Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday, 18 December 2025 04:44 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

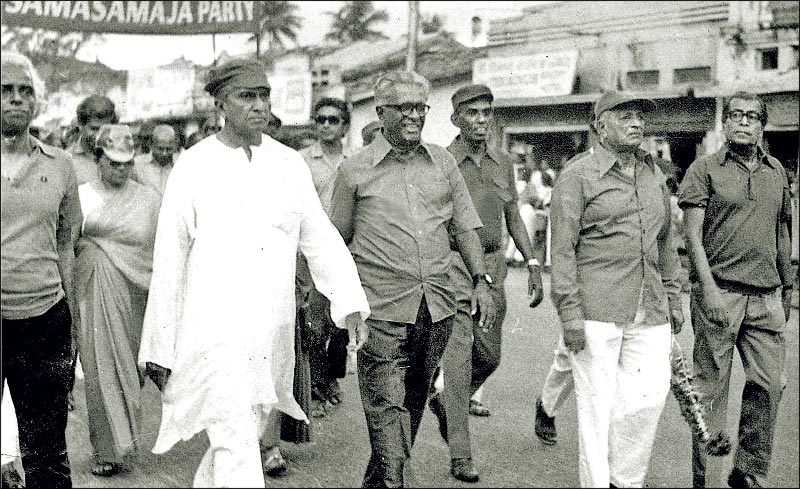

V. Karalasingham, P.O. Vimalanaga, Vivienne Goonewardena, Hector Abhayavardhana, Leslie Goonewardene, Colvin R de Silva, Osmund Jayaratne, N.S.E. Perera, N.M. Perera and Bernard Soysa participating in a LSSP rally – File photo

The Left may be weaker and fragmented; nevertheless, the relevance and need for a Left alternative persist. If the LSSP can celebrate its 90th anniversary as a reunited party, that could pave the way for a stronger and united Left as well. Merely discussing the history of the LSSP and the Left is insufficient; action is required

The Left may be weaker and fragmented; nevertheless, the relevance and need for a Left alternative persist. If the LSSP can celebrate its 90th anniversary as a reunited party, that could pave the way for a stronger and united Left as well. Merely discussing the history of the LSSP and the Left is insufficient; action is required

On the occasion of the ninetieth anniversary of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), this article highlights the party’s positions on constitutional matters. When the LSSP was founded, it had two primary objectives: obtaining complete political independence for Sri Lanka and building a socialist society. The first of these was achieved in two stages. The LSSP directly contributed to achieving semi-independence in 1948 through its anti-imperialist struggle and full political independence in 1972. The second objective remains a distant goal.

On the occasion of the ninetieth anniversary of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), this article highlights the party’s positions on constitutional matters. When the LSSP was founded, it had two primary objectives: obtaining complete political independence for Sri Lanka and building a socialist society. The first of these was achieved in two stages. The LSSP directly contributed to achieving semi-independence in 1948 through its anti-imperialist struggle and full political independence in 1972. The second objective remains a distant goal.

Citizenship Act

In the very second year after independence, the D. S. Senanayake Government acted to deny citizenship to the Hill-Country Tamil community and, consequently, deprived them of voting rights. In the 1947 election, many Hill-Country Tamils who voted as British subjects were inclined toward the Left, and especially toward the Sama Samaja Party. In that election, the Ceylon Indian Congress won seven seats, and with the support of plantation workers in areas where they were numerous, several left-wing candidates were also elected.

Seeing the long-term danger in this alliance, the Sri Lankan capitalist class ensured that the Citizenship Act defined the term “citizen” in a way that denied citizenship to hundreds of thousands of Hill-Country Tamil people. As a result, they also lost their voting rights. At that time, it was the Left, led by the Sama Samaja Party, that opposed this.

While the Tamil Congress, a coalition partner of the Government at the time, voted in favour of the legislation, S.J.V. Chelvanayakam stated that the inability of Tamil leaders to protect their cousins, the Hill-Country Tamil community, showed that being a partner in a Colombo-based Government brought no benefit to minority groups. He argued that the lesson to be learned was the need for self-government in the regions where they lived. Chelvanayakam’s founding of the Federal Party was one consequence of this process.

