Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 26 November 2025 00:22 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka’s most valuable resource is its people. Some will contribute to the economy, either by building enterprises or by working for them. Others will be too young to work. Yet others will be considered to have completed their work life.

It is important to understand how many are in what categories and what changes over time mean for the economy and society. Investments may not be made if the right kinds of people are not available. Taxes will have to be increased if the state has to take care of more of the elderly. Health expenditures may be out of control.

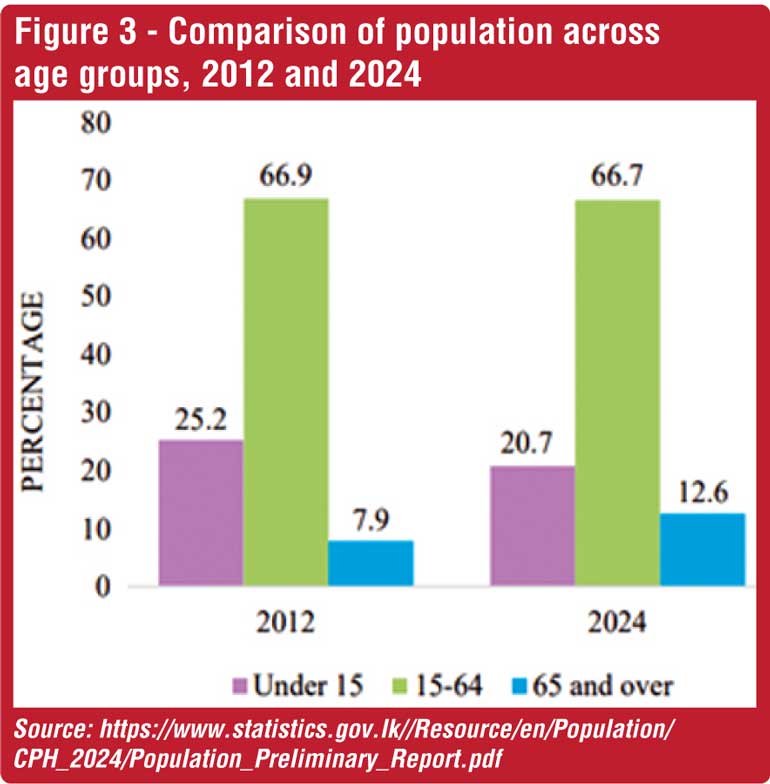

The concept of a demographic dividend, wherein the working-age population has to deal with low elder dependency and low child dependency directly or indirectly, is now widely accepted. An example of direct is the expenditures incurred by parents in providing care for pre-school children while they work. Indirect is where taxes have to be paid to fund elder care and the additional demands made on the public healthcare system.

Low elder and child dependencies are seen as having contributed to the rise of the Asian Tiger economies (Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan), more than the industrial policies dear to many Sri Lankan decision makers. If the youthful energies associated with the dividend are blocked from productive activity, insurrections will arise. Sri Lanka has run through its main demographic dividend period from the 1970s with little to show other than deaths and damage from three insurrections.

Recent demographic trends

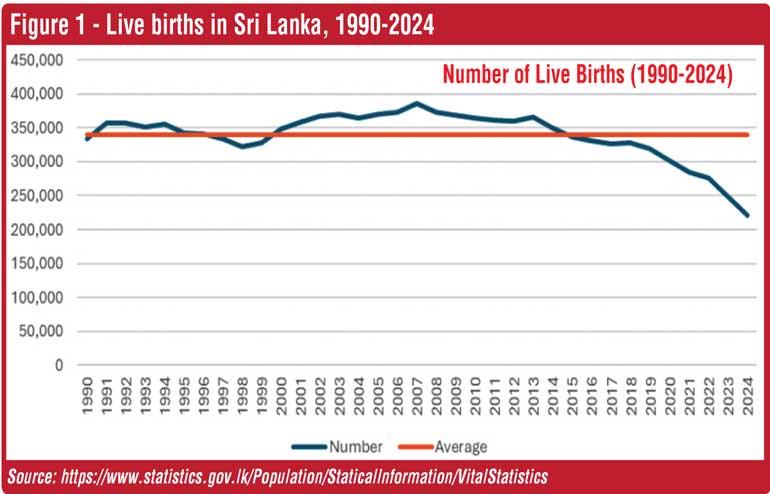

Between the years of 2000 and 2014, Sri Lanka experienced an unusual and not yet fully explained increase in births. After 2014, the decline in fertility resumed and accelerated and is now likely to advance when Sri Lanka reaches peak population.

