Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Friday, 2 January 2026 00:23 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

This article is Part II of the article published under the same headline with a broader analysis of the events surrounding Cyclone Ditwah, with particular emphasis on the roles and responsibilities of relevant Government agencies, as well as the collective responsibility of the public, in managing and mitigating the impacts of the disaster.

This article is Part II of the article published under the same headline with a broader analysis of the events surrounding Cyclone Ditwah, with particular emphasis on the roles and responsibilities of relevant Government agencies, as well as the collective responsibility of the public, in managing and mitigating the impacts of the disaster.

Role of the National Building Research Organisation (NBRO)

The NBRO issues highly accurate early warnings by integrating meteorological data with its own landslide early‑warning sensor networks and computer‑based models. Japan’s JICA has repeatedly supported the NBRO with advanced equipment and specialised training. Although the NBRO’s landslide division operates with limited staff, it has implemented effective mitigation measures in hilly regions and along major road networks.

However, protecting individuals who live in extremely unsafe conditions on steep hilltops cannot be the sole responsibility of the NBRO. As a first step, no construction approvals should be granted in officially designated landslide‑prone zones. Environmentally destructive projects and soil‑eroding agricultural practices in highland areas must also be strictly prohibited.

Role of the Disaster Management Centre (DMC)

The Disaster Management Centre comprises officers seconded from the tri‑forces, police, and other services, as well as civilian officials. Upon receiving early warnings, the DMC immediately alerts all District Disaster Management Committees and places lifesaving units on standby. Maintaining uninterrupted 24‑hour communication systems is essential during emergencies, and District Committees remain in continuous contact with the DMC’s central operations room in Colombo.

The DMC also plays a vital role in community education. Recently, in collaboration with the Department of Meteorology and other agencies, it conducted a tsunami preparedness drill that significantly improved awareness among coastal communities.

The DMC also plays a vital role in community education. Recently, in collaboration with the Department of Meteorology and other agencies, it conducted a tsunami preparedness drill that significantly improved awareness among coastal communities.

However, during severe disasters, communication and power infrastructure often fail, as occurred during Cyclone Ditwah, when terrestrial communication systems were severely disrupted. Managing disasters under such conditions becomes extremely challenging, underscoring the urgent need for satellite‑based communication systems.

Tragically, during relief operations in Nattandiya, a Sri Lanka Air Force helicopter crashed, killing a highly experienced squadron leader. Naval personnel, an army soldier, a police officer, and a Ceylon Electricity Board technical officer also lost their lives during rescue and reconstruction efforts. These sacrifices are beyond any monetary valuation.

The reconstruction phase

Sri Lanka has now entered the national reconstruction phase. Countries such as Japan, Indonesia, and New Zealand have demonstrated that recovery from major natural disasters is possible through structured, sustainable interventions and strong legal frameworks. While these responsibilities rest primarily with the Government, rapid recovery is achievable when the State and the public work together with a shared sense of responsibility.

This disaster struck while the country was still emerging from the severe economic crisis of 2022. Yet the immediate response has been encouraging: volunteer groups, organisations, and the tri‑forces mobilised swiftly. Severely damaged bridges, roads, railway lines, canals, weirs, and reservoir embankments are already being restored at an impressive pace. The dedication of these teams reflects the enduring national spirit often celebrated in Sri Lanka’s historical narratives.

Many public servants have worked far beyond their standard duty hours, collaborating closely with volunteer groups which is an unmistakable sign of national commitment. As citizens, it is equally important that we resume economic and social activities promptly. International assistance, while invaluable, cannot continue indefinitely. In the coming years, work must proceed without strikes or disruptions, and the Government must act responsibly without imposing undue burdens on the public. Political differences must be set aside in favour of collective national effort.

