Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Friday, 13 February 2026 00:18 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The author has recently returned from his Antarctic Expedition and penned this article reflecting on his executive leadership education at the University of Minnesota and Harvard University

The author has recently returned from his Antarctic Expedition and penned this article reflecting on his executive leadership education at the University of Minnesota and Harvard University

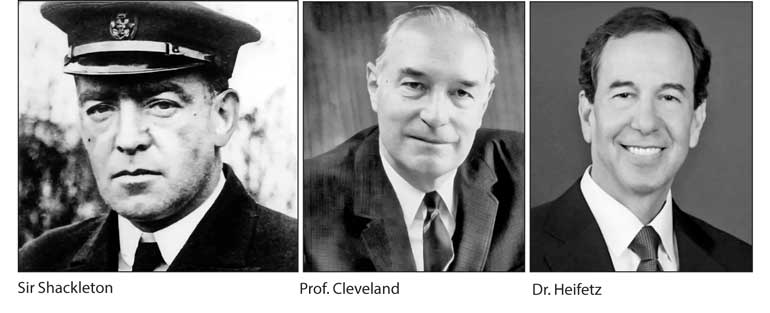

In 1915, Sir Ernest Shackleton stood on the frozen graveyard of the Weddell Sea and watched as his ship—Endurance—was crushed by ice like a walnut. In that moment, Shackleton did not just lose his vessel; he lost his mission to achieve the first trans-Antarctic crossing of the white continent.

For most, this would be the end of the story. For the rest, Shackleton’s legendary Antarctic expedition marked the beginning of a masterclass in leadership that remains the gold standard for our fractured, complex geopolitical landscape in 2026.

Having just returned from the Antarctic—where the wind still carries the ghost of Shackleton’s “unwavering optimism”—I could not help but think every night about the inescapable parallels to our modern world. Today’s leaders are not battling icebergs, but they are navigating a “nobody-in-charge” society. This phrase was coined by the legendary late US diplomat and educator Harlan Cleveland, who was my mentor for more than a quarter-century at the University of Minnesota and beyond.

In a world of evolving conspiracies and lies, where information is our dominant resource and old hierarchies are melting away, the lessons of the South Pole—filtered through the frameworks of Professor Cleveland and my Harvard University professor on leadership, Ronald Heifetz—offer a vital survival guide for the 21st-century executive.

The adaptive pivot: From the dance floor to the balcony

When the Endurance sank, Shackleton did not double down on his original mission to cross the inhospitable coldest desert. Instead, he performed what Professor Heifetz calls the ultimate “adaptive pivot.” Shackleton realised that he was no longer facing a technical problem (how to sail a ship), but rather an adaptive challenge: shifting the hearts and minds of 27 men from being trans-Antarctic “explorers” to “survivors” in a hopeless environment.

When the Endurance sank, Shackleton did not double down on his original mission to cross the inhospitable coldest desert. Instead, he performed what Professor Heifetz calls the ultimate “adaptive pivot.” Shackleton realised that he was no longer facing a technical problem (how to sail a ship), but rather an adaptive challenge: shifting the hearts and minds of 27 men from being trans-Antarctic “explorers” to “survivors” in a hopeless environment.

Heifetz, whose innovative work at the Harvard Kennedy School remains vital in 2026, argues that true leadership requires stepping away from the “dance floor”—the daily chaos—and onto the “balcony” to view the entire system and its evolving behavioral patterns. Shackleton did exactly this. He stepped back to assess the “temperature” of his crew, identifying who was cracking and who was resilient. He then “gave the work back” to his men, making every sailor responsible for the group’s collective survival.

To regulate their stress, Shackleton employed routines and humor, ensuring the group did not “blow up” under the pressure of Antarctic isolation. He knew that despair was a greater threat than the chilling cold. By practicing Cleveland’s “genuine interest in others,” Shackleton invited the grumblers into his own tent to understand what they thought and why, ensuring that no “sub-zero gossip” could sink the team’s morale and optimism.

Of course, today’s leader may not literally be stranded on an iceberg. But in our “nobody-in-charge” society, the ice is always shifting. To lead in an interconnected global community, one must combine Shackleton’s grit with Cleveland’s integrative thinking and Heifetz’s systemic perspective.

The “Get-it-All-Together” profession

Shackleton’s brilliance lay in what NATO Ambassador Cleveland called “integrative thinking.” The ambassador viewed leadership as the “get-it-all-together profession.” Thus, a perceptive leader must develop a “generalist mindset”—the antidote to siloed organisational thinking. In our era of hyper-specialisation and automation, the leader’s role is to weave disparate parts into a cohesive whole.

Shackleton’s brilliance lay in what NATO Ambassador Cleveland called “integrative thinking.” The ambassador viewed leadership as the “get-it-all-together profession.” Thus, a perceptive leader must develop a “generalist mindset”—the antidote to siloed organisational thinking. In our era of hyper-specialisation and automation, the leader’s role is to weave disparate parts into a cohesive whole.

Shackleton was the ultimate weaver. He was a “people-first” leader who stripped away Edwardian hierarchy to create a networked, horizontal team—abandoning the distance of a commander for the camaraderie of a peer. He possessed a “lively intellectual curiosity,” realising that in complexity, as Cleveland described, “everything is related to everything else.” Whether it was learning the nuances of navigation or understanding the psychological needs of the ship’s cook, Shackleton knew that the “chief integrator” must understand the diverse perspectives of every stakeholder to make something new happen.

