Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 28 February 2024 00:22 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The pressure on the common man and the middle class is enormous and it keeps escalating in terms of the frequent price revisions on critical services followed by the prices of essential goods and services

The current engagement of IMF in Sri Lanka, is obviously a ‘desperate invitation’ of the Sri Lankan authorities, when all options were exhausted due to the absence of a strategy to leverage our reserves and resources in an effective manner, based on national priorities.

The current engagement of IMF in Sri Lanka, is obviously a ‘desperate invitation’ of the Sri Lankan authorities, when all options were exhausted due to the absence of a strategy to leverage our reserves and resources in an effective manner, based on national priorities.

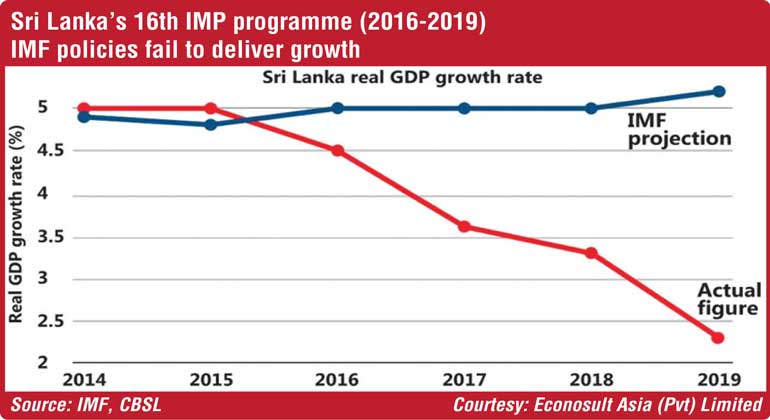

IMF conditions have historically been ‘prescriptive’ in nature, just like the paracetamol for pain, which has been the ‘universal approach to almost all kinds of ‘bail-out’ cases that they initiated. The program in 2016 for Sri Lanka had almost the same conditions. There were no external shocks such as the pandemic, Ukraine war, etc., and we had reserves to manage the recurring expenditure without drifting towards any major economic crisis. The annual change of GDP was 4.8% in 2015 and then drastically dropped to 2.3% in 2018 and disaster struck in 2019. It will be interesting for IMF to highlight the root causes behind the failures (the IMF program started in 2016) and probably to publish as a case study in National Economics.

IMF programs, while designed to address economic challenges, can have negative impacts on developing countries, in particular. The following are the common criticisms and concerns, which we have already experienced:

1. Austerity measures: IMF programs often prescribe austerity measures as a condition for financial assistance. The measures implemented in Sri Lankan context have included reducing public spending, cutting subsidies, and implementing tax increases. While intended to restore fiscal discipline, these austerity measures have led to social hardships, particularly affecting vulnerable populations and the middle class in particular. Also, it disturbs the recommendations of IMF on SSN (Social Safety Net) prescribed in No. 13, page 13 of Article 23/116. The absence of the activation of a WBB (Welfare Benefits Board) may also be a contributory factor.

2. Social impact: The focus on fiscal consolidation and economic reforms have largely neglected and/or compromised the social development priorities for Sri Lankans. The compelled reductions in public spending, especially on security, health and education, can have long-term negative effects on human development indicators in developing country like Sri Lanka.

3.Income inequality: The current IMF program has already contributed to widening income inequality further. There is a clear sign of the drifting of the middle class towards the poverty line. Affordability of the monthly wage earners has been diminished drastically and kept on falling. Austerity measures often impact lower-income groups more severely, exacerbating existing socio-economic disparities within a country. We are witnessing this on the rise of small to medium scale crimes, animosity of ‘have-nots’ towards the ‘haves’ and ongoing frauds and robberies.

4.Exchange rate policies: IMF programs may require countries to adopt specific exchange rate policies, such as allowing currency depreciation. The applicability of this measure is debatable in a country like Sri Lanka, which has been heavily dependent on imports for goods and services, and increased costs for imported goods, negatively affecting consumers and also has led to relatively higher inflation (almost triple in cost, in comparison to 2020). It argues that this may improve export competitiveness, however, the competitiveness of Sri Lanka in the global market is debatable, when the Nation has almost lost its ‘comparative’ and ‘competitive advantages’ by ‘resorting to low-level trading tactics for short term gains’.

