Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Friday, 3 October 2025 01:26 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In the end, banks become the ultimate receivers of climate shocks, bearing the financial fallout of environmental catastrophes

The recent flash floods in Uttarakhand, India where over 100 people went missing, are just one among thousands of climate-related disasters in recent years. For banks, the impact is direct washed-out assets, loan defaults, and rising credit risk. This is not tomorrow’s threat; climate risk is already reshaping financial stability today. In the end, banks become the ultimate receivers of climate shocks, bearing the financial fallout of environmental catastrophes. Banking risk management is entering a new era. Traditional frameworks built around credit, market, liquidity, and operational risk are no longer sufficient to address the growing complexities of a changing world.

The recent flash floods in Uttarakhand, India where over 100 people went missing, are just one among thousands of climate-related disasters in recent years. For banks, the impact is direct washed-out assets, loan defaults, and rising credit risk. This is not tomorrow’s threat; climate risk is already reshaping financial stability today. In the end, banks become the ultimate receivers of climate shocks, bearing the financial fallout of environmental catastrophes. Banking risk management is entering a new era. Traditional frameworks built around credit, market, liquidity, and operational risk are no longer sufficient to address the growing complexities of a changing world.

Among the most disruptive forces is climate risk, which is rapidly emerging as a critical, system-wide challenge. I strongly believe despite increasing global awareness, many financial institutions have yet to fully grasp the gravity of climate risk and its potential to fundamentally reshape the financial landscape. The implications spanning credit risk, operational resilience, regulatory exposure, and reputational damage are often underestimated or overlooked. As climate related disruptions intensify, institutions that delay integration of climate risk into their governance and strategy may face systemic vulnerabilities, eroding stakeholder trust and losing access to global capital markets What makes it distinct is not just its severity or frequency, but its ability to reshape the entire risk landscape demanding a fundamental transformation in how banks assess, manage, and govern risk.

With my three decades of experience in banking and research across various subjects, including risk management, this article aims to provide an overview of how climate risk is poised to redefine banking risk management, potentially overtaking traditional risk areas in both significance and impact. To start with, as Mark Carney, then Governor of the Bank of England, famously said in 2015, “Climate risk is not just environmental it’s financial.” This statement marked a turning point in how global financial institutions began to view climate change not merely as an environmental concern, but as a systemic risk to financial stability and long-term economic resilience.

Climate risk demonstrate in two main forms:

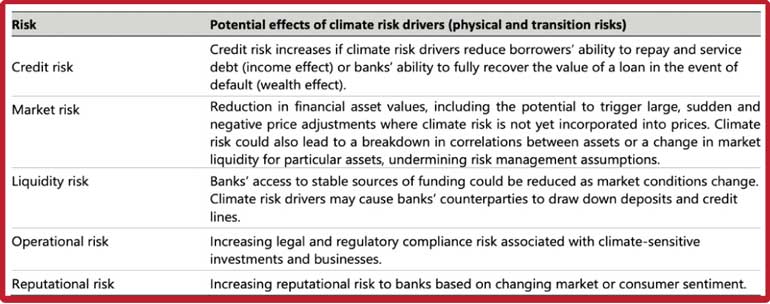

For banks, these risks can severely impact:

Due to physical damages (floods, droughts) or loss of value in carbon-intensive assets.

Borrowers in vulnerable sectors (e.g., agriculture, fossil fuels, real estate) may face default due to policy or physical risks.

Disruptions to branches, data centres, or supply chains due to extreme weather events.

Increased scrutiny from regulators, investors, and the public; failure to act may erode trust and share value.

Long-term assets becoming unviable due to new climate regulations or market shifts.

Global banks may terminate relationships with banks that fail to meet climate risk or ESG standards.

Increasing demands from central banks, supervisors, and standard setters (e.g., ISSB, NGFS, TCFD).

Capital buffers may be required for exposures to high-risk sectors under evolving prudential rules.

Physical risks make it harder and costlier to insure certain collateral or operational assets.

