Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Tuesday, 6 January 2026 00:51 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Cyclone Ditwah has imposed a severe humanitarian and economic shock on Sri Lanka. With World Bank estimates placing direct physical damage at around US$4.1 billion (around 4% of GDP), the need for rapid public action is undeniable. Emergency shelter, rehabilitation of agriculture, and the repair of damaged infrastructure require fiscal space and foreign exchange at a moment when Sri Lanka’s macroeconomic position remains extremely fragile.

Cyclone Ditwah has imposed a severe humanitarian and economic shock on Sri Lanka. With World Bank estimates placing direct physical damage at around US$4.1 billion (around 4% of GDP), the need for rapid public action is undeniable. Emergency shelter, rehabilitation of agriculture, and the repair of damaged infrastructure require fiscal space and foreign exchange at a moment when Sri Lanka’s macroeconomic position remains extremely fragile.

It is within this context that Verité Research Executive Director Dr. Nishan De Mel, has argued against reliance on the IMF’s Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI), proposing instead a mix of alternative foreign-currency borrowing – particularly from the diaspora and potentially through new international sovereign bond (ISB) issuances – alongside a relaxation of domestic fiscal constraints.

While Dr. De Mel is correct to emphasise the scale of the financing challenge posed by Ditwah, his proposals risk pushing Sri Lanka further down a path that has already proven destabilising: the deepening commercialisation of both its foreign and domestic public debt. This path will only increase the country’s dependency on, and vulnerability to, the whims of financial markets.

Misreading risk and interest rates

A central pillar of Dr. De Mel’s argument is that IMF RFI financing is “costly” when one accounts for surcharges, exchange rate movements, and effective interest rates in local currency terms. From this, he concludes that alternative borrowing – particularly from the Sri Lankan diaspora or via domestic USD instruments – would be cheaper.

This comparison, however, rests on a flawed benchmark. It implicitly assumes that the Sri Lankan Government could borrow from the diaspora at interest rates comparable to those earned on USD deposits held in domestic commercial banks. This assumption collapses once risk is properly considered. Lending to the sovereign, especially a sovereign that has recently defaulted and undergone a contentious restructuring, is fundamentally different from holding deposits in regulated banks with their own balance sheets and protections.

The relevant interest rate for any new Government USD borrowing is not the deposit rate paid to diaspora savers, but the yield Sri Lanka would need to offer on ISBs. Even in the absence of currently quoted ISB rates, there is little doubt that such yields would embed a substantial risk premium – likely exceeding the effective cost of IMF RFI financing. To suggest otherwise is to underestimate how markets price sovereign risk in post-default contexts.

In this sense, Dr. De Mel’s cost calculations obscure rather than clarify the real trade-offs facing policymakers.

From emergency finance to commercial debt dependence

More troubling than the arithmetic is the structural direction of Dr. De Mel’s proposals. Whether framed as diaspora borrowing, domestic USD bonds, or ESG-linked international issuances underwritten by multilaterals, the underlying mechanism is the same: additional commercial or quasi-commercial foreign-currency debt.

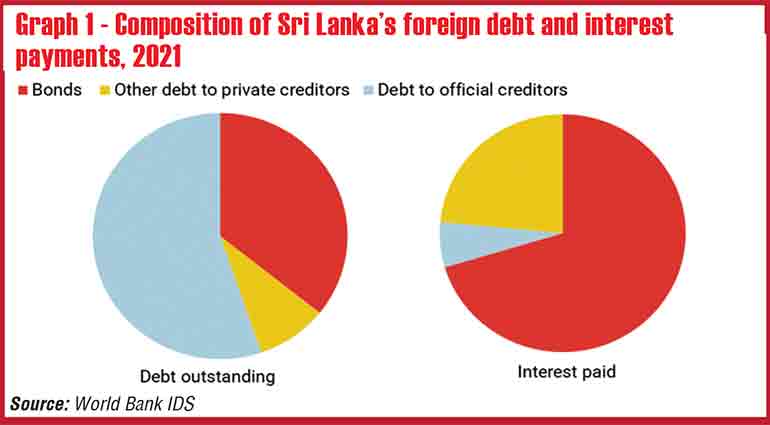

This is not a neutral choice. Sri Lanka’s recent crisis was precipitated precisely by an overreliance on market-based external borrowing. As the graph 1 shows, Sri Lanka’s shift toward commercial foreign debt, and in particular ISBs, has increased its foreign debt-servicing costs. What needs adding is that the shift towards international commercial debt has made Sri Lanka more vulnerable to external shocks such as Ditwah. This is because unlike official creditors, private bondholders neither roll over debt countercyclically nor provide emergency liquidity in crisis moments. As such, liquidity stress resulting from an external shock rapidly transforms into a solvency crisis. Seen in this light, proposals to finance post-Ditwah reconstruction through diaspora bonds, domestic USD instruments, or new ISB-type issuances risk deepening Sri Lanka’s external debt problems. While such instruments may differ in branding or investor base, they operate through the same commercial logic reflected in the graph. They add to foreign-currency liabilities that must be serviced at market-determined rates and under conditions of heightened uncertainty. Expanding commercial external borrowing in response to a climate disaster would deepen, rather than alleviate, the very vulnerabilities that precipitated Sri Lanka’s default.

