Saturday Jan 24, 2026

Saturday Jan 24, 2026

Monday, 23 June 2025 02:56 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Real improvements in governance must be distinguished from theatre

Bruce Schneier, a leading thinker about technology, coined the term “security theatre” to describe the practice of implementing security measures that provide a feeling of improved security while doing little or nothing to achieve it. Anyone who has been through a mall entrance where security devices exist, people go through dutifully, and beeps are ignored routinely has participated in security theatre.

Bruce Schneier, a leading thinker about technology, coined the term “security theatre” to describe the practice of implementing security measures that provide a feeling of improved security while doing little or nothing to achieve it. Anyone who has been through a mall entrance where security devices exist, people go through dutifully, and beeps are ignored routinely has participated in security theatre.

What is meant by “governance theatre” is the common Sri Lankan practice of enacting Constitutional and legislative measures that provide a feeling of improved governance with little or no effect.

Exhibit 1: Right to Information

After decades of effort, the right to access information, (RTI) was added to the Constitution in 2015 as Article 14A. The RTI Commission was established by Act No. 12 of 2016. It’s not without its flaws, which were pointed out through numerous articles published while the drafting committee was doing its work, but it was progress.

The RTI legislation has broad applicability, governing the information retention and disclosure practices not only of all Government departments, statutory bodies and companies where the Government holds a majority, but also private entities that receive Government and foreign funds. With broad applicability across the economy comes the requirement of a competent and well-resourced RTI Commission. The right to information cannot be assured without a regulator with teeth. Without such a regulator, information will not be disclosed and the culture of openness in government established. It is an essential government function that cannot be outsourced.

Though it has the authority to compel the disclosure of information by any Ministry and the right to access information is in the Constitution, the RTI Commission is not positioned as a supra-ministerial body like the National Audit Office. Instead, it has been positioned as an entity under the Ministry responsible for Mass Media, creating an instant conflict of interest. The parent Ministry which has to formulate the Commission’s budget requests has no interest in a fully resourced and empowered RTI Commission. Neither does the Ministry of Finance which approves its budget requests.

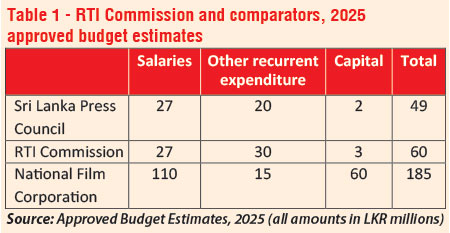

Therefore, it is no surprise that the RTI Commission is starved of funds, cannot attract or hold good professionals, and many are frustrated by its performance. It is given the same amount for salaries as the redundant Sri Lanka Press Council, which is under the same ministry, and only 11 million rupees more in total. A corporation that should be self-financing, the National Film Corporation, is given three times the funds of the RTI Commission.

The RTI Commission requires competent staff, including lawyers who do not come cheap, especially after the pay increases won by the Attorney General’s Department in 2015-19. The puny allocation for compensating the RTI Commission’s staff translates into inability to fill the cadre and to recruit and retain competent professionals. The comparator entities do not require professional staff of the level the RTI Commission does but are provided the same or more. Strangely, the Sri Lanka Press Council has a cadre of 10 while the RTI Commission has 19. If the cadre is filled, the average per employee would be less in the RTI Commission than in the Press Council.

Exhibit 2: Data protection

Exhibit 2: Data protection

The Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) is of general applicability. Depending on the success of digitisation efforts, pretty much every organisation in the country may soon fall within the scope of data protection regulation. The substantive provisions of Act No. 9 of 2022 are yet to be brought into effect, though the chapters enabling the creation of the Data Protection Authority have been in effect for more than a year.

Data protection is regulation. It requires compelling public and private organisations to act in ways that impose costs to themselves. It is a core function of government that cannot be outsourced. Implementing data protection takes money. Even in Europe, whose General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) served as the model for the Sri Lankan legislation, data protection authorities are under-resourced, do not have enough staff with the necessary technical skills, and take inordinately long to respond to complaints. It was reported by The New York Times in 2020 that all but three (Germany, Italy, and the UK) had annual budgets of less than Euro 25 million. The above benchmark may be interpreted to mean that a minimum of Euro 25 million (or Rs. 8.6 billion) a year is required to run an effective data protection authority capable of implementing this kind of complex law.

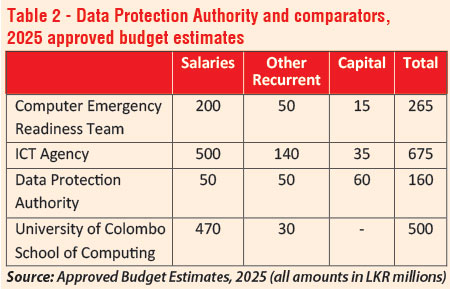

The first three rows show the allocations to the three entities under the Ministry of Digital Economy. The fourth row has been included to how much the government spends on one school of computing compared to agencies essential for the success of digitalisation. The DPA is truly the runt of the litter.

The DPA has been allocated less than 2% of the European benchmark. It is a mere fraction of the Rs. 2.2 billion administration and establishment expenditures reported for 2023 by the Telecom Regulatory Commission. More than a year after establishment, it has not had permanent director general (there have been two acting DGs) and there appears to be significant churn in the board as well. Is this a cause of the abysmal funding or an effect?

Beware of theatre

Beware of theatre

There is little debate about the need for better governance if Sri Lanka is to become a good place to live. The 2022 economic crisis and its continuing effects may be seen as a crisis of governance. But real improvements in governance must be distinguished from theatre. Otherwise, we will exacerbate the crisis, not remove the root causes.

Too often, civil society activists focus on making law, paying little heed to what happens after enactment. The private-sector lobbyists who pushed for cloning the GDPR were also focused on the law which they thought would get them European business. Now they are left with an unimplementable law and zero chance of getting the European adequacy certification.

They are not alone in this illusion. Organisations such as the Center for Law and Democracy that position Sri Lanka among the top-ranked in RTI have been taken in by the theatrical illusion and through their uncritical focus on black-letter law and neglect of what actually happens on the ground reinforce the illusion. But then, it is a mystery why anyone would take seriously a ranking that places Afghanistan as the world’s number one.

The best law is not one that is optimal in a technical sense, but one which is most appropriate for the local conditions. Otherwise it is governance theatre. Illusion may create warm feelings but does not change the world.