Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Friday, 12 December 2025 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

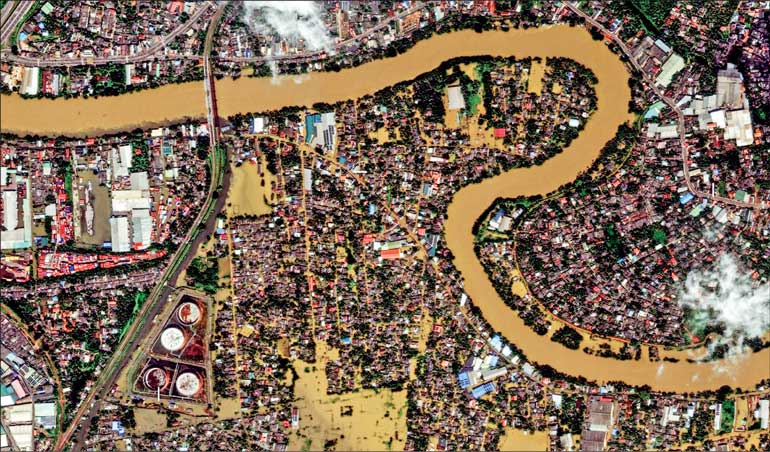

An aerial view of the flooding following the Ditwah cyclone - Pic courtesy UNDP, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s 2025 floods, intensified by Cyclone Ditwah, have forced the country into one of the most consequential fiscal conversations of the decade: how to finance resilience at a scale that matches the growing magnitude of climate loss. This is no longer an environmental debate. It is an economic one. The scale of the damage and the cost of rebuilding now position Sri Lanka among the clearest examples of why developing economies cannot adapt to climate extremes without massive, predictable and long-tenor climate finance.

Sri Lanka’s 2025 floods, intensified by Cyclone Ditwah, have forced the country into one of the most consequential fiscal conversations of the decade: how to finance resilience at a scale that matches the growing magnitude of climate loss. This is no longer an environmental debate. It is an economic one. The scale of the damage and the cost of rebuilding now position Sri Lanka among the clearest examples of why developing economies cannot adapt to climate extremes without massive, predictable and long-tenor climate finance.

The facts speak clearly. UNDP’s 2025 geospatial impact analysis shows that extensive flooding inundated large sections of the Colombo, Gampaha metropolitan corridor, where a significant share of national economic output is generated. According to the Disaster Management Centre’s official situation reports, thousands of homes, public buildings, roads, and critical infrastructure assets were damaged or destroyed, with service disruptions cascading through every sector of the urban economy (DMC 2025). WHO SEARO’s emergency update places the number of affected individuals at more than 5.2 million nationwide, making this one of the largest disaster impacts recorded in recent decades.

The economic translation of this devastation is stark. In preliminary submissions to development partners, the Government of Sri Lanka estimates that reconstruction and recovery will cost between $ 6–7 billion

equal to approximately 3%–5 % of GDP (Government of Sri Lanka 2025). These are not long-term estimates; these figures reflect the immediate needs required to restore urban functionality, housing, and economic connectivity. Adding indirect losses, as evidenced by internal modelling used by the World Bank, the total macroeconomic impact is likely significantly higher. Indirect losses such as disrupted supply chains, reduced industrial output, loss of labour hours, damage to SMEs, and the long-term corrosion of urban productivity often exceed direct destruction by two to three times in densely populated economies (World Bank 2025).

But Sri Lanka is not alone in its exposure. Across the world, climate-related disasters have triggered increasingly large demands for reconstruction, pushing international climate finance flows to surge. According to the most recent estimates by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), global public and private climate-related finance recently has been approaching

$ 600–700 billion per year, though the bulk goes toward mitigation (renewable energy, energy efficiency) rather than adaptation or resilience projects (OECD 2024). At the same time, multilateral institutions including the Green Climate Fund (GCF) the world’s largest dedicated climate adaptation fund have mobilised capital commitments of only tens of billions of dollars, even as requests from vulnerable countries multiply (GCF 2025 Annual Report).

