Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 5 March 2022 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The reason most freely bandied about for this crisis is the COVID pandemic. However, the reality is somewhat more complicated – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

By Dushyantha Mendis

That Sri Lanka is facing a very serious situation with regard to its foreign incomes and payments is obvious, with shortages arising at various times of, in particular, some food items, fuel for power stations, gas for domestic use, cement and medicinal drugs.

The reason most freely bandied about for this crisis is the COVID pandemic. However, the reality is somewhat more complicated.

Globally, recoveries from the COVID-related disruptions are in progress. Among developed countries, economies are recovering from the COVID-related disruptions at a fairly rapid pace. Taking Sri Lanka’s major export markets, the US is phasing out its monetary policy accommodations necessitated by the COVID disruptions, and the Federal Reserve is widely expected to raise interest rates in March this year. In the UK, the Bank of England has twice, in December 2021 and February 2022, increased interest rates. The eurozone economies are emerging into positive growth after a ‘double dip’ recession.

It is well known that recently Sri Lanka has had to seek accommodations in foreign exchange from Bangladesh, China, India and Pakistan. If those countries are able to help out, it means that they have the resources to do it, even while themselves coping with recovery from the COVID pandemic. This raises the question as to why Sri Lanka should be going with the begging bowl to her South Asian neighbours and to China.