Key proposals for the future

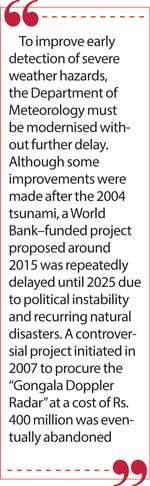

To improve early detection of severe weather hazards, the Department of Meteorology must be modernised without further delay. Although some improvements were made after the 2004 tsunami, a World Bank–funded project proposed around 2015 was repeatedly delayed until 2025 due to political instability and recurring natural disasters.

A controversial project initiated in 2007 to procure the “Gongala Doppler Radar” at a cost of Rs. 400 million was eventually abandoned. The radar, to be purchased from Enterprise Electronics Corporation (EEC) in Alabama, USA, with technical support from the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), failed during factory acceptance testing in 2010. Despite this failure, a senior official intervened to have the defective system shipped to Sri Lanka.

Installation plans were further disrupted when a crane (planned to use installation of the radar’s heavy antenna) fell enroute to the Gongala mountain top, damaging the access road. After months of repairs, EEC engineers inspected the stored components and refused to proceed with installation. The WMO was notified, and UNOPS conducted an independent inspection. Although the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption began an inquiry in 2016, investigations were later halted. The Committee on Public Accounts (COPA) also raised concerns. Some defective components were reportedly shipped back to the United States at additional cost, but there is no evidence they were repaired or returned. Several components stored at Gongala were later stolen, and although a police complaint was filed, no resolution has been reported.

Installation plans were further disrupted when a crane (planned to use installation of the radar’s heavy antenna) fell enroute to the Gongala mountain top, damaging the access road. After months of repairs, EEC engineers inspected the stored components and refused to proceed with installation. The WMO was notified, and UNOPS conducted an independent inspection. Although the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption began an inquiry in 2016, investigations were later halted. The Committee on Public Accounts (COPA) also raised concerns. Some defective components were reportedly shipped back to the United States at additional cost, but there is no evidence they were repaired or returned. Several components stored at Gongala were later stolen, and although a police complaint was filed, no resolution has been reported.