Legal action from shareholders, customers, NGOs or communities for financing environmentally harmful projects.

nMisalignment with ESG and sustainable finance markets

Difficulty accessing green bonds, sustainable finance facilities, or being included in ESG investment indices.

Investors may demand a premium or avoid banks not aligned with climate goals

This can result in delays in deploying green bond proceeds, leading to opportunity costs from idle funds.

Small businesses lacking adaptive capacity may face exclusion from credit, higher risk of failure, and informalisation impacting financial inclusion and national economic resilience

Younger workforce and stakeholders prefer working with and supporting climate-responsible institutions.

Traditional risk frameworks are not designed to handle this level of complexity. Climate risk is therefore poised to surpass traditional banking risks in significance. It is not merely an additional category, it is a risk amplifier that simultaneously magnifies credit, market, operational, and liquidity risks.

Climate risk is unique in critical ways:

1. It is systemic: It doesn’t just affect individual borrowers but entire sectors and geographies simultaneously

2. It spans multiple risk types simultaneously:

Climate risk impacts credit risk, market risk, operational risk, liquidity risk, and legal risk all at once, making it multifaceted and complex to manage.

3. It is forward-looking and uncertain: Unlike credit or market risk, climate risk doesn’t follow historical patterns.

4. It is deeply linked to reputation and stakeholder trust: Investors and the public increasingly scrutinise banks’ climate positions.

5. It is intensifying: With every delay in climate action, the risk compounds potentially creating sudden and nonlinear impacts

6. It can amplify social and economic inequalities:

Climate risk disproportionately affects vulnerable populations and businesses (e.g., MSMEs), potentially triggering broader socio-economic instability.

Key emerging changes in banking risk policy

Financial institutes are adding climate risk as a core component across credit, market and operational risk frameworks.

Credit underwriting, collateral valuation, and loan pricing now incorporate climate risk factors and ESG premium

Regulators require climate scenario stress tests to inform capital adequacy and resilience planning.

Banks set targets to cut high-emission exposures and boost green financing, adjusting risk limits accordingly.

If we further analyse the importance, integrating climate risk into the CAMELS framework enhances traditional bank risk management by embedding environmental vulnerabilities into core supervisory metrics. Each component of CAMELS Capital Adequacy, Asset Quality, Management Quality, Earnings, Liquidity, and Sensitivity can be directly influenced by climate-related physical and transition risks. Capital Adequacy must now account for potential losses from climate-exposed loans and stress scenarios. Asset Quality is impacted by the declining value of assets tied to carbon-intensive sectors or those vulnerable to natural disasters. Management Quality reflects how well a bank integrates climate risk into governance, policies, and enterprise risk management (ERM). Earnings can be affected by increased costs from climate compliance or reduced profitability from high-risk portfolios, while climate-related disruptions may challenge Liquidity through sudden funding pressures. Lastly, Sensitivity includes volatility from climate policy shifts, carbon pricing, and investor sentiment toward ESG performance. Embedding climate risks into CAMELS ensures a more resilient and forward-looking banking sector aligned with sustainability goals.

Conclusion

Climate risk is not just an emerging issue, it is a transformational force. As regulatory expectations tighten and environmental realities escalate, banks must shift from reactive compliance to proactive adaptation. Climate risk may not replace traditional risks immediately, but it is already reshaping how credit, market, and operational risks are understood and managed. This demands a change in thinking: policies, skills, and decision-making must evolve. Banks that make climate awareness a core part of their business will be the ones that remain strong in a climate-challenged world. If we fail to act now, climate risk will grow beyond the banking sector and become a national economic issue.

(The writer, holding a PhD, MBA, FIB, FCPM, MCIM, PgBFA, Dip.SF, is a senior banking professional with over 30 years of leadership experience in local and international banks. His expertise spans Retail, MSME, Corporate Banking, Risk Management, and Sustainable Finance, with a strong advocacy for green finance. He served as Vice President of the Association of Banking Sector Risk Professionals, Sri Lanka, where he played a key role in leading industry initiatives. He can be contacted via: [email protected].)