Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Tuesday, 10 February 2026 04:17 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

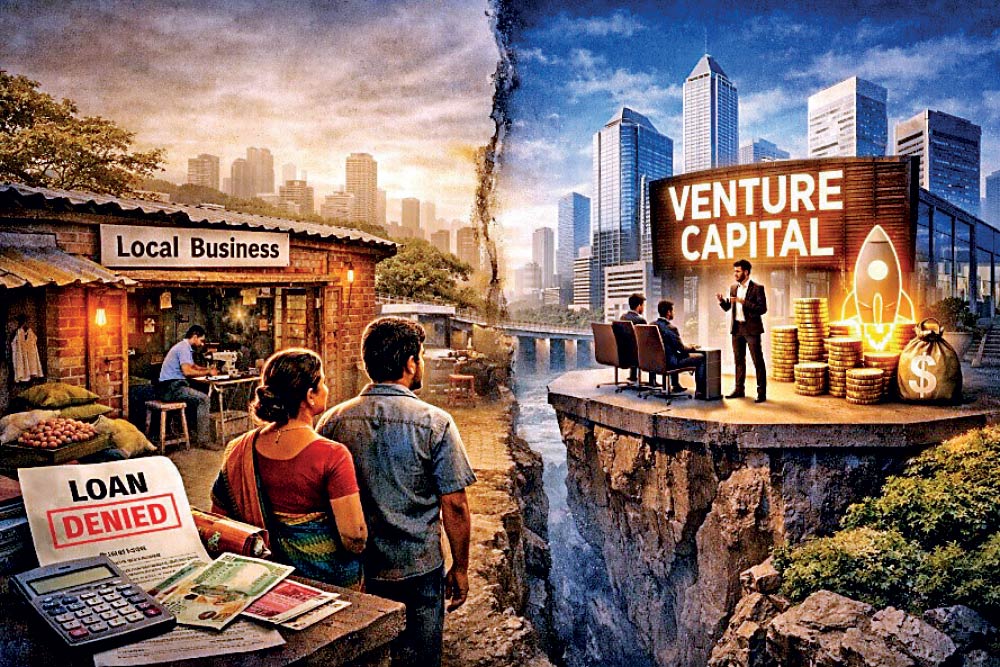

Venture capital is the fuel of innovation, disruption, and billions of success stories. From globally recognized market leaders to budding entrepreneurs, venture capitalists are the winners of the business world. But for most small and medium enterprises (SMEs), in countries like Sri Lanka, venture capital is more of a dream.

Venture capital is the fuel of innovation, disruption, and billions of success stories. From globally recognized market leaders to budding entrepreneurs, venture capitalists are the winners of the business world. But for most small and medium enterprises (SMEs), in countries like Sri Lanka, venture capital is more of a dream.

SMEs are widely identified as the backbone of the Sri Lankan economy. They account for the largest share of employment, contribute to the development of rural areas, and improve the living conditions of locals. Thus, when looking for growth capital, many of them get stuck in the middle ground since they are too large for Microfinance and too ordinary for venture capital.

Venture capital focuses on rapidly growing businesses with the ability to generate higher profits. Investors tend to invest in businesses that have the potential to scale quickly and dominate the market. Mostly, the technology-driven startups that are in urban areas like Colombo with access to investors and global markets capture the favor of this model.

Due to the Geographical concerns and favorability for tech startups, the SMEs operating in manufacturing, agriculture, or traditional services, mainly in rural areas, were left aside from the investors’ vision. This difference leaves entrepreneurs outside major cities with fewer opportunities.

Another major challenge for Sri Lankan SMEs is the growing challenges in accessing bank finance. High interest rates, strict regulations, and lengthy approval processes make bank loans hard to access. Many budding entrepreneurs are forced to stop innovations and expansion.

This gap in finances leads to major economic effects. While SMEs are the backbone of the Sri Lankan economy, this limited access to capital slows job creation and economic resilience. When the funding reaches a minority, innovation becomes concentrated, and inequity grows.

A more comprehensive financing ecosystem is a must to overcome this issue. Angel investors, impact funds, and SME focused venture capital can fill this gap, while policy measures such as government funds, credit guarantees, and tax incentives can boost investment in the underserved majority.

Venture capital itself must also evolve. Offering smaller investments, long-term expectations, and regionally focused investment plans could make venture capital more relevant to SMEs.

If venture capital remains favorable only to the elite, the hope of Entrepreneurship will remain incomplete. Sri Lanka’s economic future not only remains in a few high-profile startups, but also in empowering many SMEs that keep the nation’s economy running.

(The author is a fourth year Entrepreneurship Undergraduate at University of Sri Jayewardenepura)