Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Friday, 5 December 2025 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

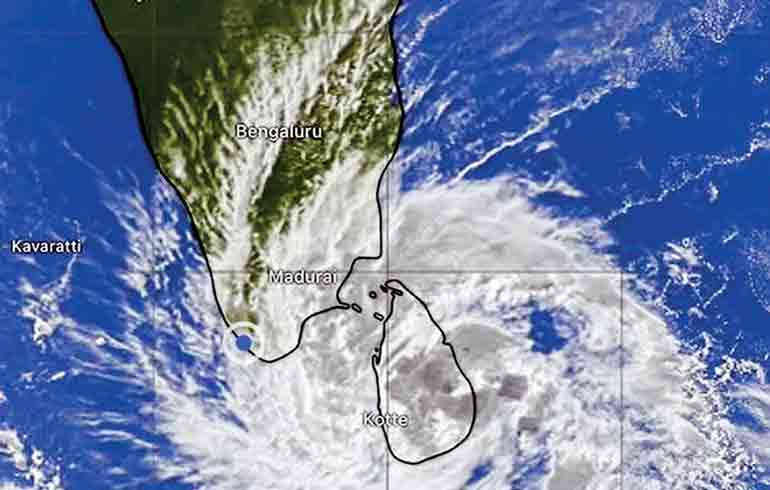

The waters may have started to recede, but the scars remain. Cyclone Ditwah has left Sri Lanka facing one of its worst flooding and landslide disasters in two decades with all 25 districts battered, villages buried, families displaced, and livelihoods erased. The official death toll hovers around 390, yet the true figure is likely to be far higher, with entire communities swallowed by landslides and mud.

The waters may have started to recede, but the scars remain. Cyclone Ditwah has left Sri Lanka facing one of its worst flooding and landslide disasters in two decades with all 25 districts battered, villages buried, families displaced, and livelihoods erased. The official death toll hovers around 390, yet the true figure is likely to be far higher, with entire communities swallowed by landslides and mud.

International donors have pledged support, but even here the limitations are stark. India, China, the United States, Australia, Japan, have all committed humanitarian grants. Yet these grants will arrive in kind, not in cash — food, medicine, tents, and equipment — and only if donors are satisfied that the goods reach the affected communities without infiltration or diversion. This reflects a deep mistrust of Sri Lanka’s relief channels, where past experiences of leakage and politicisation have eroded confidence. This mistrust is not unfoundedEven technical protocols were disregarded. Engineers of the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) confirm that when rainfall exceeding 200 mm is predicted in reservoir catchment areas, the regulation is to open the gates in advance to prevent overflow and downstream flooding. Yet during Ditwah, gates remained closed until it was too late. The result was catastrophic as reservoirs spilled suddenly, amplifying floods and sweeping away homes to compound the destruction.Prof. Galagedera’s hydrological analysis underscores the scale of this failure. Sri Lanka absorbed 10% of its annual rainfall in just 24 hours. With soils already saturated, every drop became surface runoff. His calculations show 150,000 cubic meters per second of water blasting through a country only 0.93% the size of the Amazon basin — yet producing 70% of the Amazon River’s peak discharge. That is not weather; that is a hydrological red alert. And Sri Lanka’s infrastructure was never designed for what is coming.Worse still, reports suggest that the Disaster Management Centre itself had been made dormant, stripped of capacity and left ineffective. Villagers in the hills cried out that no officials had arrived, no relief had reached them, and no one came to see if they were alive or dead. This is not just deafness to warnings but the deliberate silencing of the very institution meant to protect citizens.The tragedy is not only in the repetition of disaster, but in the repetition of negligence. Sri Lanka’s leaders remain deaf to science and blind to history, choosing optics over preparedness. This is a call for consciousness and accountability: to break the cycle of denial, to listen when warnings are sounded, and to act before lives and livelihoods are lost. Cyclone Ditwah is therefore not just a storm; it is a verdict.The tradeoff (lives vs livelihoods)Cyclone Ditwah was not only a humanitarian disaster but also an economic shockwave. What is confirmed is that Cyclone Ditwah caused massive economic losses across agriculture, fisheries, tourism, banking, and insurance, with overall damages estimated between Rs. 210 to 320 billion, equal to nearly 1% of Sri Lanka’s GDP (Daily Mirror, 2 Dec. 2025).CAL Research estimates that more than 15,000 homes were destroyed, over 200 roads and 10 bridges damaged, and vast swathes of farmland were washed away. The losses ripple across every sector: rice, maize, vegetables, tea plantations, tourism, insurance, and banking. Farmers have seen their livelihoods obliterated. Inland fishing and prawn farming, according to early commentary, may have suffered losses running into tens of billions of rupees, though official assessments are still consolidating. Small businesses, already weakened by years of economic crisis, were swept away overnight. Tourism operators report cancellations across the island, while banks brace for defaults from borrowers whose collateral now lies under water.The blow to tourism is particularly severe. By mid-November, arrivals were already below the 2025 target of 2.5 million. With Cyclone Ditwah’s devastation, that target is now a castle in the air. Tourism receipts projected at $ 2.5 billion will fall short, undermining one of Sri Lanka’s most vital foreign currency lifelines.At the same time, garment exports, Sri Lanka’s largest foreign exchange earner, face new tariffs from the Trump administration. Sri Lanka Exports to United States was $ 2.88 billion during 2024. ( Sri Lanka Exports to United States - 2025 Data 2026 Forecast 1990-2024 Historical).This compounds the crisis. Garments and tourism together represent the backbone of Sri Lanka’s dollar inflows. Their disruption means the projected foreign currency earnings will not materialise, leaving reserves under strain.The currency markets are already reacting. In the past two months, the Sri Lankan rupee has depreciated against the US dollar, and with reduced inflows from garments and tourism, the Central Bank will have fewer reserves to defend the currency. Cyclone Ditwah therefore threatens not only homes and farms, but the stability of the LKR itself.The tradeoff, lives versus livelihoods, is brutal. Families displaced in shelters face not only the trauma of loss but the collapse of their economic future. Relief payments may cover funerals and temporary food, but they do not rebuild prawn ponds, replant tea estates, or reopen shops.This is the hidden cost of negligence. By ignoring warnings and failing to prepare, the state has forced its citizens to pay twice, first with their lives, then with their livelihoods. The billions now spent on compensation and rebuilding could have been invested in prevention with drainage systems, flood routing models, and resilient infrastructure. Instead, Sri Lanka remains trapped in a cycle of destruction and repair, sympathy and debt.Cyclone Ditwah has revealed the fragility of an economy that cannot withstand shocks. It is a reminder that disaster management is not only about saving lives in the moment, but about safeguarding livelihoods and stabilising the currency for the future. Without sciencedriven prevention, every storm becomes an economic crisis, and every flood a setback to national recovery.Relief (mis)managementIf consequence management was neglected, relief management was mishandled. Survivors across districts complained that food, medicine, and shelter were slow to arrive, unevenly distributed, or diverted before reaching those most in need. Villagers in the hills reported that “no one has come yet… no relief has reached us”, a chilling echo of abandonment in the midst of disaster.International donors have pledged support, but even here the limitations are stark. India, China, The United States, Australia, Japan, have all committed humanitarian grants. Yet these grants will arrive in kind, not in cash — food, medicine, tents, and equipment — and only if donors are satisfied that the goods reach the affected communities without infiltration or diversion. This reflects a deep mistrust of Sri Lanka’s relief channels, where past experiences of leakage and politicisation have eroded confidence.This mistrust is not unfounded. After the 2004 tsunami, Sri Lanka received unprecedented global goodwill and financial aid. Yet the infamous “Helping Hambantota” scandal revealed how funds were siphoned into private accounts linked to then Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, under the guise of rebuilding Hambantota.(Helping Hambantota investigation « LANKA Standard) Investigations by the Auditor General and CID exposed misappropriation of tsunami aid, and the case became a symbol of how disaster relief was infiltrated and diverted for political ends. (Transparency and accountability in disaster relief: A new era after decades of misuse | Daily FT)

