Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Wednesday, 13 July 2022 00:40 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Forming and sustaining an all-party government is crucial for Sri Lanka at this stage. IMF support which the country awaits eagerly depends on certain conditionalities. These conditionalities sound simple enough – increase government revenue, reduce expenditure, and provide social safety nets for the most vulnerable, but devil would be in the detail. Thrashing out the details cannot be business as usual where a governing party formulates and then brings to parliament.

Forming and sustaining an all-party government is crucial for Sri Lanka at this stage. IMF support which the country awaits eagerly depends on certain conditionalities. These conditionalities sound simple enough – increase government revenue, reduce expenditure, and provide social safety nets for the most vulnerable, but devil would be in the detail. Thrashing out the details cannot be business as usual where a governing party formulates and then brings to parliament.

We have a highly fragmented Parliament, and it will continue to fragment with more and more MPs choosing to be independents. Coalitions will form and break. It will be hard to distinguish a governing party and an opposition, as in the Westminster style. A new mode of parliamentary governance is needed.

Groups of opposition MPS are already working on a common minimum program around which parties can be rallied. But is that enough? To be an all-party one, the coalition would have to be a big one with a majority of parties in Parliament, if not all, represented. How will such a coalition share responsibilities. Should not there be some understanding about the minimum number of ministerial portfolios required so that we don’t have a bloated cabinet or disappointed coalition partners?

How will a coalition work out the messy details of a common minimum program? How can we avoid disappointment and bitterness of coalition partners left out of the decision-making? A quote by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike on the executive committee system during the governments under the Donoughmore Constitution from 1931-1947 might be relevant here:

“In countries where you cannot really hope to get two parties to divide on purely political issues, there should be a modification of the system where all MPs regardless of party have some share in executive work. Under the Donoughmore Constitution, backbenchers of all parties shared executive work and you avoided the bitterness and the sense of frustration that is liable to develop not only among the opposition parties, but even backbenchers of the Government. There were defects in the Executive Committee system as it was worked in Ceylon, but it has always been my view that it was a mistake to have scrapped it altogether.” [Quote from S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike in Russel, 1982, p. 214]

A fourth issue is role to be played by civilians, especially the youth who took to the streets to bring an end to the Rajapaksa regime. You can’t expect them to sit back and be mere spectators of critical post-Rajapaksa developments.

Taking these issues into consideration and synthesising arguments put forward by others and the author’s own work, I’d like to put forward the following four essentials for forming and sustaining an all-party government. Namely,

These may not be all but let’s start with these.

A Common Minimum Program (CMP)

A Common Minimum Program (CMP)

Various groups including political parties have produced action programs for an interim government. The National Movement for Social Justice compiled a common minimum program capturing commonalties across these proposals. As tweeted by Harsha de Silva, there is already consensus by a significant group of parliamentarians in the opposition for an economic stabilisation program.

Aragalaya youth have also presented their demands at various occasions. They are no longer shunning political parties and discussions are underway between them and the political parties. At this stage, a common minimum program is the lowest hanging fruit. The structures we need for working out the details and implementing them are the harder ones. Next three essentials are about these structural features.

A rationalised set of Cabinet portfolios

The interim Cabinet of Gotabaya Rajapaksa that functioned from the presidential election in November 2019 to the general election in August 2020 had only 15 Ministers. This was immediately expanded after the general election to the full set of 30 cabinet ministers plus the set of 40 state ministers allowed in the Constitution, but the interim portfolio of 15 is evidence that it can be done.