Although section 29 of the 1947 Constitution purported protection by providing that no law shall make persons of any community or religion liable to disabilities or restrictions to which persons of other communities or religions are not made liable, neither the Supreme Court of Ceylon nor the Privy Council in England, which was then the country’s highest appellate court, afforded any relief to the Hill-Country Tamil community.

When the LSSP was founded, it had two primary objectives: obtaining complete political independence for Sri Lanka and building a socialist society

When the LSSP was founded, it had two primary objectives: obtaining complete political independence for Sri Lanka and building a socialist society

Parity of status for Sinhala and Tamil and the ethnic issue

When the UNP and the SLFP, both of which had previously agreed to grant equal status to the Sinhala and Tamil languages, reversed their positions in 1955 and supported making Sinhala the sole official language, the LSSP stood firmly by its policy of parity. Earlier, when a group of Buddhist monks met N. M. Perera and told him they were prepared to make him Prime Minister if he agreed to make Sinhala the only official language, he rejected the proposal. Had the country heeded Colvin R. de Silva’s famous warning— “One language, two countries; two languages, one country”—the separatist war might have been averted. Because the Left refused to be opportunistic, it lost public support.

During the 1956 debate on the Official Language Bill, Panadura LSSP MP Leslie Goonewardene warned: “The possibility of communal riots is not the only danger I am referring to. There is the graver danger of the division of the country; we must remember that the Northern and Eastern provinces of Ceylon are inhabited principally by Tamil-speaking people, and if those people feel that a grave, irreparable injustice is done to them, there is a possibility of their deciding even to

break away from the rest of the country. In fact, there is already a section of political opinion among the Tamil-speaking people which is openly advocating the course of action.” It is an irony of history that Sinhala was designated the sole official language in 1956, yet in 1987, both languages were formally recognised as official.

Had the country heeded Colvin R. de Silva’s famous warning— “One language, two countries; two languages, one country”—the separatist war might have been averted. The failure of the 1972 Constitution to make both Sinhala and Tamil official languages was a defeat for the Left

Had the country heeded Colvin R. de Silva’s famous warning— “One language, two countries; two languages, one country”—the separatist war might have been averted. The failure of the 1972 Constitution to make both Sinhala and Tamil official languages was a defeat for the Left

1972 Republican Constitution

Colvin’s contribution to the making of the 1972 Republican Constitution, which severed Sri Lanka’s political ties with Britain, was immense. Preserving the parliamentary system, recognising fundamental rights, and incorporating directive principles of State policy that supported social justice were further achievements of that Constitution. It also had its weaknesses, and any effort to assign full responsibility for them to Colvin must also be addressed.

In the booklet that he wrote on the 1972 Constitution, he said the following regarding the place given to Buddhism: “I believe in a secular state. But you know, when Constitutions are made by Constituent Assemblies, they are not made by the Minister of Constitutional Affairs.” What he meant was that the final outcome reflected the balance of power within the Constituent Assembly. As a contributor to constitution drafting, this writer’s experience confirms that while drafters do have a role, the final outcome on controversial issues depends on the political forces involved and mirrors the resultant of those forces.

In fact, the original proposal made by Colvin and approved by the Constituent Assembly was that Buddhism should be given its “rightful place” as the religion of the majority. However, the subcommittee on religion, chaired by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, changed this to “foremost place.” It is believed that her view was influenced by the fact that one of her ancestors had signed the 1815 Kandyan Convention, in which Buddhism was declared inviolable, and the British undertook to maintain and protect its rites, ministers, and places of worship.

As Dr. Nihal Jayawickrama, a member of the committee that drafted the 1972 Constitution has written, the original draft prepared by Colvin did not describe Sri Lanka as a unitary State. However, Minister Felix Dias Bandaranaike proposed that the country be declared a “unitary tate”. Colvin’s view was that, while the proposed Constitution would have a unitary structure, unitary constitutions could vary substantially in form and, therefore, flexibility should be allowed. Nevertheless, the proposed phrase found its way to the final draft. “In the course of time, this impetuous, ill-considered, wholly unnecessary embellishment has reached the proportions of a battle cry of individuals and groups who seek to achieve a homogenous Sinhalese state on this island”, Dr Jayawickrama observed.

