Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 15 September 2025 01:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Every day spent maintaining outdated systems is a day stolen from the future our students deserve

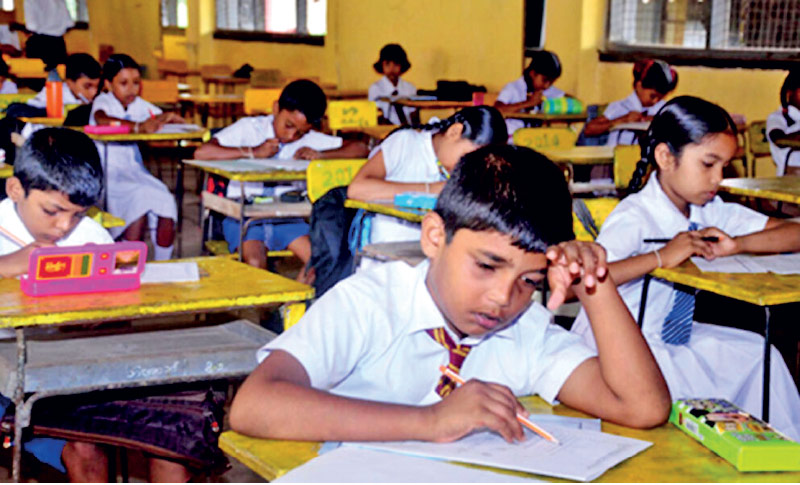

Sri Lanka’s education system remains dominated by the A/L and O/L examination culture, where success is narrowly defined by grades rather than holistic development. This has created a teaching-to-the-test mentality that stifles creativity, critical thinking, and practical application of knowledge. Students spend years memorising content for high-stakes examinations while developing little understanding of how their learning applies to real-world challenges

Sri Lanka’s education system remains dominated by the A/L and O/L examination culture, where success is narrowly defined by grades rather than holistic development. This has created a teaching-to-the-test mentality that stifles creativity, critical thinking, and practical application of knowledge. Students spend years memorising content for high-stakes examinations while developing little understanding of how their learning applies to real-world challenges

“If we want a different country, we must first imagine a different classroom”

“If we want a different country, we must first imagine a different classroom”

Bold new framework confronts policy makers and academics with uncomfortable truths about educational failure and demands immediate transformation

Bold new framework confronts policy makers and academics with uncomfortable truths about educational failure and demands immediate transformation

Sri Lanka’s educational establishment faces its most direct challenge yet with the release of “The ‘why’ of education: A framework for transformation”—a provocative blueprint that questions fundamental assumptions about learning and demands that policy makers and academics answer a critical question: Are we preparing students for our past, or for their future?

Sri Lanka’s educational establishment faces its most direct challenge yet with the release of “The ‘why’ of education: A framework for transformation”—a provocative blueprint that questions fundamental assumptions about learning and demands that policy makers and academics answer a critical question: Are we preparing students for our past, or for their future?

The framework pulls no punches in its assessment of current educational priorities, asking stakeholders to confront an uncomfortable reality: while other nations have transformed their educational systems to meet 21st-century challenges, Sri Lanka remains trapped in colonial-era thinking that prioritises conformity over creativity, memorisation over meaning, and grades over genuine growth.

“When we teach our students today, the way we were taught yesterday, we are stealing their tomorrow.” This stark warning encapsulates the moral crisis facing Sri Lankan education—every day spent maintaining outdated systems is a day stolen from the future our students deserve.

The economic implications of this theft are staggering, and the numbers tell a devastating story of squandered potential against a ticking demographic clock:

The demographic countdown: By 2037, Sri Lanka’s elderly population (60+) is projected to double, reaching 5.2 million, up from 2.5 million in 2012. By 2042, nearly 1 in 4 Sri Lankans will be elderly—making Sri Lanka one of the fastest-aging countries in South Asia. This demographic shift is happening before the country reaches high-income status—a phenomenon described as “growing old before becoming rich.” The country has a narrow window to maximise its youth potential before the dependency ratio reverses and economic strain intensifies.

The youth crisis: Meanwhile, the youth unemployment rate (ages 20–29) in Sri Lanka stands at a staggering 17%, with 21.6% unemployment among those aged 20–24. Among those with A/L qualifications and above, unemployment is 8% overall, and 10.2% for women. A 2024 study found that critical thinking and problem-solving skills among secondary school students are significantly underdeveloped, with low scores in analytical decision-making and creative reasoning. Graduates—especially in the humanities—face chronic underemployment, often working in roles far below their qualifications and earning potential.

