Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Wednesday, 24 September 2025 00:26 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

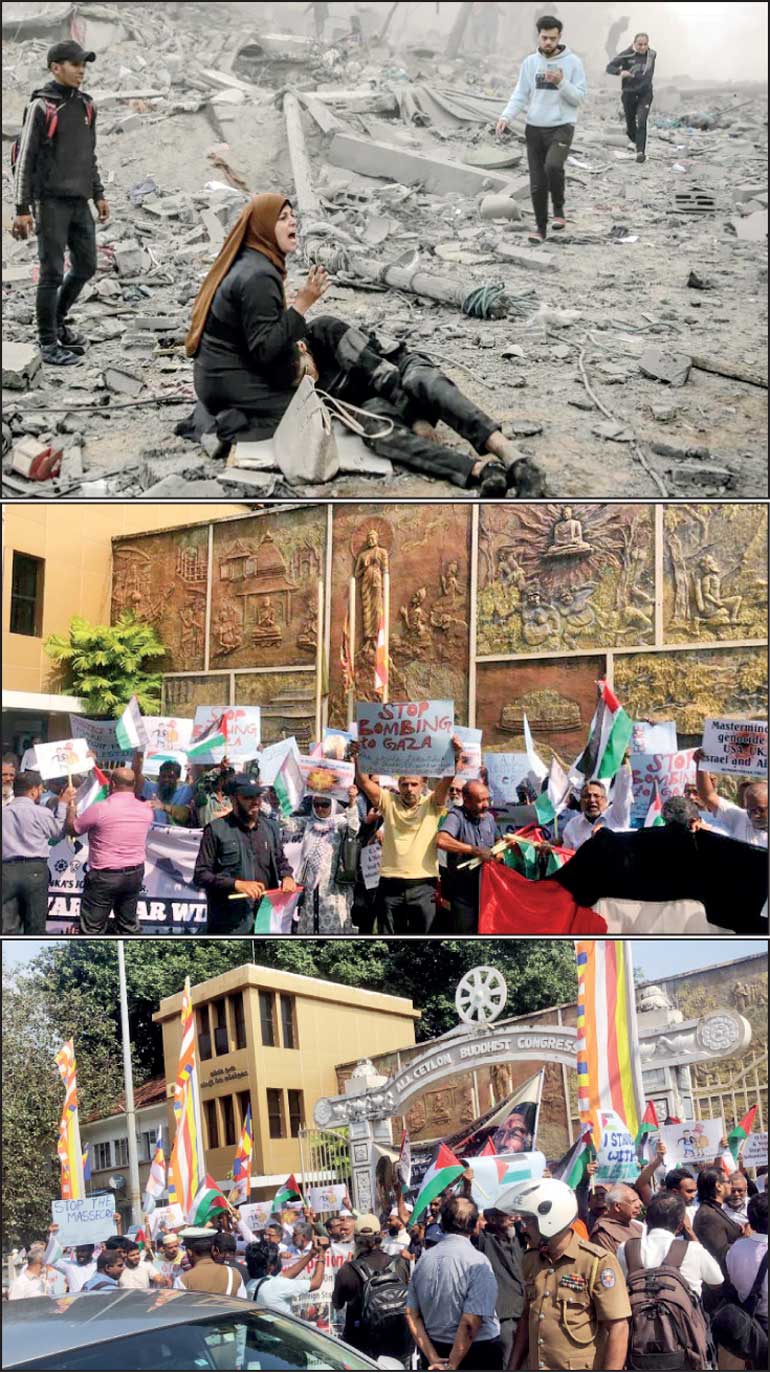

The finding by the United Nations that genocide is occurring in Gaza is an inflection point

The Government should support civil society and free media at home. Journalists should not be threatened for reporting on Gaza

Last week, the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, chaired by former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay, concluded that Israel has committed genocide in Gaza.

Last week, the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, chaired by former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay, concluded that Israel has committed genocide in Gaza.

The Commission of Inquiry found that four out of the five acts defined under the 1948 Genocide Convention are being carried out. They are: killing, causing serious bodily or mental harm, deliberately inflicting conditions of life calculated to bring about the destruction of the Palestinians in whole or in part, and imposing measures intended to prevent births.