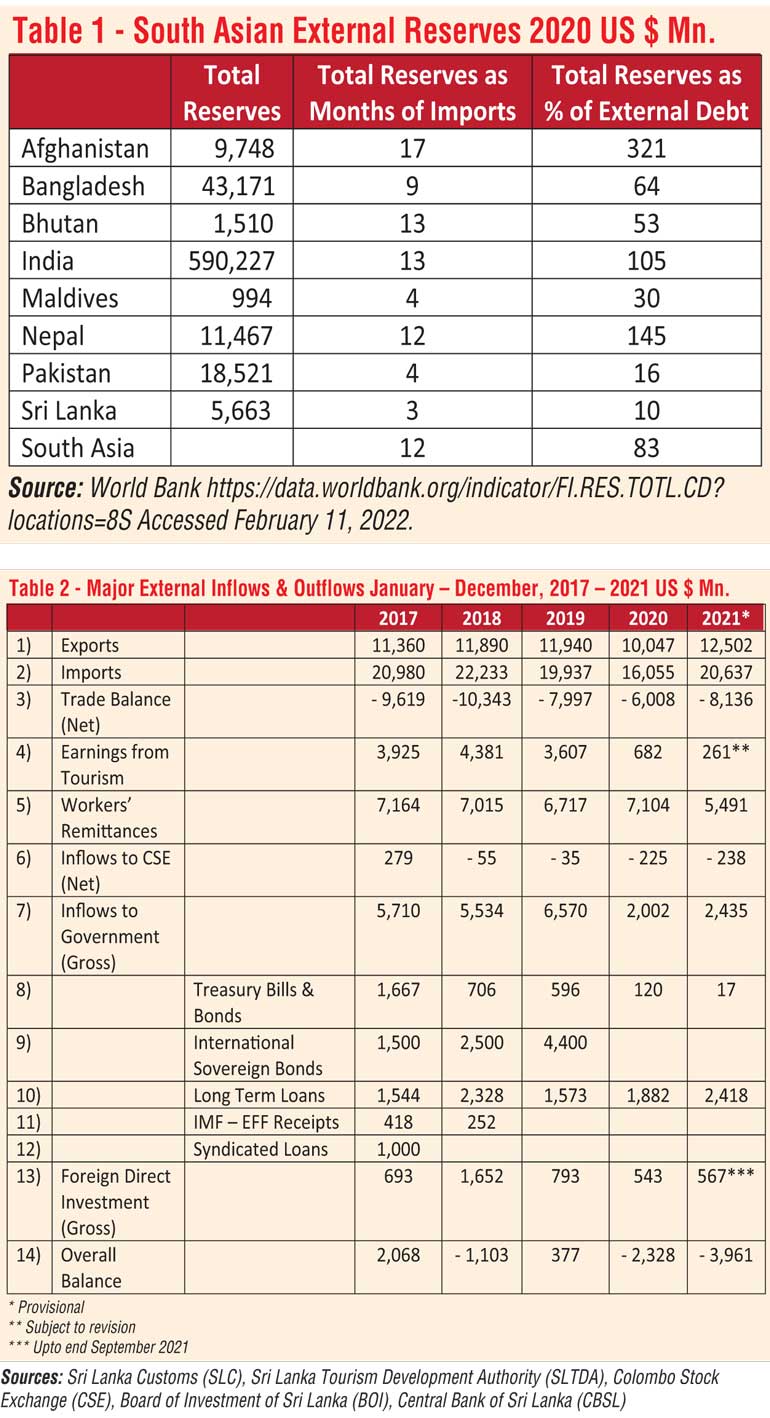

Table 1 indicates that where external finances are concerned, Sri Lanka is the South Asian basket case. Raw figures are interesting, but are not very useful unless related to some objective criteria. This is what is done in the last two columns of the table, where total reserves are seen in terms of months of imports and as percentages of external debt.

It is evident that Sri Lanka is at the bottom of the South Asian table, both literally and metaphorically, with averages far below that of South Asia

In this article, we shall argue that Sri Lanka is facing enormous problems in its external finances because of a fundamental structural weakness in its economy: the COVID-related disruptions made an already bad situation very much worse.

Table 2 provides sufficient statistical evidence to make our argument. The table is compiled from various issues of the Central Bank’s ‘External Sector Performance’, published every month. It sets out the most important external inflows to and outflows from the Sri Lankan economy.

Though there are some limitations, in that some items set out are net figures and others, gross figures, the table is sufficient to delineate some broad trends in the external sector of Sri Lanka. A full accounting for 2021 would have to await the release of the balance of payments table for 2021 in the Central Bank’s Annual Report for 2021, which could be expected to be released in April 2022. (The balance of payments table in the Central Bank’s ‘Recent Economic Developments’ published in October 2021 gives the figures only for the first six months of 2021). In the absence of that table, we make do with what comparable figures we have for the five years reviewed in the table

Of the five years included in the table, only two, 2017 and 2018 could be considered fairly typical or usual years, nothing out of the ordinary. 2019 was the year of the Easter Sunday bomb blasts, but the totally atypical years are 2020 and 2021, the years disrupted by the COVID pandemic.

Row 1 of the table, relating to exports is quite straightforward, but it must be borne in mind that exports themselves are to various degrees dependent on imported inputs. While the obvious case would be that of apparel exports, dependent on textile imports, even production and therefore export of tea, Sri Lanka’s major agricultural export, would to some extent be dependent on import of fertiliser and other agro chemicals.

The figures relating to exports show a steadily increasing progression from 2017 to 2019, a dip in 2020 and a stellar performance in 2021.

Imports – set out in Row 2 – rise in 2018 over 2017 levels, dip in 2019, dip very sharply in 2020 and bounce back to slightly less than the level of 2017 in 2021.

Row 3 sets out figures relating to the balance of trade, which is the difference between exports and imports. As could be seen, the balance of trade in all the years under review is negative, meaning that imports have consistently exceeded exports. Though the adverse balance of trade has declined sharply in 2020, it has exceeded the level of 2019 in 2021.

Row 4 sets out the earnings from tourism. These were in 2019 significantly reduced from the level of 2018, most likely due to the Easter Sunday bomb blasts. Taking 2019 as the base year however, they have plunged by $ 2,925 million in 2020 and $ 3,346 million in 2021, as a direct result of the COVID pandemic. In the five-year period reviewed in the table, the highest earnings from tourism are in 2018. If the figures for 2020 and 2021 are compared with the figure for 2018, the shortfalls in those years would be even greater.

