Sunday Mar 01, 2026

Sunday Mar 01, 2026

Thursday, 4 April 2024 00:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Introduction

Introduction

The IMF’s explanation of Sri Lanka’s recent foreign exchange crisis is fiscal and monetary mismanagement; fiscal excesses funded by Central Bank printing. The solution proposed by the IMF is to reduce the budget deficit (‘fiscal consolidation’) and prevent the Central Bank from printing money to finance it. Particular emphasis is placed on the attainment of a primary budget surplus – Government revenue minus expenditure less interest and amortisation payments, and particular emphasis in respect of the attainment of this primary surplus is placed on increasing taxes. The Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) is quoted by the IMF (2023) as committing itself to,

“…an ambitious primarily revenue-based fiscal adjustment while protecting the vulnerable. Our program will achieve a central government primary surplus of 2.3 percent of GDP by 2025 and in subsequent years.”

We argue that not only is the IMF’s diagnosis of the source of Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange problem mistaken (see Nicholas and Nicholas, 2023), the proposed remedy (i.e., an increase in tax revenue) ignores one of the major sources of the budget deficit; the excessively high levels of interest payments on both domestic and foreign debt. It is the excessively high interest payments alongside excessively low tax revenue that account for Sri Lanka’s excessively high overall budget deficit. We further argue that the IMF’s focus on the primary budget balance allows the problem of high interest payments to be ignored – with potentially damaging consequences.

The primary deficit

Although the IMF argues that the solution to Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange crisis is a contraction of the GOSL’s overall budget deficit, their focus in the first instance is on the primary balance. They suggest that in the first instance the GOSL should attempt to reduce the primary deficit and eventually run a primary surplus. The rationale for doing so, they typically argue, is that it signals to investors and credit rating agencies that the Government is committed to maintaining sound finances.