The brutal reality: The system produces degrees, not capabilities. The mismatch between education and market needs is widening precisely when Sri Lanka can least afford to waste its human capital.

This creates a catastrophic scenario: as Sri Lanka’s demographic dividend narrows and the working-age population begins to decline, the country may find itself in the humiliating position of importing talent from neighbouring countries—India, Bangladesh, and the Philippines—to fill positions that should have been occupied by well-educated Sri Lankan youth. The irony is devastating: while Sri Lankan graduates struggle with unemployment or underemployment despite their degrees, multinational companies and growing economies in the region actively recruit the kind of innovative, adaptable, and ethically-grounded professionals that Sri Lanka’s educational system has failed to produce.

The framework warns that continuing with educational mediocrity will force Sri Lanka into a dependency cycle where the nation exports its brightest minds to countries with better opportunities while importing foreign talent to fill critical positions at home. With less than 15 years before the demographic shift fundamentally alters Sri Lanka’s economic landscape, this brain drain coupled with talent import represents not just an economic failure, but a generational betrayal—where an entire cohort of young Sri Lankans are denied the education they need to lead their country’s recovery, while foreign professionals fill the leadership vacuum that local talent should have occupied.

The uncomfortable questions policy makers must answer

The framework challenges Sri Lankan educational leaders with pointed questions that demand honest answers:

“We do not educate to fill minds—we educate to form souls,” the framework declares, directly challenging the fundamental premise of current educational policy. This is not merely a philosophical difference—it’s an indictment of a system that has prioritised measurable outputs over meaningful outcomes.

Four pillars that expose current educational failures

Formation over information: Moving beyond knowledge transfer to shape character, cultivate discernment, and awaken purpose in students. This pillar fundamentally redefines educational success—instead of measuring how much information students can memorise and regurgitate, it focuses on developing ethical reasoning, empathy, and moral courage. In practical terms, this means incorporating character education into every subject, teaching students to grapple with ethical dilemmas, and fostering environments where values like integrity, compassion, and responsibility are not just taught but lived. Students learn to ask not just “What do I know?” but “Who am I becoming?” This approach recognises that true education shapes the whole person, preparing students to make principled decisions when faced with real-world challenges.

Education as usefulness: Preparing students to be “not just employable, but indispensable—to their community, their conscience, and their calling.” This pillar transforms the traditional focus from individual achievement to collective contribution. Rather than creating graduates who simply fill existing positions, this approach develops individuals who can identify societal needs and create innovative solutions. Students engage in project-based learning tied to real-world problems, participate in community service initiatives, and develop entrepreneurial thinking that serves the greater good. They graduate not as passive job-seekers but as active problem-solvers who understand their responsibility to their nation’s development. This reframes success from personal advancement to societal impact, from competition to collaboration, fostering graduates who see their education as a tool for national transformation.

Education as legacy: Recognising that “every classroom is a rehearsal for the future” and that today’s teaching becomes tomorrow’s culture. This pillar acknowledges education’s profound intergenerational impact—the values, habits, and mindsets cultivated in today’s classrooms will shape Sri Lanka’s leadership, communities, and culture for decades to come. Schools must therefore intentionally create rituals, traditions, and practices that reinforce positive values and forward-thinking approaches. This means establishing mentorship programs where older students guide younger ones, creating school cultures that celebrate character alongside achievement, and developing educational practices that students will carry into their future roles as parents, leaders, and citizens. Every educational decision is made with the question: “What kind of society will this create in 20 years?”

Education as liberation: Empowering students with agency and hope, particularly crucial in post-crisis Sri Lanka’s recovery. This pillar is especially vital for a nation rebuilding from economic and social challenges. Education must free students from limiting beliefs about their potential, from passive acceptance of problems they could solve, and from the notion that meaningful change is impossible. Through debate, inquiry, and civic engagement activities, students develop the confidence to question existing systems, the skills to propose solutions, and the courage to lead transformation. This approach cultivates citizens who see themselves as agents of positive change rather than victims of circumstance. In post-crisis Sri Lanka, this means developing a generation that approaches national challenges with optimism, creativity, and determination—young people who believe in their power to rebuild and reimagine their country’s future.

A stark choice for educational leaders

The framework presents academics and policy makers with an ultimatum disguised as an opportunity. While other nations have embraced educational transformation, Sri Lanka’s leaders face a critical decision point that will determine whether the country produces another generation of followers or finally develops the leaders it desperately needs.