Earnings from tourism can also be considered a gross figure because there are outflows related to the tourist sector, for instance for food items, hotel fittings, etc., fuel for tourist vehicles, and possible franchise payments by hotels belonging to international hotel chains.

Row 5 sets out inflows from Workers’ Remittances, and these have held up well even in 2020 but have declined in 2021 for reasons to be figured out, some other time. Workers’ remittances are to some extent gross inflows as expatriates working in Sri Lanka would be sending remittances abroad.

It would be noted that in the pre-pandemic years 2017-2019, the inflows from tourism and workers’ remittances combined have been sufficient to more than comfortably cover the adverse balance of trade. The two inflows combined have even covered the balance of trade in 2020. In 2021 however, the two inflows combined have been insufficient to cover the balance of trade.

Net inflows to the Colombo Stock Exchange – Row 6 – are hardly worth talking about even in pre-COVID years, and have been negative in 2020 and 2021, it may be remarked, even with a booming share market from the latter part of 2020 onwards through 2021! For all the hype about the share market, its contribution even in pre-COVID years to foreign exchange inflows has been even less than negligible. (However, it may be argued that ensuring foreign exchange inflows is not the role of the stock exchange, but would be a happy byproduct of its operations when positive inflows do take place.)

Gross inflows to Government, set out in Row 7, are of large magnitudes. Gross inflows to the Government indicate an increase in Government debt, as the quantum of such inflows received as grants is so small as to be almost microscopic.

It must be borne in mind that the statistics set out are gross inflows, and that the net figures, after accounting for repayment of capital and interest, would be smaller.

Gross inflows to Government have declined sharply in 2020 and 2021 as compared to the pre-COVID levels of 2017-2019. Taking 2019 as the base year, inflows to the Government have declined by $ 4,568 million in 2020, and $ 4,135 million in 2021. Perhaps 2019 is not a very good base year because of the quite extraordinary level of borrowings through International Sovereign Bonds in that year, but it would be readily seen from the table that inflows to the government in 2020 and 2021 are vastly below the levels of 2017 and 2018 as well.

Inflows to Government take place through various means:

Treasury bills are issued in maturities 91 days, 182 days and 364 days. Treasury bonds are issued for periods of more than one year. For instance, the notorious bond issue of February 27, 2015 was for a maturity period of 30 years. Both treasury bills and treasury bonds are issued in rupees, and yield foreign exchange inflows when foreign investors purchase them.

Taking 2019 as the base year, inflows from treasury bills and bonds have declined by $ 476 million in 2020 and by $ 579 million in 2021. Compared with the inflows from treasury bills and bonds in 2017 – US $ m 1667 – the shortfalls in 2020 and 2021 would be even greater.

International Sovereign Bonds (ISB) are denominated in US $, and are issued in international markets, with maturities of a minimum of five years. No ISBs have been floated in 2020 and 2021.

It would be noted that in the period 2017-2019, inflows from Treasury Bills and Bonds progressively decline, with increased amounts accruing from the issue of ISBs. The combined inflows from both these streams are $ 3,167 million in 2017, $ 3,206 million in 2018 and $ 4,996 million in 2019.

The decline in inflows to government securities and the inability to float ISBs in 2020 and 2021 would of course have other reasons besides the COVID-related disruptions, again to be figured out on another occasion.

Long-term loans would be from bilateral (government to government) sources or intergovernmental agencies such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, etc. This is the only category of inflows to Government which has increased in 2020 and 2021.

Inflows from the IMF, in any case very small, have ceased from 2019 onwards.

A type of inflow which is very much desired is foreign direct investment (FDI) – Row 13 – because it is associated with relatively large investments over a relatively short period of time, yielding quick gains in both production and employment. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka’s record in attracting FDI has always been relatively lacklustre, and such flows have declined fairly substantially in 2020 and 2021. Again, it is necessary to note that the figures given are gross figures, and the net figures, after deductions are made for repatriation of capital, profit and dividends from earlier investments, would be smaller.

