Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Tuesday, 26 August 2025 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

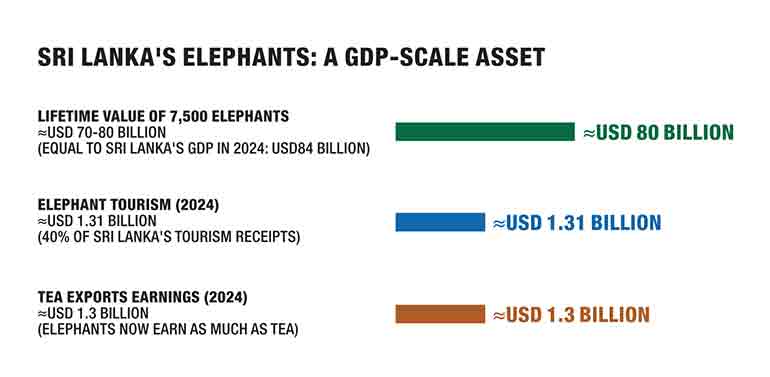

Elephants have become a GDP-scale economic asset

In November 2020, we argued in this paper that “a cut tree, a dead elephant, is a lost tourism dollar in the future.” At the time, we estimated the lifetime value of a wild elephant at $ 11 million and warned that deforestation, human-elephant conflict, and short-sighted planning were dismantling the very assets Sri Lanka most needed to attract high-value travellers.

Five years later, the future has arrived and with startling clarity. Elephants are no longer a peripheral tourism attraction. They are the central economic engine of Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange earnings.

From pre-crisis to recovery: Tourism’s remarkable turnaround

If the past decade has taught Sri Lanka one lesson, it is that tourism is the fastest way out of crisis.

If the past decade has taught Sri Lanka one lesson, it is that tourism is the fastest way out of crisis.

In 2018, the industry generated $ 5.6 billion from 2.5 million visitors, briefly standing as the nation’s top foreign exchange earner. The 2019 Easter Sunday attacks cut earnings to $ 3.6 billion, and by 2022, the economic collapse had almost paralysed the sector.

Yet tourism rebounded with extraordinary speed. In 2024, arrivals climbed to 2.05 million and receipts to $ 3.17 billion, outpacing remittances, exports, and FDI in growth. In the first eight months alone, tourism brought in $ 2.2 billion, a 66% year-on-year increase.

This resilience underscores a critical truth: while exports, remittances, and FDI require years of structural reform, tourism has proven it can rebound quickly and inject immediate foreign exchange. And at the centre of this turnaround lies Sri Lanka’s greatest comparative advantage – its elephants.

Elephants: The strongest foreign exchange engine

In 2024, 851,365 foreign visitors (nearly 41% of arrivals) came specifically to see elephants-focused national parks and forests. They generated $ 1.31 billion, or 40% of total tourism receipts.

That makes elephants alone as valuable as Sri Lanka’s tea exports, long considered the backbone of the economy. Put differently, 7,500 wild elephants are now generating the same foreign exchange as an entire tea plantation industry.

This shift is profound: elephants have become a GDP-scale economic asset.

Export vulnerability: When the Rose Garden sneezes, Colombo catches a cold

By contrast, Sri Lanka’s merchandise export model is fragile.

In 2024, goods exports totalled $ 12.77 billion, with the garment sector contributing $ 4.8 billion. But nearly 40% of garment exports go to the US, leaving the industry hostage to American trade policy.

In April 2025, the White House announced sweeping tariffs from the Rose Garden, initially at 44% and subsequently revised to 20%. Even at this lower rate, the damage was clear: a single announcement put 300,000 jobs and $ 2 billion in forex earnings at risk.

This is the peril of dependence. Our export strategy is overly reliant on a single market and vulnerable to political decisions beyond our control.

The limits of remittances and FDI: Labour flows outward, capital slows inward

For decades, remittances underpinned Sri Lanka’s external account. In 2024, inflows rose 10% to $ 6.57 billion. Yet the composition is troubling: most comes from unskilled labour in the Middle East, which caps per-worker earning power.

In contrast, India and the Philippines export skilled professionals in IT, healthcare, and engineering — earning three to four times more per worker. Without a shift toward skills-based migration, Sri Lanka has become locked into low-value remittance markets that deliver volume but little resilience.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has been even weaker. Between 2015 and 2019, inflows averaged just $ 1.2 billion annually, growing at less than 1% per year. Post-crisis, inflows improved slightly, recording a 2020–2023 CAGR of ~13%. But even this recovery pales in comparison to regional peers. Structural bottlenecks – which includes policy uncertainty, infrastructure gaps, and failure to integrate into global supply chains — continue to deter large-scale investment. While Vietnam has become a hub for electronics and Thailand for automobiles, Sri Lanka remains on the sidelines, awaiting a breakthrough that never comes.

Both remittances and FDI bring foreign exchange, but neither delivers resilience or rapid scale. Unlike tourism, which proves it can rebound quickly and expand fast, these flows remain slow-moving and structurally constrained.

Contrast: The elephant advantage

Elephants, by contrast, are immune to tariffs, sanctions, or supply chain shocks. Their value is intrinsic, rooted in our ecosystems yet demanded globally.

In 2024, elephant-focused tourism earned $ 1.31 billion, nearly as much as tea, and a third of apparel exports. Unlike garments, where Sri Lanka competes against Vietnam and Bangladesh on cost, no other country can replicate Minneriya’s Gathering or Udawalawe’s wild herds.

Elephants are not just an advantage. They are Sri Lanka’s right to win in the global tourism economy.

Elephants as GDP-scale capital

The numbers are staggering:

Every elephant lost to human-elephant conflict or poaching erases $ 10.5 million from the country’s future forex balance sheet.

What makes this even more striking is efficiency. Tea plantations require hundreds of thousands of workers and vast amounts of capital employed. Elephants generate equal forex simply by existing in their natural habitats.

Jobs and rural prosperity

The employment footprint is equally transformative. In 2024, elephant-related tourism sustained nearly 200,000 jobs across hotels, safari jeeps, guides, restaurants, handicrafts, and cultural suppliers.

Each elephant tourist supports five to six rural jobs. For villages with few economic alternatives, elephants are not a nuisance. They are the single largest rural employer.

Protecting elephants, therefore, is the most effective means to rural development and poverty alleviation.

Policy imperatives for 2025

Sri Lanka’s elephants must be managed as a national economic asset. Four policy imperatives stand out:

Conclusion: From warning to wake-up call

In 2020, we warned in this paper that Sri Lanka had “never missed an opportunity to miss an opportunity.” Five years later, the evidence is overwhelming:

Our elephants are worth $ 80 billion. They sustain 200,000 livelihoods. They generate as much forex as tea without the capital and labour burden.

A dead elephant is a tragedy of nature. It is the destruction of a $ 10.5 million national asset and a direct blow to Sri Lanka’s future.

Protecting elephants is a matter of economic survival, national security, and our most unassailable right to win.

(The writers are business and brand strategists.)