action, what followed were half-hearted rock dumping projects that simply shifted the problem down shore, exposing Wellawatte and Dehiwala to even greater wave energy. Committee members signed off on permits for private developers to build right up to the high-water mark, narrowing the natural buffer zone.

This is not administrative failure; it is collusion. It is time we start naming those responsible — the coastal engineers who approved illegal structures, the environmental officers who looked away, and the politicians who pocketed campaign donations from the very firms dredging our sand for profit. Accountability must be personal, not abstract. A few token “beach nourishment” projects every five years are not solutions; they are photo opportunities.

The consequences of inaction go beyond lost beaches. The Colombo–Galle railway line, hugging the eroding coastline, is increasingly at risk. Each meter of lost sand brings the tracks closer to collapse. Already, authorities are forced to slow trains or suspend services during high tides, causing widespread disruption. Marine Drive, celebrated as a solution to Colombo’s traffic congestion, is now an exposed, vulnerable strip that could be underwater within decades if present trends continue. The government spends billions on expressways, but cannot protect the most basic public spaces for its citizens.

The erosion of Kinross Beach is not an act of nature but a consequence of a system mired in bureaucratic inertia and what can only be described as a studied indifference. For years, the warnings were clear and unequivocal. Multiple Government reports, commissioned at taxpayer expense, meticulously documented the encroaching threat and proposed concrete solutions.

These recommendations, however, were methodically shelved, their findings allowed to gather dust while the tides of destruction advanced unimpeded. This history of ignored advice exposes a disturbing pattern of official negligence, where the short-term gains of a select few were prioritised over the long-term well-being of the public. The tragedy of Kinross is not a simple case of incompetence but a systemic failure that speaks to a deeper collusion between those in power and those who profit from public decay.

Eroding not just our coastline but our civic trust

The narrative of Kinross Beach extends far beyond its eroding shoreline. It is a metaphor for the broader, creeping threats against our public infrastructure. The same destructive forces that are consuming our beach now imperil the very foundations of our coastal city, from the historic Colombo–Galle railway to the vital Marine Drive. The fate of one is inextricably linked to the fate of the other. The deliberate inaction that allowed Kinross to crumble is the same apathy that will one day leave our critical infrastructure vulnerable to collapse, eroding not just our coastline but our civic trust and shared national values.

To reverse this course, we must move beyond lament and demand accountability. The restoration of Kinross is not merely a local project; it is a national commitment. We must hold those responsible for this dereliction of duty to account, and we must insist on a future where public assets are preserved with the diligence they deserve. The fate of Kinross Beach stands as a stark warning and a profound challenge: will we allow this man-made destruction to stand as a monument to our collective neglect, or will we unite to reclaim our shared spaces and restore the promise of our public trust?

If Kinross is a warning, we are ignoring it at our peril. Sri Lanka’s coastline is more than just a tourist attraction; it is a vital economic and cultural asset. Its loss would not just affect commuters and tourists but entire communities who depend on fishing, recreation, and tourism for their livelihoods. We cannot afford to keep responding with short-term, piecemeal fixes. We need a national commitment to audit and expose every decision made by coastal management committees that worsened erosion. We need to hold individuals accountable, not just institutions, for negligence and complicity. We must restore natural defences — mangroves, dunes, and reefs — rather than relying solely on concrete and boulders. Waste management must be overhauled, and a nationwide campaign launched to end littering on beaches. Development must be planned intelligently, with foresight and community benefit at the heart of every project.

The waves will not wait for committee meetings. The sea is advancing every day, taking with it not just sand but our history, our culture, and our shared spaces. Kinross was a place where we learned to respect the ocean — to swim with it, not against it. Today, it stands as a testament to what happens when we abandon that respect. This is not simply about saving a beach. It is about saving the very ground beneath our feet — the spaces that make Sri Lanka liveable, beautiful, and whole. If we continue to let complacency, corruption, and complicity govern our response, we will wake up one morning to find not just our beaches gone, but the railway, the livelihoods, and the trust in our public institutions washed away with them. The ocean is not the enemy. Our failure to act is.