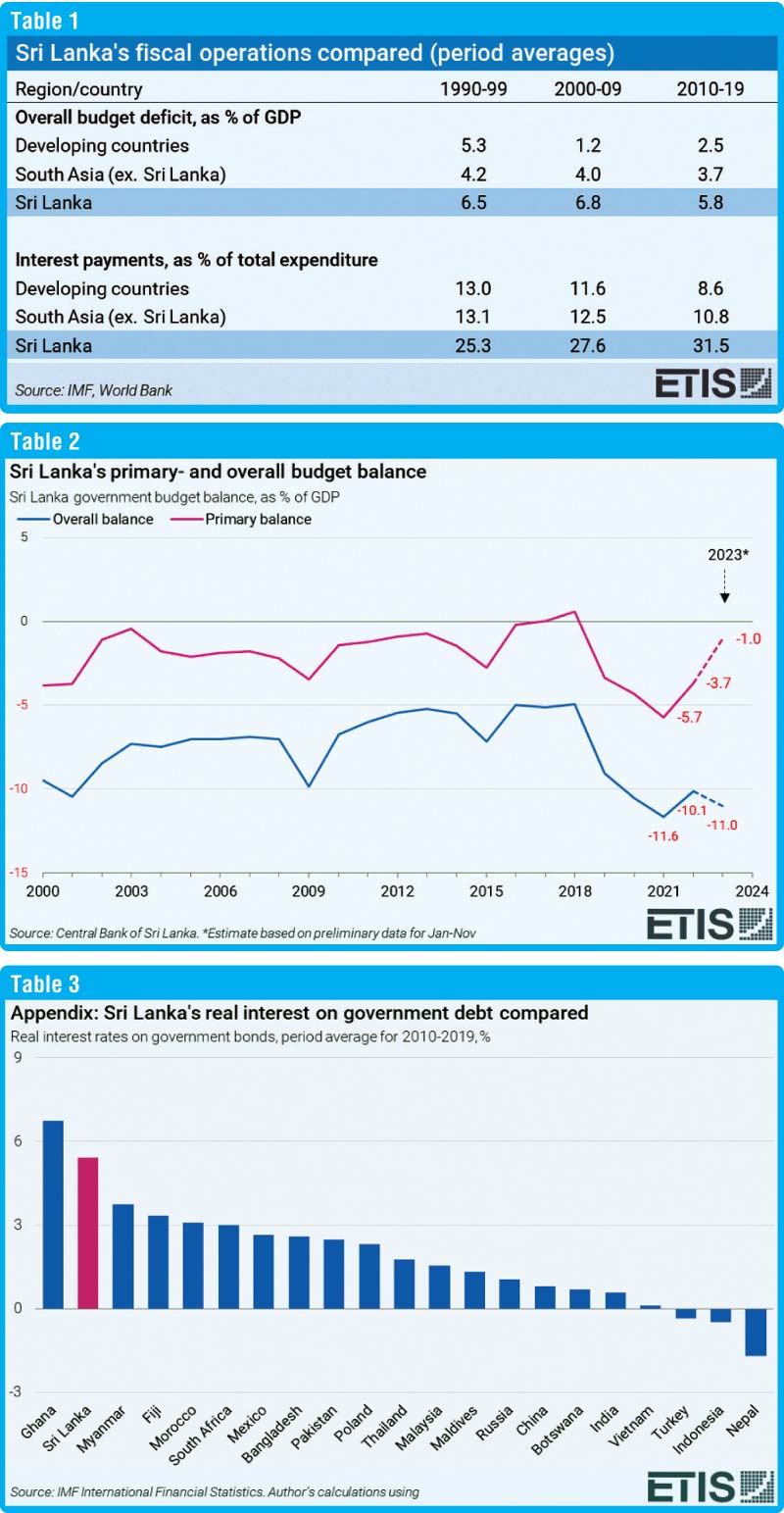

Table 1 provides an indication of the excessiveness of both the GOSL’s budget deficit and interest payments on its debt. It shows that the budget deficit as a percentage of GDP and interest payments as a percentage of total expenditure have been relatively higher than those of other developing countries over a very long period of time. Of particular note is that unlike other developing countries, including other South Asian countries, trend interest payments of the GOSL as a percentage of total expenditure have continued to rise over the period 1990-2019 as a whole. That is to say, although there can be little doubt that something needed to be done about the relatively low level of tax revenue (Sri Lanka having one of the lowest tax revenue bases among developing countries), there can also be little doubt that something needed to be done about the excessively high level of interest payments on Government debt (see Appendix).

The consequence of focusing on the primary budget deficit

The consequence of the IMF’s focus on the primary balance is that it causes, or rather allows, policy makers to ignore the role of excessively high interest payments as one of the most important, if not the most important, source of the protracted rise in the government’s budget deficit. Hence, as Table 2 shows, even though the GOSL has managed to reduce the primary budget deficit, the overall deficit has worsened due to high interest payments. It must surely be a cause for concern to investors in Sri Lankan Government debt and rating agencies that in spite of an increase in Government revenue amounting to 2% of GDP there has been an increase in the overall budget deficit and a worsening of the overall debt situation of the Government. The latter must raise questions about the ability of the Government to service its debt, particular since the recently promulgated Central Bank Act (CBA) prohibits the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) from buying Government debt except in ‘emergencies’.

The IMF is most certainly aware of the pressure interest payments by the GOSL have exerted on the fiscal balance. In its 2023 report on the Sri Lankan economy the IMF (2023, p. 11) argues that, “These large fiscal deficits reflected substantially low tax revenues and high debt service costs” (our emphasis).

In spite of this, the IMF insists on the GOSL focusing in the first instance on the primary deficit without paying any heed to the high level of debt service costs. Indeed, even though current projections suggest the GOSL is likely to miss its target budget deficit of 7.9% for 2023 as a whole, the IMF seems satisfied with its fiscal progress in respect of the reduction of the primary budget deficit. The reason for the IMF’s deliberate neglect of the high debt service costs and corresponding overall budget deficit could be their concern that drawing attention to the former would require the adoption of policies that it is vehemently opposed to. Firstly, it could lead to an amendment of the CBA that allows the CBSL to directly or indirectly purchase government debt in other than emergency situations.

Secondly, it could lead to a greater use of ‘captive sources’ (such as the Bank of Ceylon and the People’s Bank) for financing of the budget where these sources are informally used to ‘front-run’ (set the prices of Government debt) in Government debt markets – something the IMF has been long opposed to.

Thirdly, it could also lead to a reduced reliance on external commercial debt to finance the budget, which we showed in a previous article to be problematic not just in terms of its strain on Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange reserves, but also due to it being even more expensive than the government’s local currency debt (see Nicholas and Nicholas, 2023). Rather, the IMF appears to be pinning its hopes on the current exceptionally high debt service burden imposing fiscal discipline on the GOSL, and the latter, together with a battery of liberalisation measures, resulting in higher economic growth and a corresponding increase in tax revenues resulting in a lowering of this burden. On the basis of the past experiences of Sri Lanka and other developing countries entering into adjustment agreements with the IMF, this happy scenario is unlikely to materialise. Instead, the likely outcome is a continuation of Sri Lanka’s excessive debt burden, the prevalence of relatively higher interest rates, continued downward pressure on non-interest social expenditure by Government, and a further drift towards a low growth rentier economy that is subject to periodic foreign and domestic debt crises. As we have argued in Nicholas and Nicholas (2023) the possibility of a foreign debt crisis is ever present in all economies that fail to go down the export-oriented industrialisation path. This is because these economies experience continuous current account deficits that require them to borrow in foreign capital markets to meet their foreign exchange requirements, resulting inevitably in foreign debt problems.

The possibility of a domestic debt crisis arises from the difficulty that the GOSL will face in significantly reducing the size of the budget deficit in the context of weak economic growth, the prohibition of the CBSL from either directly or indirectly purchasing Government debt except in emergencies, and the reluctance of commercial banks to purchase increasingly risky Government debt.

References:

IMF (2023) Sri Lanka Country Report. No 23/116. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Nicholas, H. and Nicholas, B. (2023) ‘An Alternative View of Sri Lanka’s Debt Crisis’, Development and Change 0(0): 1–22. DOI: 10.1111/dech.12794.

(Bram Nicholas is the COO of the research and training company ETIS Lanka. Howard Nicholas is a retired associate professor in economics, Institute of Social Studies (The Netherlands).)