Indeed, the failure of the 1972 Constitution to make both Sinhala and Tamil official languages was a defeat for the Left. Allowing the use of Tamil in the courts of the Northern and Eastern Provinces and granting the right to obtain Tamil translations in any court in the country were only small achievements.

The National People’s Power, in its presidential election manifesto, promised a new Constitution that would abolish the Executive Presidency, devolve power to provinces, districts, and local authorities, and grant all communities a share in governance. However, there appears to be no preparation underway to fulfil these promises. It is the duty of the Left to press for their implementation

The National People’s Power, in its presidential election manifesto, promised a new Constitution that would abolish the Executive Presidency, devolve power to provinces, districts, and local authorities, and grant all communities a share in governance. However, there appears to be no preparation underway to fulfil these promises. It is the duty of the Left to press for their implementation

Devolution

The original Tamil demand was for constitutionally guaranteed representation in the legislature. Given that in the early stages, they showed greater willingness to share power at the centre than to pursue regional self-government, it is not surprising that the Left believed that ethnic harmony could be ensured through equality. After the conflict escalated, N. M. Perera, now convinced that regional autonomy was the answer to the conflict, wrote in a collection of essays published a few months before his death: “Unfortunately, by the time the pro-Sinhala leaders hobbled along, the young extremists had taken the lead in demanding a separate State. (…) What might have satisfied the Tamil community twenty years back cannot be adequate twenty years later. Other concessions along the lines of regional autonomy will have to be in the offing if healthy and harmonious relations are to be regained.”

After N. M.’s death, his followers continued to advance the proposal for regional self-government. At the All-Party Conference convened after the painful experiences of July 1983, Colvin declared that the ethnic question was “a problem of the Sri Lanka nation and State and not a problem of just this community or that community.” While reaffirming the LSSP’s position that Sri Lanka must remain a single country with a single State, he emphasised that with Tamils living in considerable numbers in a contiguous territory, the State as presently organised does not serve the purposes it should serve, especially in the field of equality of status in relation to the State, the nation and the Government. The Left supported the Thirteenth Amendment in principle. More than 200 leftists, including Vijaya Kumaratunga, paid the price with their lives for doing so, 25 of whom were Samasamajists. The All-Party Representatives Committee appointed by President Mahinda Rajapaksa and chaired by LSSP Minister Tissa Vitharana, proposed extensive devolution of power within an undivided country.

Abolishing the Executive Presidency

It is unsurprising that N. M. Perera, who possessed exceptional knowledge of parliamentary procedure worldwide and was one of the finest parliamentarians, was a staunch defender of the parliamentary system. In his collection of essays on the 1978 Constitution, N. M. noted that the parliamentary form of government had worked for thirty years in Sri Lanka with a degree of success that had surprised many Western observers. Today, that book has become a handbook for advocates of abolishing the executive presidency. The Left has consistently and unwaveringly supported the abolition of the executive presidential system, and the Lanka Sama Samaja Party has contributed significantly to this effort.

The National People’s Power, in its presidential election manifesto, promised a new Constitution that would abolish the executive presidency, devolve power to provinces, districts, and local authorities, and grant all communities a share in governance. However, there appears to be no preparation underway to fulfil these promises. It is the duty of the Left to press for their implementation.

In an article published in June this year, to commemorate N. M. Perera’s 120th birth anniversary, the writer wrote: “The Left may be weaker and fragmented; nevertheless, the relevance and need for a Left alternative persist. If the LSSP can celebrate its 90th anniversary as a reunited party, that could pave the way for a stronger and united Left as well. Such a development would be the best way to honour NM and other pioneering leaders of the Left.” It is encouraging that some discussion on this matter has now emerged. Merely discussing the history of the LSSP and the Left is insufficient; action is required. It is the duty of leftists to disprove Bernard Soysa’s sarcastic remark, “left activists are good at fighting for the crown that does not exist.”

(The author is a President’s Counsel and an Attorney-at-Law)