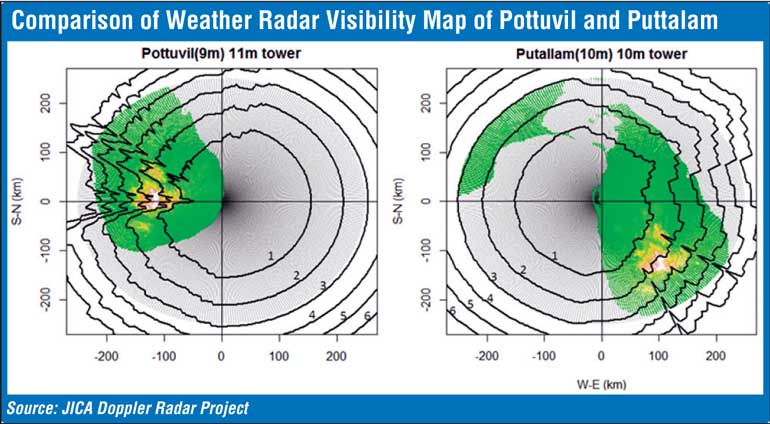

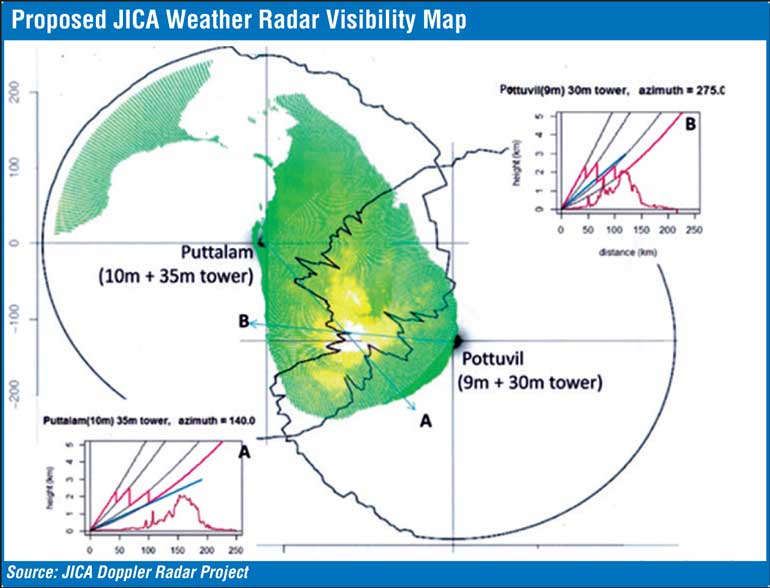

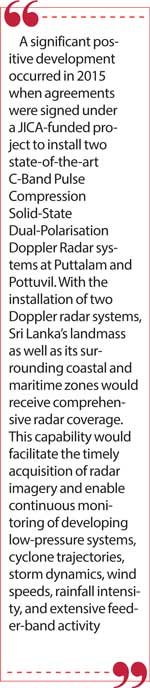

A significant positive development occurred in 2015 when agreements were signed under a JICA‑funded project to install two state‑of‑the‑art C‑Band Pulse Compression Solid‑State Dual‑Polarisation Doppler Radar systems at Puttalam and Pottuvil.

With the installation of these two Doppler radar systems, Sri Lanka’s landmass as well as its surrounding coastal and maritime zones would receive comprehensive radar coverage. This capability would facilitate the timely acquisition of radar imagery and enable continuous monitoring of developing low‑pressure systems, cyclone trajectories, storm dynamics, wind speeds, rainfall intensity, and extensive feeder‑band activity.

From the earliest stages of cyclone formation, Doppler radar functions as an essential forecasting tool, providing accurate, continuous, high‑resolution observations even when cyclonic systems are located up to approximately 300 kilometres away. Such capacity is vital for enhancing the accuracy of early warnings and extending lead times for preparedness and response in addition to Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) techniques.

However, precise quantitative rainfall forecasting ultimately requires the validation and calibration of radar‑derived estimates against ground‑based measurements. This process depends on reliable data from the Department’s network of automatic rain gauges, which are indispensable for verifying and refining precipitation forecasts from a radar system.

An examination of cyclones, severe cyclonic storms, and intense low‑pressure systems

(or deep depression systems) that have affected Sri Lanka over the past seven decades clearly shows that the vast majority have approached the island from the east, north‑east, and south‑east. As illustrated in the figure above, a Doppler radar installed in Pottuvil would therefore provide significantly more effective monitoring of upper‑atmospheric behaviour over the south‑eastern and eastern maritime regions than a radar located in Puttalam.

Under the original JICA‑supported project, two state‑of‑the‑art Doppler radar systems were to be installed, ensuring full coverage of Sri Lanka’s landmass and surrounding maritime zones. By 2018, the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission (TRC) had granted the necessary frequency allocations, and most other institutional approvals had been secured by 2017.

In this context, it is important to determine whether delays in implementing the project stemmed from decisions taken by senior officials within the Department of Meteorology or from broader institutional or administrative constraints. The suspension of nearly all Japanese‑funded projects in Sri Lanka after 2019 also contributed significantly to the postponement of this initiative.

In this context, it is important to determine whether delays in implementing the project stemmed from decisions taken by senior officials within the Department of Meteorology or from broader institutional or administrative constraints. The suspension of nearly all Japanese‑funded projects in Sri Lanka after 2019 also contributed significantly to the postponement of this initiative.

With the recent resumption of previously suspended Japanese projects, the Doppler radar initiative has been revived. However, due to global cost escalations, the project now provides for only one radar system instead of the originally planned two. In my professional assessment, if only a single Doppler radar can be installed, Pottuvil is the more appropriate and strategically valuable location, mainly for tracking cyclones or low-pressure areas. Given the country’s current disaster‑risk landscape, re‑engaging with JICA to explore the feasibility of installing the second radar in Pottuvil would be of immense benefit to the Department of Meteorology

Additional key recommendations

1. Transition to satellite‑based communication systems

Adopt satellite‑based communication platforms (e.g., Starlink) for data transmission from the Department of Meteorology’s Automatic Weather Stations (AWS) and Automatic Rain Gauges, replacing vulnerable ground‑based infrastructure.