$ 600–700 billion per year, though the bulk goes toward mitigation (renewable energy, energy efficiency) rather than adaptation or resilience projects (OECD 2024). At the same time, multilateral institutions including the Green Climate Fund (GCF) the world’s largest dedicated climate adaptation fund have mobilised capital commitments of only tens of billions of dollars, even as requests from vulnerable countries multiply (GCF 2025 Annual Report).

Sri Lanka, like many climate-exposed emerging economies, faces the most punishing version of the global climate paradox: it is losing the capital it already has while lacking the capital required to rebuild for the world it is entering. Conventional financing models, designed for stable climates and linear development, are fundamentally mismatched to adaptation needs that must operate at speed and scale. The 2025 floods did not create this misalignment, but they made it visible in a way impossible to ignore.

For Sri Lanka, this global financial backdrop presents a clear opportunity and a stark imperative. The $6–7 billion reconstruction need is small relative to the current global climate-finance flows. Yet without deliberate, structured access to those flows, Sri Lanka will struggle to rebuild not just infrastructure but resilience. Conventional financing models, designed for stable climates and linear development, are fundamentally mismatched to adaptation needs that must operate at speed and scale. The 2025 floods did not create this misalignment, but they made it visible in a way impossible to ignore.

The magnitude of the stranded and degraded asset base provides one of the strongest cases for climate finance in today’s global discourse. When urban transport networks, drainage systems, power infrastructure and commercial districts can lose functionality in a single event, they no longer behave like traditional assets. They behave like climate-sensitive liabilities that require systemic upgrading. Without climate finance, rebuilding will be piecemeal, reactive, and fiscally destabilising. With climate finance, those same assets can be re-engineered into resilient, long-life economic enablers, capable of sustaining productivity in a future of more frequent extremes.

The case for climate finance is therefore not framed in charity. It is an investment proposition with long-term returns. Every dollar invested in climate-resilient infrastructure yields between four to seven dollars in avoided losses and sustained economic output, according to the global evidence cited by development banks. For Sri Lanka, where urban economic density is high and vulnerability sharply rising, the multiplier effect is likely even greater. Rebuilding with resilience today helps prevent the next $6–7 billion loss event. Failure to do so ensures it.

What Sri Lanka needs is not sporadic project-based funding but a comprehensive climate-finance platform with multi-year predictability. This includes concessional long-tenor financing for resilient infrastructure, adaptation-focused development policy loans, resilience bonds, climate-risk pooling instruments, and structured blended finance for private-sector participation. Access to global climate funds must be accelerated through simplified pipelines and partnerships with accredited entities capable of rapidly deploying capital. When one flood can generate losses equal to several years of public capital investment, adaptation finance must become the backbone of development finance not an optional supplement to it.

The flooding also highlighted the unbearable fiscal asymmetry that climate-vulnerable countries face: they are asked to both service legacy debt and simultaneously fund climate adaptation, even as climate change erodes the asset base that generates tax revenue. Without new forms of climate finance, the fiscal stress becomes self- reinforcing: a Government repairs damage with scarce resources, another disaster strikes, debt rises, investment falls, and resilience becomes perpetually underfunded. Climate finance offers the only pathway to break this cycle by front-loading capital for resilience while sustaining fiscal space for development.

reinforcing: a Government repairs damage with scarce resources, another disaster strikes, debt rises, investment falls, and resilience becomes perpetually underfunded. Climate finance offers the only pathway to break this cycle by front-loading capital for resilience while sustaining fiscal space for development.