5. Democratic accountability: Critics says that IMF programs undermine democratic accountability by imposing economic policies that may not align with the preferences of the local population. This is absolutely evident, when it comes to Sri Lanka and how IMF treats to powerful nations. It also obvious that the conditions attached to assistance can limit a country’s policy autonomy, which we witness so far and experienced. The government has no option, but succumb to every recommendation, in the absence of the bargaining power.

6. Financial stability risks: In some cases, the conditions set by the IMF may contribute to financial instability. For example, rapid and large-scale financial liberalisation, encouraged by IMF programs, can expose countries to risks associated with volatile capital flows. This brings numerous benefits, but known to create macroeconomic imbalances and increase financial vulnerabilities. However, sound empirical evidence has not been found to explain the impact in Sri Lanka.

7. Macroeconomic impact: Critics contend that the emphasis on short-term macroeconomic stabilisation may not be suitable for all countries. In some cases, policies recommended by the IMF may lead to a contraction in economic activity, hindering long-term development prospects. No doubt that the long-term development has abruptly been stopped with the implementation of IMF programs and lack of investment capital in Sri Lanka.

It’s important to note that while the IMF has been a key global player in addressing financial crises and supporting economic reforms, the effectiveness and impact of its programs can vary based on the specific circumstances of each country. Government has to address these concerns with careful consideration of the unique economic, social, and political context of the Sri Lanka, which is trapped in a self-made disaster.

The best-case example was Indian BOP crisis in 1986 and 1990s. India had a kind of National Strategic Plan, in reviving the economy with clearly identified priorities to overcome the crisis in 1986 and 1990s. We are yet to see such a plan. Instead, we are hearing the ‘heroic speeches in ‘Diyawanna’ and fairy tales by the members of the Government at press briefings.

Our economy suffered during 2020, 2021 and the unprecedented events in 2022, brought the economy to ‘ICU’,’ which did not have an adequate ‘life-support’ system due to the abuse and misuse of ‘economic resources’ by the successive Governments, as they were not reading the situation clearly, but kept on plastering the working capital gaps with large-scale borrowings. Case example: $ 12 billion ISBs – 2015 to 2019, as opposed to $ 5 billion of ISBs – 2009 to 2014.

The impact of the recommendations/conditionalities of IMF has resulted in the closures of many SMEs, migration of number of professionals largely due to the revision of personal income tax and diminishing income for recurring expenditure. The effects have also been able to vaporise the ‘disposable income’ of the people in thin air, particularly the ‘purchasing power’ of the middle-class. In short, the consumption is declining. The middle class and consumption are vital for any type of economic revival. Published news stated that more than 2,000 SMEs have been forced close after the first tariff revision and after recent one, surely, there are more to expect.

The Government nursing processes of the ‘sick economy’, should be given credit for restoring the political stability, which is fundamental for economic and social stability. The Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Monetary Board, Secretary to the Ministry of Finance should be applauded for the ‘nursing efforts so far’. In short, the President and Government has put ‘brakes on the free falling from 2022’, however, the falling does not seem to have halted and the falling still continues.

The larger issues like the rising energy cost, cost of living, trade mafia, trade union mafia and escalating crime rate are still affecting the stability of the economy. The pressure on the common man and the middle class is enormous and it keeps escalating in terms of the frequent price revisions on critical services followed by the prices of essential goods and services. Excessive indirect taxation is further distressing the business and consumption in every sector and witnessing the closures of numerous business entities. Everyone knows that the ‘taxation’ comes after the ‘consumption’ even in the English dictionary.

The immediate problem for the Government is the ‘large revenue gap’ and that cannot be addressed only by fondly adapted tax schemes, but reviving the traditional sources of revenue and activating a few new. Therefore, the focus should be to enhance the consumption by revitalising the middle class, increase the production by mitigating the negative effects of taxation and reviving the SME sector to achieve the growth.

(The writer is the GM/CEO of Lanka Financial Services Bureau Ltd. (LFSBL), has been in the corporate sector for 38 years, holds an MBA (Sri, J), Certified Risk Management professional (RIMS-CRMP), Certified Information Systems Auditor (CISA), Chartered Marketer, Researcher, writer and a senior lecturer. He could be reached at [email protected].)