Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Monday, 2 February 2026 00:18 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

For more than a decade, Sri Lanka’s ambition to secure a reliable energy future has centred on Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRUs). The promise of LNG as a panacea for our persistent energy shortages has led to a string of announcements, proposals, and Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs).

For more than a decade, Sri Lanka’s ambition to secure a reliable energy future has centred on Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRUs). The promise of LNG as a panacea for our persistent energy shortages has led to a string of announcements, proposals, and Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs).

Despite repeated attempts and great expectations, no LNG project has reached operational status. As policymakers and investors contemplate the next steps, it is vital to examine the sobering history and financial risks involved. We must also face the contractual complexities, environmental hurdles, and global market realities that continue to challenge Sri Lanka’s LNG journey. This article aims to alert stakeholders to the pitfalls and mounting risks associated with LNG investment, urging a more prudent and transparent approach to our energy future.

Sri Lanka’s troubled LNG journey: A decade of false starts

Over the past ten years, Sri Lanka has made many unsuccessful attempts to secure a FSRU for LNG regasification. From Chinese and Korean proposals to Indian and American joint ventures, the record is replete with MOUs that never matured into viable projects. In 2016, the BOI approved a US$500 million LNG plant in Hambantota, only for progress to stall indefinitely. The same year, the SK E&S Company of Korea submitted an unsolicited FSRU proposal, triggering a ‘Swiss Challenge’ tender process. However, this failed to attract counterbidders due to high upfront costs and incomplete submissions.

Other ventures, such as Petronet’s ISO tank supply proposal and New Fortress Energy’s agreement for an LNG terminal have similarly faltered, undone by economic, logistical, and environmental realities.

Each failed attempt has left Sri Lanka with little more than announcements and dashed hopes. The absence of tangible progress reflects deeper issues that go beyond mere project execution and point to systemic weaknesses in planning, financing, and risk management.

The financial quagmire: Capital intensity and poor credit ratings

LNG infrastructure is among the most capital-intensive ventures in the energy sector. Projects require massive upfront investment, long-term operational commitments and robust financial guarantees. Globally, only a handful of the 50+ FSRU projects proposed each year reach fruition, with three to five successful launches on average – a testament to the high bar for financial viability.

Sri Lanka’s poor credit rating and lack of a credible financial security package are major obstacles. Reputable FSRU suppliers and financiers, such as Golar, Exmar, Execelerate, MOL, BW and Hoegh consistently decline to bid on Sri Lankan projects, citing unacceptable risks. Multilateral agencies are reluctant to finance fossil fuel projects due to climate concerns. Deemed high-risk for both debt and equity participation, Sri Lanka is unable to attract serious investors or lenders. The result: repeated project cancellations, cost overruns, and a cycle of failed announcements with no guarantee of future success.

Meanwhile, dual-fuel power generation plants (300 MW HFO/LNG Yugadanavi and 350 MW diesel/LNG Sobadhanavi in Kerawalapitiya), built with the expectation of “low-cost” LNG availability, are running on costlier HFO and diesel, further increasing electricity prices (tariffs).

Contractual and operational complexities: The hidden risks

FSRU projects and LNG contracts are notoriously complex, often containing “take-or-pay” clauses that impose heavy penalties on buyers who fail to meet contracted volumes. These contracts typically hedge LNG prices, but market volatility can leave buyers exposed to unfavourable price movements. India’s experience with RasGas in 2015, where a $1 billion penalty was imposed for breaking a long-term contract, underscores the dangers of such arrangements.

Early termination of vessel leases – usually fixed-term contracts exceeding 15 years – can result in unaffordable penalties and leave the country with liabilities on depreciated assets. The technical and commercial risks extend across the entire supply chain, from gas discovery to end-user operations, abandonment, and decommissioning. Sri Lanka lacks experience with LNG facilities. When compounded by poor tender management, ad hoc analysis, and a fondness for unsolicited offers, the country is placed at a distinct disadvantage in negotiating these high-stakes contracts.

Environmental and social hurdles: Safety, protests, and delays

Environmental approvals are a formidable barrier for LNG projects. High population density, land acquisition challenges, and the risk of leaks from oil and gas pipelines have triggered NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard ) protests and public opposition. Natural gas projects carry higher safety risks than oil, with the potential for fatalities and catastrophic damage in case of leaks or accidents.