The time for incremental change has passed. The framework demands that educational leaders choose between:

The systemic failures we can no longer ignore

The framework forces policy makers to confront the devastating consequences of educational complacency:

What this framework demands from academics

University professors, educational researchers, and curriculum designers can no longer remain comfortable in their ivory towers while the nation’s educational system fails its students. The framework challenges academics to:

Stop theorising and start implementing: Move beyond publishing papers about educational reform to actively piloting and scaling proven innovations in real classrooms with measurable impact.

Abandon intellectual protectionism: Break down artificial barriers between disciplines and embrace the interdisciplinary, problem-based learning that develops students capable of addressing complex societal challenges.

Take responsibility for teacher preparation: Acknowledge that current teacher training programs are producing educators ill-equipped for 21st-century learning and completely redesign preparation programs around mentorship, character development, and experiential pedagogy.

The moral imperative for policy makers

For government officials, ministry leaders, and education directors, the framework presents a moral reckoning: every day that passes without fundamental educational transformation is another day that Sri Lankan students are denied the preparation they need to rebuild their nation.

Stop hiding behind bureaucratic processes: The research is clear, the global models are proven, and the local need is urgent. Policy makers must move from committee discussions to bold action.

Accept accountability for educational outcomes: When graduates lack ethical reasoning, when youth unemployment remains high, when civic engagement declines, these are not inevitable outcomes—they are the direct result of policy choices that prioritise political convenience over student development.

Stop the funding hypocrisy: In 2023, Sri Lanka allocated just 1.83% of its GDP to education—less than half the global average of 4.4%. This places Sri Lanka as the third-lowest country in the world for education spending, behind only Haiti and Laos. While policy makers speak of education as a “national priority,” the budget reveals the truth: Sri Lanka spends less on preparing its future leaders than some of the world’s most struggling economies. Historically, the country’s education spending peaked at 3.34% in 1996 but plummeted to a shameful 1.2% in 2022. How can leaders claim to value education while systematically defunding it?

The teacher development catastrophe: Even more damning is the complete neglect of teacher development within this already inadequate budget. While there’s no standalone figure for teacher development as a percentage of GDP, available reports suggest it’s subsumed within the broader education budget—which is already underfunded. According to UNICEF’s 2021 Budget Brief, teacher training and professional development receive minimal allocation, often treated as a discretionary expense rather than a strategic investment. This underinvestment is especially alarming given that 86.8% of primary school teachers are technically “trained,” but many lack exposure to modern pedagogies, coaching methods, and digital fluency. Teacher autonomy and mentorship culture—hallmarks of high-performing systems like Finland and Singapore—remain underdeveloped in Sri Lanka.

The content delivery trap: Sri Lanka has created a generation of teachers who can deliver content but cannot develop character. They can recite curricula but cannot inspire creativity. They can maintain classroom discipline but cannot mentor personal transformation. These educators enter classrooms equipped with subject knowledge but lacking the tools to shape souls, build critical thinking, or develop ethical reasoning—precisely the capabilities Sri Lanka’s future leaders desperately need.

The accountability misdirection: This is not a teacher problem—it’s a policy failure. When teachers struggle to engage students, when graduates lack practical skills, when educational outcomes disappoint, policy makers consistently blame educators rather than examining their own systematic neglect of teacher development. Teachers cannot give what they have never received. They cannot model what they have never been taught. The failure lies not in the classroom but in the ministries and institutions that treat the most important profession for national development as an afterthought in budget planning and strategic thinking.

Invest in transformation, not maintenance: Continuing to underfund a broken system while hoping for different results is not just poor policy—it’s a betrayal of every student who deserves better and every taxpayer who expects their government to prioritise the nation’s future over short-term political gains.

The cost of educational cowardice

The framework warns that educational leaders who choose comfort over transformation will bear responsibility for:

The final challenge: Prove you’re different

“If we don’t know why we educate, how can we know what to teach or how to lead?” This question stands as a direct challenge to every educational leader in Sri Lanka.

The framework concludes with a stark ultimatum: “If we want a different Sri Lanka, we must first imagine a different classroom.” This is not a suggestion—it’s a demand. Educational leaders must prove they are capable of the vision, courage, and commitment necessary to transform not just schools, but the entire trajectory of the nation.

The evidence is clear, the models are proven, and the need is urgent. The only question that remains is whether Sri Lanka’s educational leaders will rise to meet this moment or be remembered as the generation that had the opportunity to transform their nation’s future but chose instead to maintain comfortable mediocrity.

The choice is theirs. The consequences will be ours.