Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Monday, 5 January 2026 02:03 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

If you want to change a country, change the classroom

If you want to change a country, change the classroom

Education is not simply about literacy or exams—it is the architecture of a nation's future. The classroom is where values are seeded, identities are shaped, and competencies are built. Every reform, every textbook, every policy is a message about the kind of society a Government intends to leave behind.

That is why Sri Lanka's recent Grade 6 textbook scandal is so alarming. A module intended to teach English contained a live link to buddy.net, an adult dating site. What should have been a harmless exercise in self-description became a digital doorway into predation. This was not a minor editorial slip. It was a breach of trust, a violation of child psychology, and a collapse of institutional safeguarding.

Governments must ask themselves: when they leave office, what do they leave behind? A generation empowered with critical thinking, empathy, and digital safety—or a generation scarred by exposure, exploitation, and mistrust in the very institutions meant to protect them?

The psychology of protection

At age 11–12, children are in Erikson's industry vs. inferiority stage, where competence and self-esteem are paramount. Exposure to adult sexual environments undermines confidence, creating confusion and anxiety. UNICEF's Safety by Design principle requires that educational materials anticipate and eliminate risks before they reach children. The buddy.net incident violated every safeguard.

Parents and children rely on trusted institutions—schools, teachers, textbooks—as secure guides. When those fail, the breach erodes trust and can trigger long-term insecurity. Protecting childhood is not an optional extra; it is the foundation of resilience.

Global policy shifts

Sri Lanka's scandal is part of a wider debate. In late 2025, Italy's Government under Giorgia Meloni banned LGBTQ topics in primary schools and required parental consent in secondary schools. Supporters argue this protects parental rights; critics see it as censorship. Hungary, Bulgaria and several US states have enacted similar restrictions.

The common thread is the contested nature of the classroom. Governments are redefining education as a battleground between parental authority, state policy, and child rights. The question is not only what children learn, but who decides.

The digital pandemic

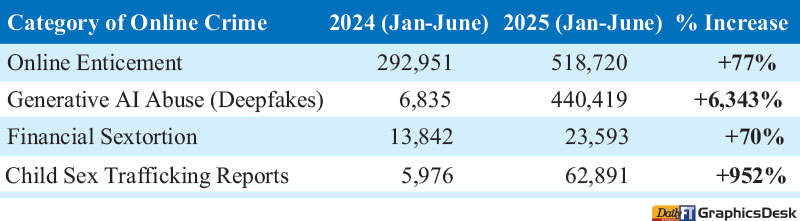

The classroom crisis is magnified by the rise of online predation. Data from the US National Center for Missing & Exploited Children shows staggering increases between just the first half of 2024 and the first half of 2025:

Predators exploit gaming platforms like Roblox, educational portals, and even school resources. The use of generative AI has become a "hidden pandemic," where predators create fake explicit images of children using photos taken from social media or school websites to blackmail them.

Since 2021, at least 36 teenage boys have taken their own lives because they were victimised by sextortion. They are not statistics—they are sons, brothers, students who saw no way out when predators threatened to destroy their lives by sharing manipulated images.

A textbook link to an adult site is not just inappropriate—it is a gateway into this global crisis. The buddy.net incident in Sri Lanka created what experts call a "Digital Doorway" to several crimes: financial sextortion, deepfake abuse, and direct contact with predators on a site designed for adult sexual encounters.

Devices, data and the 4Cs

Governments are responding with device bans and stricter digital hygiene. By the end of 2024, approximately 40% of the world's education systems had implemented some form of smartphone ban. France and the UK have introduced "bell-to-bell" bans, where students must surrender phones at the start of the day. UNESCO reports that removing smartphones improves learning outcomes and reduces "brain drain," particularly for students already struggling academically. Beyond preventing distractions, these bans shield children from data harvesting by apps and reduce opportunities for peer-to-peer cyberbullying and the sharing of non-consensual images.

Educators now use the 4Cs risk framework to justify restrictions:

Sri Lanka’s textbook incident triggered all four risks simultaneously. The buddy.net link exposed children to adult sexual content (Content), potentially connected them with predators on a platform designed for adult hookups (Contact), could lead to coercion and sextortion (Conduct), and likely compromised their digital privacy through an unregulated site (Contract).