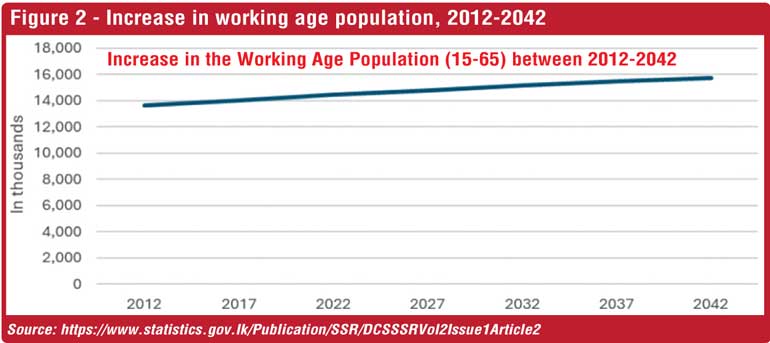

The increased number of children led to greater demand for year-one admissions, which is now sharply declining. It is increasing the numbers entering the workforce at the present time. This will taper off from around 2032.

The workforce will remain constant or even show a slight increase, until the decline kicks in. The immediate challenge is finding productive opportunities for the young people joining the workforce. Then, the challenge will become one of increasing productivity so the economy can be sustained by less workers.

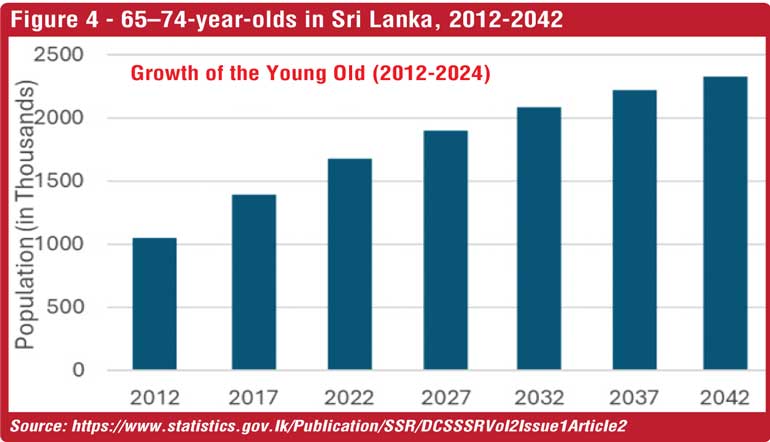

However, elder dependency has already started to increase and will accelerate because more people will live longer. The costs to families and society caused by elder dependency are considerable.

The population above 65 is conventionally divided into young-old (65-74 years); middle-old (75-84) and oldest-old (over 85 years). In Sri Lanka, age 60 is used as the marker of old age.

What does all this mean?

For a long, planners have worried about how to deal with the young. Lacking enough opportunities and release valves, they are likely to wreck the kinds of devastation visited upon Kathmandu and Dhaka. It may not be a coincidence that the 2022 Aragalaya coincided with the first of those born during the mini population boom of 2000-2014 reaching working age. This group will keep coming into the workforce until 2034-36. It would be foolish of those in power not to act decisively to expand economic opportunities for them as the highest priority, especially because the escape valve of migration is being gradually shut.