The balance of payments table mentioned earlier, gives a comprehensive statement of all inflows and outflows categorised under different accounts.

When, in the balance of payments table, the total of all inflows is more than the total of all outflows, it is called a surplus in the balance of payments and is reflected in a positive change in reserves. When the total of all outflows is greater than the total of all inflows, it is called a deficit in the balance of payments and the deficit is met by a corresponding decline in reserves.

Thus, we come to Row 14, overall balance. This is the balancing item in the balance of payments, and states the changes in external reserves.

Of the five years 2017-2021, the overall balance has been positive only in two years, 2017 and 2019; the other three years have seen negative balances, which means that foreign reserves have been drawn down.

While the negative balance in 2018 was of a relatively small order, in 2020 and 2021, reserves have haemorrhaged, $ 2,328 million and $ 3,961 million respectively.

But look again more closely at the figures for the years when surpluses have been obtained; in 2017, the overall balance has increased by $ 2,068 million, only after inflows to the Government – basically Government debt – has increased by $ 5,710 million. Thus, the increase in reserves was obtained in large part by an increase in gross government debt.

That is the case in 2019 as well, but here the situation is even worse: an increase in reserves of $ 377 million has been obtained only after an increase in gross government debt of $ 6,570 million.

Thus, a good part of external reserves would not be free, or as the Central Bank likes to call them, ‘organic’ resources as such, but borrowed resources.

In the three years when the overall surplus was in deficit, 2018, 2020 and 2021, we have already noted that reserves were drawn down, but the reserves themselves would have included a heavy share of earlier borrowings.

The point that the external reserve position of Sri Lanka is dependent to some significant degree on government debt is worth driving into the ground through quotations from the Central Bank reports for 2017 and 2019, the years in which the overall balance recorded surpluses.

Central Bank Annual Report 2017

p. 172

Significant inflows to the financial account, including the proceeds of the ISB, proceeds from the foreign currency term financing facility, net project and programme loans received by the government, issuance of Sri Lanka Development Bonds and a significant net absorption of foreign exchange by the Central Bank resulted in net international reserves increasing to US dollars 6,597 million by end-2017 from US dollars 4,529 million at end-2016. Consequently, the overall balance, which is also the difference between the change in net international reserves during the two periods, amounted to US dollars 2,068 million in 2017 …

Central Bank Annual Report 2019

p. 195

The overall balance, which is equal to the change in net international reserves, recorded a surplus in 2019 in contrast to the deficit recorded in 2018. Significant inflows to the financial account during the year in terms of proceeds of the ISBs resulted in an increase in net international reserves, amounting to US dollars 5,871 million at end 2019, from US dollars 5,495 million at end 2018. Consequently, the overall balance recorded a surplus of US dollars 377 million in 2019, in comparison to the deficit of US dollars 1,103 million recorded

in 2018.

If that was the position when the overall balance recorded surpluses, the position when the overall balance was in deficit may be readily comprehended.

This is the structural weakness of the external sector of the Sri Lankan economy even prior to the COVID pandemic, that it is hooked on inflows of debt obtained by the Government: inflows from exports, tourism, workers’ remittances and FDI simply do not suffice to make ends meet.

It is easy to now understand the havoc of 2020 and 2021; the decline in the receipts from tourism have been combined with significantly reduced inflows to Government.

It is no wonder therefore that external reserves have haemorrhaged in 2020 and 2021.

To summarise, we may note, allowing ourselves to use two consecutive metaphors in the same sentence, that if we are now thrown on the rocks, it is because we had been sailing very close to the wind for quite some time.

To be continued.

(Dushyantha Mendis holds a BA Hons. degree in Economics from the University of Peradeniya, an LLB from the Open University of Sri Lanka, and is an Attorney-at-Law. He welcomes readers’ comments at [email protected].)