Institutional negligence and loss of trust

The outrage in Sri Lankan Government stems not only from the danger but from the breakdown of quality control. How could a panel of experts approve a textbook without a simple web check? The buddy.net site is not ambiguously named—it is an active website designed for adult men to find gay partners and hookups, featuring content related to “cruising” and sexual encounters.

The scale of this near-catastrophe is staggering: 400,000 copies of the textbook were printed and ready for distribution. That represents 400,000 children—an entire generation of Grade 6 students—who could have been directed to an adult dating site by their Government-approved learning materials. The fact that the error was caught before full distribution does not absolve the institutional failure; it merely prevented a disaster from becoming a national tragedy. ( Website Linked in School Textbook Blocked as Education Row Sparks Political Fallout - LNW Lanka News Web )

How did this happen? The Ministry of Education has lodged a complaint with the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), and the National Institute of Education (NIE) is conducting an internal inquiry. The head of NIE, Manjula Vithanapathirana, has resigned pending investigations. Yet these reactive measures raise a more fundamental question: Why weren’t safeguards in place to prevent this from happening in the first place? Isn’t it obvious that such a inclusion would have had directives?

The investigation now focuses on whether this was deliberate sabotage or catastrophic negligence – or an institutional cover up? Either answer is damning. If sabotage, it reveals that Sri Lanka’s curriculum development process is vulnerable to malicious actors who can weaponise textbooks against children. If negligence, it shows that basic quality control—a simple web search before printing 400,000 books—has collapsed entirely. If it ends up as a cover up then it is worse.

The Ministry of Education now faces a credibility crisis. Recent education reforms, regardless of their intent, are undermined when the very institutions implementing them cannot be trusted to keep children safe. The ministry’s accountability extends beyond this single incident—it must answer for the systematic failure of oversight that allowed an adult dating site to be printed in children’s textbooks.

The dangers of this inclusion

are severe:

1.Exposure to adult and explicit content: At age 11-12, children are cognitively and emotionally unprepared for such material. This is a direct violation of educational psychology principles.

2.Gateway to online grooming: The site is a social platform where adults interact. A child following a school-sanctioned link enters a space where predators can easily identify them as a minor and begin grooming.

3.“Digital Doorway” to cybercrime: Predators on such sites often move conversations to encrypted apps like Snapchat or Telegram for blackmail. They can also scrape a child’s profile to create AI-generated explicit images.

4.Resource waste and erosion of trust: Rectifying the error requires recalling thousands of printed books and blocking the site nationally through the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission of Sri Lanka (TRCSL), wasting massive public funds and eroding public confidence in the education system.

This is more than a local scandal. It is a violation of UNICEF child protection principles and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Educational materials are legally and ethically expected to be “Child-Safe by Design.” Directing children to an adult environment bypasses every standard of institutional safeguarding:

This is a psychological breach of trust, exposing children to adult environments at the exact developmental stage when they are forming identity and competence. And it is a loss of institutional credibility, showing how fragile oversight has become in the digital age.

What happens next: Breaking the cycle of institutional failure

The buddy.net scandal demands more than investigations and resignations. It requires systemic reform to ensure this never happens again—in Sri Lanka or anywhere else. Governments cannot afford reactive crisis management when children’s safety is at stake.

Essential reforms must include:

1. Mandatory digital hygiene protocols: Every URL, QR code, and web reference in educational materials must undergo verification before approval. This is not optional—it is baseline child protection.

2. Independent third-party vetting: Curriculum materials should be reviewed by external child safety experts who are not embedded in the ministry’s internal processes. Fresh eyes catch what familiarity misses.

3. Regular audits and red-teaming: Educational materials should be subject to periodic “hostile review”—asking not “what could go right” but “what could go wrong?” This includes testing all digital links annually, as websites change ownership and content.

4. Training for curriculum developers: Every person involved in creating educational materials must complete certified training in child safeguarding, digital literacy, and age-appropriate content standards.

5. Transparent accountability frameworks: When failures occur, the public deserves clear answers: Who approved this? What checks were missed? What consequences follow? Without transparency, trust cannot be rebuilt.

6. Integration of digital safety into curricula: Children must learn to identify unsafe websites, recognise grooming tactics, and understand their rights online. If textbooks can fail them, they need the skills to protect themselves.

These are not aspirational goals—they are minimum standards that every education system must meet in the digital age. The cost of implementing these safeguards is negligible compared to the cost of failing to protect even one child.