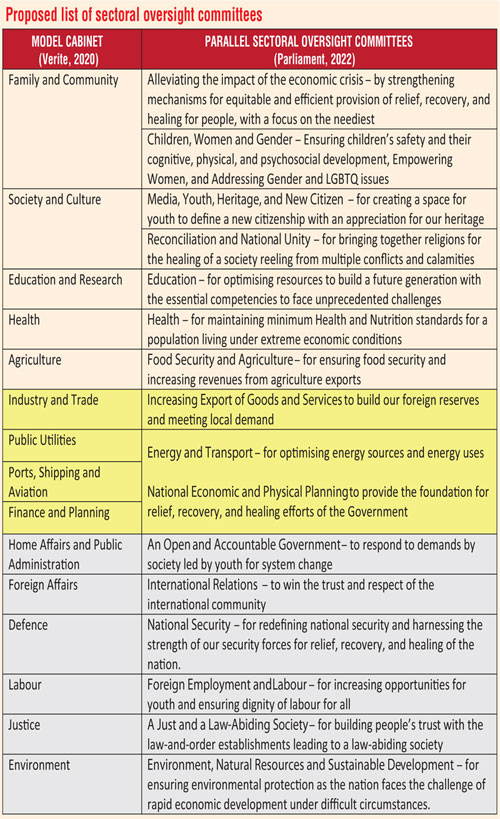

Today, not only do we have an interim situation, but we also have a severe and prolonged economic crisis where optimum performance of Government is critical. As Verite research has argued in their 2020 paper on a rationalised cabinet for Sri Lanka, for optimum performance of Government we need to minimise fragmentation or misalignment of sectors which concern the Government. The model cabinet proposed by Verite Research is a result of a detailed analysis aiming for the least amount of fragmentation and misalignment of 15 identified sectors. This list of 15 sectors is also the prescribed list of cabinet portfolios. The list of sectors includes the following:

1. Family and Community; 2. Society and Culture 3. Education and Research 4. Health 5. Agriculture 6. Industry and Trade 7. Public Utilities 8. Ports, Shipping and Aviation 9. Finance and Planning 10. Home Affairs and Public Administration 11. Foreign Affairs 12. Defence 13. Labour 14. Justice and 15. Environment

Each sector may have two or more subjects under each. We have renamed the Economic Affairs sector as the Industry and Trade to directly represent the subjects under that sector. The prescribed rule for avoiding fragmentation or misalignment of sectors is to stay within a sector when you mix and match subjects.

This list of sectors is indeed what you find common to all cabinets across the world though they may not use the same terms. The list order of the cabinet portfolios typically begins with finance, defence, foreign affairs, etc., but soon becomes a random ordering. Here, I started with sectors with more or less direct impact on society (1-6), then added those with more or less direct impact on the economy next (6-9), and placed other sectors which form the foundation for the functioning of those nine sectors last (10-15).

To convince an all-party coalition to agree to a rationalised cabinet of fifteen portfolios (ideally without state ministries), the committees in Parliament must be made more attractive options for MPs.

A high-powered committee system in Parliament

Our Parliament already has a committee system established by the standing orders of the Parliament. We also have the experience of an executive committee system that functioned under the Donoughmore Constitution of 1931-1947. Overall, committees have proven to be venues where members of parliament get a chance to engage in reasoned arguments unlike the rhetorical posturing often seen on the house floor. There are special advantages to each type of committee as well.

In Chapter 5 of his book titled ‘Power-sharing in the regions’ Jayampathy Wickramaratne notes that: “A system of executive committees existed under the [Donoughmore Constitution which was operative] from 1931 to 1947 in pre-independent Ceylon… The absence of political parties would have made a cabinet form of Government difficult and executive committees allowed for the participation of minorities in Government…”

This note about the relevance of executive system in the absence of political parties further supports Bandaranaike’s comments quoted before.

More recent examples from recent Parliament too point to the importance of á strong committee system. The Sectoral Oversight Committees (SOCs) set up by the 8th parliament of the 2015-2020 period has sweeping powers as defined by House Standing Order 111 – i.e. “general oversight responsibilities in order to assist Parliament in: (a) its analysis, appraisal and evaluation of the application, administration, execution and effectiveness of legislation passed by Parliament and conditions and circumstances that may indicate the necessity or desirability of enacting any new or additional legislation; and (b) its formulation, consideration and enactment or changes in any law and of such additional legislation as may be necessary or appropriate”.