Governments have been fiddling with the retirement age of state employees without a coherent plan. For example, the retirement age was raised, and then lowered in 2022 as part of the crisis response resulting in a large number of retirements that year. Expenditure on salaries and wages of public servants decreased by 4%. But for the same reason, expenditure on pensions increased by 6.3%. In the case of salaries, the state gets something in return. It gets no service in return for pension payments from competent, experienced persons who are forced to twiddle their thumbs at home.

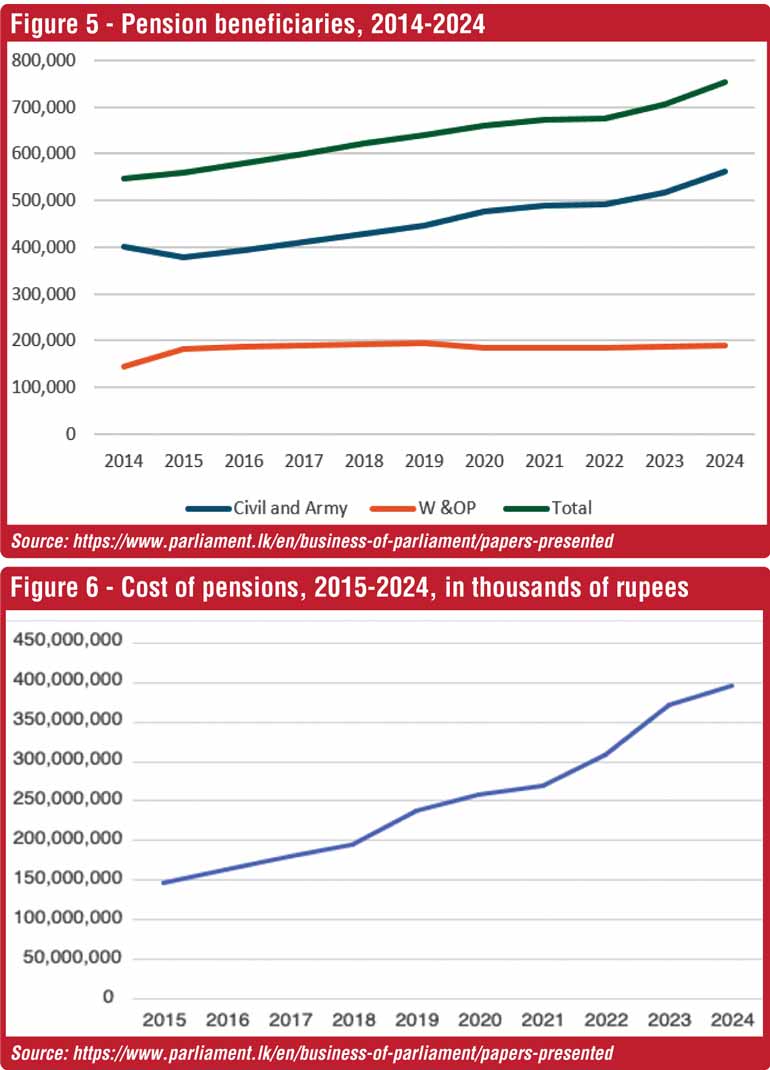

The current retirement age of 60 is unsustainable because of increasing longevity and because the current pension scheme is non-contributory (funded year by year, using taxes paid in future years). The Widows, Widowers and Orphans Fund is contributory, a model for reform. The fiscal deficit cannot be reduced by paying pensions to retirees for 30-40 years. Currently, pensions and gratuity eat up 6% of total Government expenditures and will keep increasing.

While the larger problem is that of establishing a comprehensive social safety net for all the elderly, urgent action is needed to stop the unfunded pension obligation from squeezing out other essential expenditures. Not only are the beneficiaries increasing, the costs are multiplying. What cost Rs. 150 billion in 2014, now costs Rs. 400 billion, a 2.66x increase.

It seemed from the NPP’s 2021 Rapid Response Plan that they were somewhat sensitive to the looming threat of elder dependency. But the first year in power appears to have replaced such concerns with more mundane matters. Unless those in power and those seeking power start now, we will all become victims of the demographic time bomb.