This is not only a moral label on the constant scenes of devastation and horror merging from the Gaza Strip. It is not just a minor legal observation. It is a grave conclusion with far-reaching consequences for international law and for the global community. For Sri Lanka, which has long affirmed support for Palestine, the moment raises many questions. Can we speak more forcefully? What prevents us? And how might our own history figure into our current posture?

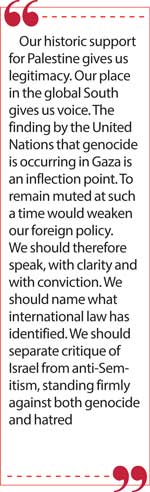

For decades Sri Lanka has voted in favour of Palestinian rights in the United Nations, called for ceasefires, demanded humanitarian access, and affirmed the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination. This has been consistent and visible. Yet today, when international institutions and many states speak with unprecedented clarity about genocide, Sri Lanka remains reticent. Other countries, from South Africa to Ireland, have issued strong condemnations. Over the weekend, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and Portugal took the monumental step of recognising the State of Palestine. At the time of writing, France and a slew of other European states are expected to follow suit, at the UN General Assembly in New York.

Why, then, does Sri Lanka hesitate to match this clarity?

Pre-emptive counterpoints

A recent article published in the Sri Lanka Guardian argued that anti-Semitism is on the rise in Sri Lanka. It suggested that anti-Semitic, anti-Jewish and anti-Israeli sentiments function as a single ideology, and that this supposed trend in Sri Lanka “should be interpreted as an ideological endorsement of global Islamic extremism”.

Such articles and efforts to legitimise critiques of Israel’s policy are not uncommon. From a certain perspective, one may even find them bold in attempting to defend an increasingly morally untenable position. From a more analytical lens, however, one could see such efforts as instruments of soft power. They shape perceptions, frame narratives, and create hesitancy in how issues are later discussed in public. It is against this backdrop that warnings of anti-Semitism were raised, even as criticism of Israeli actions intensified globally.

The conflation of criticism of Israel with anti-Semitism is a central problem. Anti-Semitism is real, corrosive, and unacceptable. Yet equating opposition to the policies of the State of Israel with hatred of Jewish people is analytically flawed and politically counterproductive. It delegitimises genuine critique and shields a state from accountability under international law.

The conflation of criticism of Israel with anti-Semitism is a central problem. Anti-Semitism is real, corrosive, and unacceptable. Yet equating opposition to the policies of the State of Israel with hatred of Jewish people is analytically flawed and politically counterproductive. It delegitimises genuine critique and shields a state from accountability under international law.

Sri Lanka must be able to draw this distinction clearly. Otherwise, accusations of anti-Semitism will be used to silence debate, as has increasingly happened in Western societies. That cannot be allowed to limit our own discussions.

The obstacles to speaking out

Sri Lanka’s hesitation stems from several factors.

The first is the fear of reciprocal scrutiny. Many in policymaking circles believe that to speak too bluntly about genocide in Gaza invites renewed focus on allegations from Sri Lanka’s own conflict. Allegations of genocide and war crimes during the final stages of the conflict are still debated internationally. Navi Pillay herself was on panels that examined Sri Lanka’s post conflict period, and while those reports were highly critical of the country’s human rights record, they did not describe what occurred as genocide. For Sri Lanka, this difference should provide confidence rather than hesitation. While contexts may differ, if the same authority did not apply the label to us, then invoking it now in relation to Gaza does not automatically invite the same charge against Sri Lanka.

The second obstacle is diplomatic and economic. Despite its official pro-Palestine stance, Sri Lanka maintains robust ties with Israel. Workers are sent there for employment, trade relations exist, and diplomatic contacts continue. Officials argue that to condemn Israel too strongly risks economic cost. Yet moral positions cannot always be traded for short term benefits. If Sri Lanka is to uphold principles of international justice, particularly in wake of the systemic shift that the State wants to live up to, it cannot remain paralysed by fear of economic retaliation.

The third obstacle lies in domestic politics and media framing. Officials often emphasise balanced diplomacy, urging caution in language that might inflame communal tensions. Segments of our society may wonder if there is an overt hypocrisy in condemning Israel, while being reticent about exploring domestic accountability. Others still may preach insularism, and ask why the Government wishes to immerse itself in ‘someone else’s rubbish’. Such practices cultivate self-censorship and reinforce the perception that certain subjects are taboo. If we are to strengthen our democracy, such hesitation must be avoided, as it weakens society’s moral voice and leaves foreign policy captive to fear.