Sri Lanka’s experience is a microcosm of a global structural problem. Climate-vulnerable economies contribute the least to global emissions yet face the highest capital losses and must now compete for adaptation funding under frameworks designed for a different era. The 2025 floods offer a powerful demonstration of why climate finance must be scaled, simplified, and delivered at speed. The alternative is an accelerating divergence, where countries repeatedly rebuild infrastructure that cannot withstand the future, draining the very capital they need to grow. The economic case is therefore compelling and clear: climate finance invested in Sri Lanka today is not merely a humanitarian response but a safeguard of national productivity, fiscal stability, and future growth. It prevents stranded assets, increases resilience, supports private investment confidence and preserves the infrastructure on which modern economic life depends. The floods have revealed the true cost of under-funded adaptation and have illustrated with painful clarity why Sri Lanka cannot afford to rebuild alone.

If global climate finance is to have meaning, it must show up where the evidence is loudest. And today, few cases speak more clearly than post-flood Sri Lanka. Climate finance is no longer an environmental instrument; it is a macroeconomic necessity. The country’s road to recovery and its resilience in the decades ahead will depend on whether the world recognises this and  responds at a scale proportionate to the losses now in plain view.

responds at a scale proportionate to the losses now in plain view.

References

Disaster Management Centre of Sri Lanka (DMC). 2025. Situation Reports: Cyclone Ditwah Flood Impacts.Colombo: Government of Sri Lanka.

Government of Sri Lanka. 2025. Preliminary Damage and Reconstruction Estimate Submitted to Development Partners. Colombo.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2024. Global Climate Finance Flows Annual Report.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2025. Geospatial Impact Assessment of Cyclone Ditwah.

World Bank. 2022. Urban Flood Resilience Planning Guidance.

— 2025. Internal Climate & Disaster Risk Briefing: South Asia Region.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2025. Sri Lanka Ditwah25 Emergency Situation Update. WHO South-East Asia Regional Office.

Green Climate Fund (GCF). 2025. Annual Report & Funding Commitments Summary.

(The author is a chartered architect by profession and currently a lecturer coordinating the capstone unit for Master of Sustainability course at the University of Sydney. She is specialised on biophilic sustainable design and a member of the NetZero Institute and Sydney Environment Institute. Her current research is on conducting integrated strategy analysis for NetZero transition. She has published in highly reputed academic journals and authored the book “A Biophilic Design Guide for Environmentally Sustainable Design Studio”. She developed Biophilic Living Cities framework that contributes to designing cities with nature-based solutions to improve sustainable performance and current secretary of Biophilic Cities Australia. She leads the Centre for Biophilic Design, and INZSTiL interdisciplinary online forums. She practices research-led sustainable architectural design, being a corporate member of the Sri Lanka institute of Architects, an International Chartered member of the Royal Institute of British Architects, accredited professional for Living Building Challenge and an Green building Council of Sri Lanka. She holds a postgraduate diploma on Interdisciplinary Design from the University of Cambridge, UK with a MPhil , MSc and BSc in architecture from the University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka. Apart from her professional work in architecture, research and education she is an artist and an advocate for animal rights.)

(The author is a chartered architect by profession and currently a lecturer coordinating the capstone unit for Master of Sustainability course at the University of Sydney. She is specialised on biophilic sustainable design and a member of the NetZero Institute and Sydney Environment Institute. Her current research is on conducting integrated strategy analysis for NetZero transition. She has published in highly reputed academic journals and authored the book “A Biophilic Design Guide for Environmentally Sustainable Design Studio”. She developed Biophilic Living Cities framework that contributes to designing cities with nature-based solutions to improve sustainable performance and current secretary of Biophilic Cities Australia. She leads the Centre for Biophilic Design, and INZSTiL interdisciplinary online forums. She practices research-led sustainable architectural design, being a corporate member of the Sri Lanka institute of Architects, an International Chartered member of the Royal Institute of British Architects, accredited professional for Living Building Challenge and an Green building Council of Sri Lanka. She holds a postgraduate diploma on Interdisciplinary Design from the University of Cambridge, UK with a MPhil , MSc and BSc in architecture from the University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka. Apart from her professional work in architecture, research and education she is an artist and an advocate for animal rights.)