The experience in Thailand, where pipeline rerouting led to soaring costs and delays, and ongoing protests over leaking oil lines in Colombo illustrate the difficulties of securing unconditional environmental clearances. These clearances can take decades, and interruptions during production can be disastrous for lenders and equity holders. Transparency in safety studies and public scrutiny are industry norms that Sri Lanka has yet to fully embrace, leaving the country exposed to environmental and reputational risks.

Global market realities: Volatility and competition

The global LNG market is marked by extreme price volatility. LNG prices have ranged from USD 12 to 70 per MMBTU. The spot market risks price spikes and supply shortages, while contract pricing carries strictly enforced take-or-pay obligations. The rush by Europeans to secure LNG infrastructure, spurred by the loss of Russian gas, has redirected supply chains, making Europe a preferred destination for FSRUs and LNG cargoes.

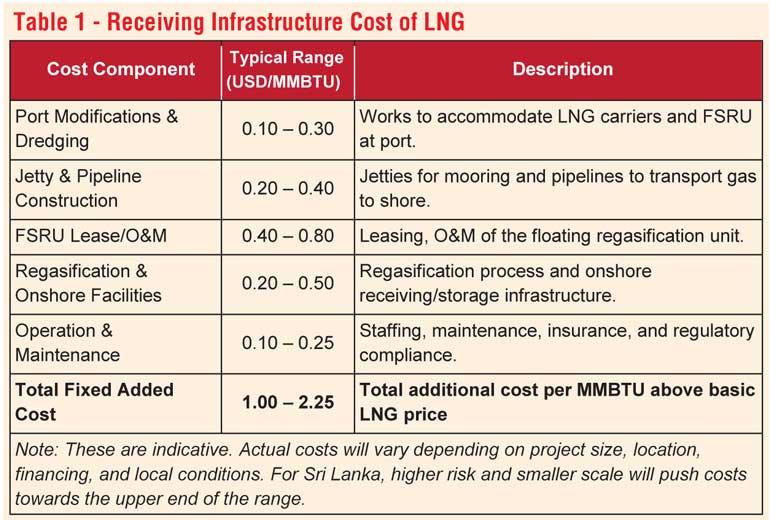

The quoted price excludes the infrastructure costs for receiving and delivering LNG. In addition to capital for FSRUs and terminals, LNG receiving facilities require significant fixed and ongoing expenses for port upgrades, jetties, pipelines, regasification, and gas handling. These fixed costs apply even when no LNG is received (see Table 1).

Once operational, recurring costs such as vessel leasing fees, maintenance, staffing, insurance, and stringent safety and environmental standards compliance add to the costs. These overheads can fluctuate based on international compliance norms and the need for technical upgrades, making long-term cost projections challenging.

Lessons from regional and global peers

Sri Lanka faces challenges like its neighbours. India’s Swan Energy FSRU took 16 years to launch; Bangladesh shifted from floating to onshore terminals for security and safety; Pakistan’s floating projects have met industry caution as global trends favour onshore solutions.

But onshoring near demand centres is infeasible in Sri Lanka.

These cases underscore the need for strong financial support, transparent procurement, independent reviews, and strict safety and environmental standards. Unlike others who succeed through careful planning and stakeholder involvement, Sri Lanka has relied on rushed, politically influenced decisions.

Policy implications and recommendations: Proceed with caution

Sri Lanka must reconsider its approach to LNG investment. Policymakers should recognise that LNG is not a magic bullet for our energy paralysis. Instead, Government and stakeholders should:

Conclusion: A call for prudent, transparent energy policy

It is incumbent upon policymakers, investors and the public to demand prudent, transparent, and evidence-based decision-making. The Energy Minister, Kumara Jayakody’s decision to step back from further LNG commitments deserves recognition as it demonstrates a willingness to prioritise caution and fiscal responsibility over short-term fixes.

However, history suggests that policy directions in Sri Lanka can shift with changing leadership or external pressures. It is essential, therefore, for all stakeholders to remain vigilant and ensure that evidence-based prudence continues to guide the nation’s energy future.

Given the risks and costs, Sri Lanka should look beyond LNG. Instead, the nation must prioritise its abundant renewable resources as part of a diversified and resilient energy strategy.

(The auhor brings over 50 years of experience in upstream oil and gas exploration, specialising in LNG contracting and infrastructure. He is skilled at aligning industry stakeholders to manage complex risks and has led major projects and negotiated multi-billion-dollar contracts, including floating systems. Nalin’s expertise includes project management, negotiations, and stakeholder relations. He received the Technical Excellence Award from Royal Dutch/Shell and has worked with major global energy firms. He trained as an engineer at University of Ceylon, Peradeniya later at University College London as a post graduate Government scholar. )