The fourth obstacle is the inertia of diplomatic culture. Even when international bodies make strong findings, the Sri Lankan bureaucracy often prefers vague language. They cite respect for procedure, the desire to avoid isolating allies, or the risk of disrupting bilateral relations. In practice this means Sri Lanka issues general calls for peace while avoiding the precise legal terms that give those calls weight.

Why hesitation is dangerous

The consequences of silence or softening of position are significant.

If genocide is identified by the UN and states continue to remain neutral, perpetrators are emboldened. They act with less fear of consequence. International law loses its meaning and normative power if findings are ignored.

Sri Lanka also risks losing diplomatic credibility. For decades, our support of Palestine has been consistent. To retreat at the very moment when the world is waking up to the severity of events in Gaza makes that history look hollow. We would be perceived as unable or unwilling to act on principles we have long proclaimed.

Sri Lanka also risks losing diplomatic credibility. For decades, our support of Palestine has been consistent. To retreat at the very moment when the world is waking up to the severity of events in Gaza makes that history look hollow. We would be perceived as unable or unwilling to act on principles we have long proclaimed.

Silence also deprives Sri Lanka of the chance to redefine its own legacy. The concern that speaking about Gaza might invite comparisons to Sri Lanka’s past should be inverted. By speaking clearly about the present, we demonstrate that we value accountability and justice in all contexts. Our own history does not need to be erased or excused. It can be acknowledged honestly, while still affirming that what is unfolding in Gaza is of a magnitude that meets legal thresholds that were not applied to Sri Lanka, and deserves to be called by its name.

A course for Sri Lanka

The way forward lies in combining clarity with responsibility. With the UN General Assembly well underway, there is potential for both the President and Foreign Minister to articulate a stronger policy position for Sri Lanka.

First, Sri Lanka should adopt precise language when referring to Gaza. If the UN Commission has found genocide, we should cite that finding directly. To do so is not to make a new allegation ourselves but to stand with established international law.

Second, Sri Lanka should distinguish between criticism of a state and hatred of a people. This line must be drawn explicitly. Condemn anti-Semitism wherever it appears, but make equally clear that criticism of Israel’s government is not the same thing. This protects the integrity of our position and denies those who seek to discredit it the easy accusation of bias. Our statements could reflect international law, avoiding ethnic or religious framing, so that critique cannot be misrepresented as prejudice or a capitulation to terrorism.

Third, Sri Lanka should ground its statements in legal authority. The Genocide Convention, International Court of Justice proceedings, and UN Human Rights Council debates are available tools. This ensures that our voice is not rhetorical but principled, and able to carry weight. Acknowledging global injustices does not erase the need for our own self-reflection, but it shows a willingness to apply principles universally.

Fourth, we should use multilateral forums to press our case. Whether in the UN, the G77, the Non-Aligned Movement, or in cooperation with states that have already spoken strongly, Sri Lanka can reinforce global momentum. This would also support in preserving our relations with states, rather through unilateral confrontation.

Fifth, the Government should support civil society and free media at home. Journalists should not be threatened for reporting on Gaza. Youth should not be intimidated for protesting. Exchanges and visits organised by foreign governments should be transparent and subject to scrutiny. Only then will debate remain free and credible.

Finally, Sri Lanka should ensure policy consistency. Public statements must be matched by tangible actions. This could include humanitarian assistance for Palestinians, diplomatic support in international fora, and careful evaluation of how labour or economic relations with Israel are structured.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka has the capacity to speak with clarity. Our historic support for Palestine gives us legitimacy. Our place in the global South gives us voice. The finding by the United Nations that genocide is occurring in Gaza is an inflection point. To remain muted at such a time would weaken our foreign policy.

We should therefore speak, with clarity and with conviction. We should name what international law has identified. We should separate critique of Israel from anti-Semitism, standing firmly against both genocide and hatred. Sri Lanka must seize this moment not to retreat in fear of our own history but to reaffirm our belief that principles matter, whether in Gaza or in Sri Lanka.

By doing so we not only affirm solidarity with Palestinians but also reaffirm Sri Lanka’s own moral standing in the world.

(The author is a political analyst, and lecturer in international relations, political economy and democracy and democratisation.)