The exodus: When parents lose faith in the system worldwide

When institutions fail children, parents make a choice. And increasingly, across every continent, that choice is to leave the system entirely. This is not an American phenomenon—it is a global reckoning.

The numbers tell the story of a worldwide crisis of confidence:

In the United States, homeschooling enrollment surged 51% from 2.5 million students in 2019 to over 3.7 million in 2024-2025, growing at 5.4%—nearly triple the pre-pandemic rate. The United Kingdom now has over 111,700 homeschooled children as of autumn 2024, representing a 40% increase over three years, with some regions seeing a 71% increase in secondary school students moving to home education. Australia’s homeschooling population exploded to over 45,000 students in 2024, with Queensland alone tripling its numbers since 2019. Even in Poland, where homeschooling was relatively rare, the numbers skyrocketed from 10,976 students in 2019-20 to 54,936 by February 2024—a 400% increase in just four years.

The global homeschooling market itself—valued at $3.59 billion in 2023—is projected to reach $8.95 billion by 2032, growing at 10.68% annually. This isn’t niche anymore. This is mainstream exodus.

The reasons parents cite are damning: The number one driver globally isn’t religious instruction or academic preference—it’s concern about the school environment, including safety, drugs, and negative peer pressure. In the UK, the most reported reasons for electing home education are “mental health” (14%) and “philosophical or preferential reasons” (14%). Translation: parents no longer trust schools to protect their children’s wellbeing.

The data mirrors a cascading trust crisis: 59% of school parents in the U.S. now say K-12 education is headed in the wrong direction, up from 52% in 2021. Dissatisfaction with traditional schooling systems, overcrowded classrooms, and concerns about child safety are driving parents in India, China, Australia, France, Mexico, Japan, South Korea, Russia, and beyond to explore alternatives.

This is a cross-cultural, cross-continental movement. It is happening in countries with strict regulations (like Poland and parts of Europe) and in countries with relaxed frameworks (like the UK and Australia). It is happening among secular families and religious ones. It is happening in wealthy nations and developing ones. The common thread is universal: institutional failure breeds parental flight.

Even in Sri Lanka, where homeschooling remains less common than in Western countries, the community is growing—particularly among families seeking personalised education and greater control over their children’s learning environment. The cultural shift may be slower, but it follows the same inexorable pattern: when trust erodes, parents seek alternatives.

Sri Lanka’s textbook scandal is exactly the kind of institutional failure that accelerates this global exodus. When a Government-approved textbook directs children to an adult dating site, it doesn’t just confirm Sri Lankan parents’ worst fears—it sends a signal to parents worldwide: The system designed to protect children is fundamentally broken. Quality control has collapsed. Oversight has failed. And children are the collateral damage.

France bans smartphones in schools. Italy restricts curriculum content. Hungary tightens regulations. But none of these policy fights address the deeper rot: Governments are debating what to teach while failing at the most basic obligation—keeping children safe from predators, whether those predators are lurking online or printed in textbooks approved by education ministries.

The homeschooling surge isn’t about rejecting education—it’s about reclaiming responsibility when institutions prove they cannot be trusted with it. It’s millions of parents across dozens of countries saying in dozens of languages: “If you won’t protect my child, I will.”

And they are acting on it—at a scale and pace that should terrify every education ministry on Earth.

Conclusion: Protecting childhood as legacy

Education is legacy. It is the one institution that outlives Governments, shaping the citizens who will inherit the nation. When classrooms fail, children pay the price—confusion, exploitation, and erosion of trust in the very institutions meant to protect them.

Sri Lanka’s scandal is a wake-up call. In a world of rising cybercrime and contested curricula, Governments cannot afford negligence. Protecting children means respecting their psychological stages, safeguarding their trust in institutions, and designing education that nurtures rather than endangers.

Resilience without strategy is erosion. And in education, erosion begins the moment we fail to protect the child.

If you want to change a country, change the classroom. If you want to destroy it, neglect the child.

(The author began his career in the banking sector, where he built an illustrious track record before transitioning into education in 2007. Since then, he has held senior leadership roles including Regional Director of CIMA and Executive Director of IIHE, while also serving as a lecturer for MBA programs across both local and British universities. Bradley has contributed directly to national education policy, serving on two Education Reform Commissions under Minister S.B. Dissanayake and Minister Susil Premjayantha. His work bridges practice and policy, combining strategic leadership with a commitment to shaping classrooms as engines of national transformation. He could be reached via email at [email protected])