Sri Lanka’s recent crisis was precipitated precisely by an overreliance on market-based external borrowing

Moreover, the debt restructuring that followed Sri Lanka’s default – one that Dr. De Mel himself supported – has left the country with limited fiscal and monetary sovereignty and heightened sensitivity to new commercial obligations.

In this light, the distinction between borrowing from the diaspora and borrowing from international investors is largely immaterial. Both add to foreign-currency liabilities that must be serviced under conditions of uncertainty, and both reinforce a development strategy anchored in financial markets rather than productive investment.

Emergency IMF financing is not without cost, nor should it be accepted uncritically. But replacing it with new forms of commercial or market-based debt – whether branded as diaspora solidarity or ESG innovation – does not resolve Sri Lanka’s vulnerability

Conspicuously absent from Dr. De Mel’s analysis is any serious engagement with alternatives that would reduce, rather than repackage, external debt burdens – most notably a moratorium on, or suspension of, foreign debt repayments in the aftermath of a climate disaster (such as that proposed by a group of 121 experts). Such measures, while politically contentious, would directly address the worsening foreign reserve constraint without further entrenching commercial debt obligations.

A genuinely cautious approach would prioritise debt relief, temporary moratoria, and non-debt-creating financing wherever possible, while recognising climate disasters as exogenous shocks demanding international responsibility

Fiscal flexibility without financing clarity

Dr. De Mel also calls for relaxing expenditure limits imposed by the Public Finance Management framework, arguing that extraordinary circumstances justify higher Government spending. In principle, this is a defensible position: disaster response cannot be mechanically bound by peacetime fiscal rules.

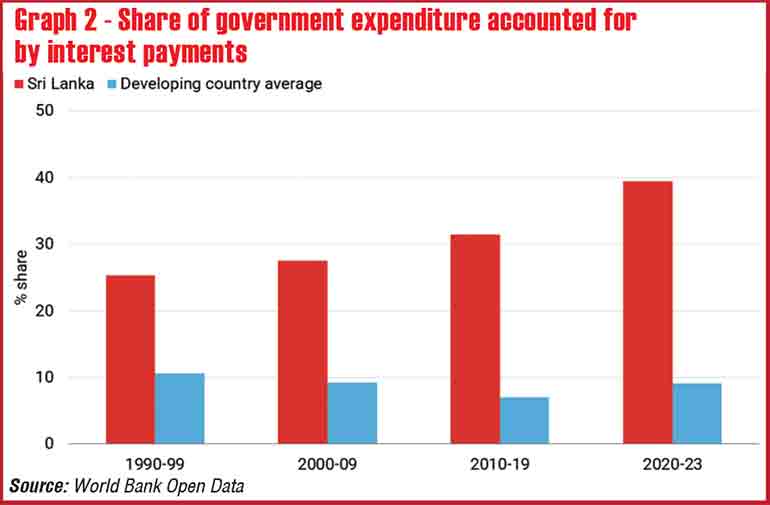

Yet here again, the proposal stops short of confronting its implications. For one thing, there is little justification offered for the magnitude of the additional spending envisaged (apart from accepting IMF estimates). More importantly, there is no clear account of how the increased expenditure will be financed. By remaining silent on monetary and financial constraints – particularly those imposed by the new Central Bank Act – the argument implicitly accepts that expanded deficit financing will come from domestic commercial sources, compounding the Government’s already comparatively heavy local currency debt burden (see graph 2) and keeping real interest rates at high levels. Without access to concessional finance or debt relief, greater fiscal flexibility will simply lock disaster-related spending into permanently higher debt-servicing burdens, leaving Sri Lanka exposed both to volatile global markets and a costly, market-driven debt trap at home.

The debt restructuring that followed Sri Lanka’s default – one that Dr. De Mel himself supported – has left the country with limited fiscal and monetary sovereignty and heightened sensitivity to new commercial obligations

A cautionary conclusion

Sri Lanka’s response to Cyclone Ditwah must balance urgency with prudence. Dr. Nishan De Mel is right to warn against knee-jerk policymaking, but his own recommendations risk reproducing the very dynamics that led Sri Lanka into crisis: reliance on commercial borrowing, exposure to volatile capital markets, and the normalisation of debt-led adjustment.

Emergency IMF financing is not without cost, nor should it be accepted uncritically. But replacing it with new forms of commercial or market-based debt – whether branded as diaspora solidarity or ESG innovation – does not resolve Sri Lanka’s vulnerability.

A genuinely cautious approach would prioritise debt relief, temporary moratoria, and non-debt-creating financing wherever possible, while recognising climate disasters as exogenous shocks demanding international responsibility. Without such a reorientation, the aftermath of Ditwah may mark not a break from the past, but another step down the road of debt commercialisation that Sri Lanka can ill afford.

(Howard Nicholas is a retired associate professor in economics, Institute of Social Studies (The Netherlands). Shiran Illanperuma is a researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. Bram Nicholas is the COO of the research and training company ETIS Lanka.)