2. Strengthen public trust in weather forecasts

Enhance credibility by adopting globally recognised Impact‑Based Forecasting, which not only states expected weather conditions (e.g., 100 mm of rainfall) but also explains their likely impacts on people, infrastructure, and livelihoods. This user‑centric approach increases public attention and trust.

3. Modernise monitoring networks across technical agencies

Extend satellite‑based communication systems to the Department of Irrigation and NBRO for transmitting data from automatic rain gauges, water‑level sensors, and flow‑measurement devices.

4. Upgrade emergency communication for the DMC

Equip the Disaster Management Centre with satellite‑based communication systems to ensure uninterrupted coordination during emergencies. Initial engagement with Starlink is a promising step.

5. Standardise emergency broadcasting

During declared disaster emergencies, require all television and radio broadcasters to simultaneously transmit official announcements. This prevents misinformation and ensures the public receives clear, unified instructions. Alerts should also be disseminated via SMS, and internationally recognised systems such as the Common Alerting Protocol (CAP) should be adopted.

6. Enforce disaster‑resilient construction standards

All reconstruction must comply strictly with the Sri Lanka Building Code and relevant standards. Preparatory work for these codes, initiated with World Bank support, should be accelerated. Many highly experienced Sri Lankan and expatriate engineers have offered their expertise voluntarily and excessive institutional bureaucracy must not impede their contribution.

7.Regulate reconstruction in high‑risk zones

Introduce new regulations requiring that rebuilding in mountainous regions and areas adjacent to reservoirs strictly follow NBRO recommendations.

8. Reactivate Disaster Committees

Reinstate the Disaster Committees mandated under the Disaster Management Act and amend any provisions requiring strengthening or modernisation.

9. Strengthen technical capacity

Recruit qualified personnel for key technical institutions and provide them with appropriate local and overseas training. Engage final‑year university students in technical support roles to build future capacity.

10.Enhance international cooperation

Expand international partnerships on disaster management and establish personnel‑exchange mechanisms for major emergencies.

11.Assess and secure vulnerable hospitals

Identify hospitals at risk from natural hazards and either relocate them or eliminate the sources of risk.

12. Establish resilient public facilities

Construct permanent public buildings in disaster‑prone areas or upgrade existing facilities, and provide structured, practical disaster‑response training to nearby communities under DMC coordination.

13.Raise public awareness

Strengthen disaster‑risk education, particularly among schoolchildren, to build long‑term community resilience.

14.Promote household emergency preparedness

Encourage families to maintain a small “Emergency Disaster Kit” containing essential items such as water, dry food, medicines, first‑aid supplies, important documents, national identity cards, and a battery‑operated radio.

15.Conduct seasonal preparedness programs

Before monsoon seasons, implement public awareness campaigns and practical drills in high‑risk areas on basic safety measures and first aid during floods, landslides, and lightning events.

Conclusion

In the aftermath of a major disaster, it is imperative that authorities adopt sustainable, scientifically sound, and long‑term solutions before rebuilding the country. At the same time, every citizen has a responsibility to contribute, swiftly, constructively, and with a shared sense of national purpose, to the recovery and resilience of Sri Lanka.

(The author is a Chartered Electrical Engineer and a member of the Institution of Engineering and Technology (UK), with postgraduate qualifications in Electronics Engineering and Satellite Communication. He has led a World Bank–funded, ADPC-administered project on climate-resilient urban and peri-urban farming in Sri Lanka. A freelance consultant in lightning protection, he serves as a Technical Advisory Member at the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Modern Technologies, is an Executive Committee Member of the South Asian Lightning Network (SALNET), and has chaired national standards committees on lightning protection. He can be contacted on (WhatsApp): +94773373586)