Unwarranted optimism as a survival strategy

Perhaps the most striking overlap between these philosophies is the role of optimism. Cleveland insisted on “unwarranted optimism,” which is often associated with “stoic resilience.” The latter is not defined as a denial of reality, but as a strategic refusal to let pessimistic data paralyse collective action.

Perhaps the most striking overlap between these philosophies is the role of optimism. Cleveland insisted on “unwarranted optimism,” which is often associated with “stoic resilience.” The latter is not defined as a denial of reality, but as a strategic refusal to let pessimistic data paralyse collective action.

The Cleveland concept is broadly the conviction that a positive outcome is possible even when the “experts,” the situations, or the human elements suggest otherwise. Shackleton was indeed an “unwarranted optimist” who used the “balcony view” to synthesise this expertise while maintaining the “grit” to move forward.

Thus, Shackleton followed Heifetz’s rule: keep the tension high enough to motivate change, but low enough to prevent the organisation from “blowing up.” When the mission changed from “exploration” to “survival,” his optimism was not a delusion; it was what Cleveland called a “special responsibility for the future.”

Giving the work back

Heifetz warns leaders not to take the “work” off people’s shoulders. Shackleton did not just carry his men; he made them responsible for one another. He “gave the work back” by assigning tasks that maintained their dignity—training dogs, maintaining camp, and preparing for the daring 800-mile open-boat journey to South Georgia Island.

This is a classic example of “extreme adaptation,” where the leader must move from the “balcony” back to the “dance floor” to execute a high-risk, high-reward strategy for the survival of the entire system. Shackleton did exactly this when he launched the tiny lifeboat James Caird with his five companions for an audacious 800-mile, 16-day voyage across the world’s most treacherous seas—from uninhabited Elephant Island to South Georgia in 1916.

Enduring relentless winter storms and weathering three rescue missions from South Georgia and the Falklands, Shackleton refused to yield. It was only on his fourth attempt—aboard a borrowed Chilean tugboat—that he finally returned to the desolate shores of Elephant Island to bring all his men home alive.

In all this, Shackleton understood Cleveland’s concept of “self-agency” and the meaning of courage. He had no time for self-pity or paranoia, and he expected his crew to reach for their own “brass rings” of survival. In today’s “nobody-in-charge,” decentralised governing system, leadership is increasingly “self-selected” by those willing to be leaders and taking individual accountability for general outcomes.

Certainly, Shackleton’s success was not just his own; it was the result of 27 men each grabbing their own “brass ring” for collective survival. This reflects the gold standard for leadership in 2026: individual “self-selection” contributing to systemic resilience—a global necessity.

The self-selected leader

Possibly the most pressing lesson for the 21st century leadership is Cleveland’s concept of “self-selection.” In a horizontal, networked world, no one is coming to save us. Leadership is no longer a title granted by a king, a board, or a cabinet; it is a responsibility seized by those willing to reach for the “brass ring.”

Shackleton, known to his men simply as “the boss,” did not lead because of a commission from the king. He led because, when the ice closed in, he was the one willing to take personal responsibility for outcomes. He understood that “victim mindsets” are the luxuries of followers; authentic leaders only have time for action—never for complaints or retribution.

Leaders who spend time complaining about a situation are quickly bypassed by those who adapt to it. The pragmatic and wise Shackleton understood this as natural law: the ice is always shifting, as if Nature’s God were at work.

Leadership for the 2026 and beyond

As we navigate our own “Coldest War” of geopolitical shifts and technological disruption, the mandate for authentic leadership has changed. We can no longer rely on technical fixes for adaptive human problems; therefore, it is futile to solve complex cultural shifts with outdated hierarchies.

To lead today is to be a Shackletonian integrator: stay on the balcony to see the patterns, yet stay on the dance floor to lead by example. After all, as Cleveland reminded us, leadership is an attitude—not a skill; thus, it is better to recognise that taking risks is the only path to victory.

Today’s leaders face unfamiliar, “Antarctic” levels of natural and human complexity because hierarchies are fading, information is everywhere, and collaborative spirit is the force multiplier. To succeed in a “nobody-in-charge” world, you must still be “the boss” in the Shackletonian sense: like his crew did, people would follow those willing to take personal responsibility for general outcomes.

In the end, Shackleton did not cross Antarctica; instead, he did something much harder and more noble: he kept his humanity intact while the world around him cracked. Leadership is not about the ship you sail; it is about the people you mobilise when the ship sinks. In the coldest landscape of modern geopolitics, the most valuable resource is not the cold data on your screen: it is the optimism and moral courage in our souls.

(The author, a former US diplomat and NATO military professor, is the recipient of the Albert Nelson Marquis Lifetime Achievement Award from Marquis Who’s Who in America for his work as a global leader in higher education and international diplomacy. He also received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Sri Lanka Foundation in Los Angeles, California. An alumnus of the University of Sri Jayewardenepura’s Management Faculty, the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs, and the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, Dr. Mendis has served as a presidential advisor on national security education at the US Department of Defense—an appointment by the Biden White House. He has worked under six US presidents in both Democratic and Republican administrations in the Departments of Agriculture, Energy, Defense, State, and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in US Congress. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and they do not represent his affiliated institutions or governments)