Some of the Chairmen of these sectoral oversight committees used them well to develop comprehensive policy papers or intervened to resolve thorny issues of implementation and they speak glowingly of the value of these committees but point out the difficulties as well.

For example, the Women and Gender committee which was chaired by Thusitha Wijemanna brought up the issues of sex education, minimum marriage age and discriminatory line asking whether the parents are married on the birth certificate. The committee managed to resolve the last issue, but the other two issues could not be brought to a resolution because of the lack of commitment of the ministers concerned and the turbulence of the last two years of the Yahapalana Government.

In another plus for the committee system, the sectoral committees allow younger MPs with fire in their belly to hold the chairmanship in these committees and show their colours. This is particularly important in Sri Lanka where senior politicians expect to receive cabinet appointments no matter their lack of performance in previous positions.

A proposal tabled in the Parliament on 5 June 2020, by the PM to revitalise the sectoral oversight committees has a list of 16 sectoral committees which is closely aligned with the list from the previous 8th Parliament but the emphases have been changed to reflect the burning needs of the country in the next many years. This list is also mapped to the rationalised list of Cabinet portfolios developed by Verite Research so that there is close alignment between cabinet portfolios and sectoral committees, and the portfolios or the sectoral committees can be broken up or put together as needed with minimum fragmentation or misalignment of sectors.

Proposed list of sectoral oversight committees

Other relevant committees in the present Parliament are the Consultative Committees which have been in existence since 1978-2018 simply as consultative committees. With the advent of sectoral oversight committees, the scope of these consultative committees were reduced in 2018 and renamed as Ministerial Consultative Committees.

The 9th Parliament led by the Rajapaksas, allowed the sectoral oversight committees to lapse but the default Ministerial Consultative Committees were not strengthened to fill the gap. According to Standing Order 112 relevant to these committees, the Cabinet minister in Charge was the chairman and the membership consisted of any state minister or deputy minister and five additional members to be nominated by the Committees on Selections. These consultative meetings largely addressed issues at electorate level with larger sectoral issues not receiving due attention during 2020 to date.

The way forward could be a hybrid of the oversight and executive models for the duration of the interim Government where sectoral oversight committees are chaired by the minister in charge, but all subjects are distributed among sub committees with a non-cabinet chairperson for each. And all Committees have multi-party representation. The minister’s role would as facilitator in chief who would coordinate the work of sub committees and present a coherent set of policies which have bipartisan support to the cabinet for final approval and implementation. The sub-committee chairs will continue to play a role in monitoring the implementation.

In Chapter 5 of his book titled ‘Power-sharing in the regions’, Jayampathy Wickramaratne notes that the executive committee system under the Donoughmore Constitution allowed for a more participatory decision making in that Parliament.

“Board of Ministers [or Cabinet] under the Donoughmore Constitution did not constitute a homogeneous group having the same or similar political opinion like the customary British Cabinet. Ministers did not carry out some part of a consistent, coordinated Cabinet policy but acted as rapporteurs of the decisions of executive committees. There had even been instances of Ministers speaking and voting on opposite sides.”

With only less than year anticipated for the duration of an interim Government in the context of an extremely fragmented Parliament, A high-powered committee system that distributes power could be the only way out.

Representation for youth in the interim government

Those who risked their lives to oust the Rajapaksas have already expressed their demands for a say in an interim government. Constitutionally there are no provisions, but the Committee system is one where youth or any group of civilians can be included as a permanent but non-MP members through changes to standing orders. It is Ranil Wickremesinghe who first proposed that 4-5 youth should be brought into the committee system and asked the assistance of Karu Jayasuriya, former speaker of the Parliament to identify a mechanism. Ironically, his resignation is now demanded along with Rajapaksas with equal vehemence by the protestors.

More on representation for youth in an all-party interim government in the next column.