Farmers have seen their livelihoods obliterated. Inland fishing and prawn farming, according to early commentary, may have suffered losses running into tens of billions of rupees, though official assessments are still consolidating. Small businesses, already weakened by years of economic crisis, were swept away overnight. Tourism operators report cancellations across the island, while banks brace for defaults from borrowers whose collateral now lies under water.The blow to tourism is particularly severe. By mid-November, arrivals were already below the 2025 target of 2.5 million. With Cyclone Ditwah’s devastation, that target is now a castle in the air. Tourism receipts projected at $ 2.5 billion will fall short, undermining one of Sri Lanka’s most vital foreign currency lifelines.At the same time, garment exports, Sri Lanka’s largest foreign exchange earner, face new tariffs from the Trump administration. Sri Lanka Exports to United States was $ 2.88 billion during 2024. ( Sri Lanka Exports to United States - 2025 Data 2026 Forecast 1990-2024 Historical).This compounds the crisis. Garments and tourism together represent the backbone of Sri Lanka’s dollar inflows. Their disruption means the projected foreign currency earnings will not materialise, leaving reserves under strain.The currency markets are already reacting. In the past two months, the Sri Lankan rupee has depreciated against the US dollar, and with reduced inflows from garments and tourism, the Central Bank will have fewer reserves to defend the currency. Cyclone Ditwah therefore threatens not only homes and farms, but the stability of the LKR itself.The tradeoff, lives versus livelihoods, is brutal. Families displaced in shelters face not only the trauma of loss but the collapse of their economic future. Relief payments may cover funerals and temporary food, but they do not rebuild prawn ponds, replant tea estates, or reopen shops.This is the hidden cost of negligence. By ignoring warnings and failing to prepare, the state has forced its citizens to pay twice, first with their lives, then with their livelihoods. The billions now spent on compensation and rebuilding could have been invested in prevention with drainage systems, flood routing models, and resilient infrastructure. Instead, Sri Lanka remains trapped in a cycle of destruction and repair, sympathy and debt.Cyclone Ditwah has revealed the fragility of an economy that cannot withstand shocks. It is a reminder that disaster management is not only about saving lives in the moment, but about safeguarding livelihoods and stabilising the currency for the future. Without sciencedriven prevention, every storm becomes an economic crisis, and every flood a setback to national recovery.Relief (mis)managementIf consequence management was neglected, relief management was mishandled. Survivors across districts complained that food, medicine, and shelter were slow to arrive, unevenly distributed, or diverted before reaching those most in need. Villagers in the hills reported that “no one has come yet… no relief has reached us”, a chilling echo of abandonment in the midst of disaster.International donors have pledged support, but even here the limitations are stark. India, China, The United States, Australia, Japan, have all committed humanitarian grants. Yet these grants will arrive in kind, not in cash — food, medicine, tents, and equipment — and only if donors are satisfied that the goods reach the affected communities without infiltration or diversion. This reflects a deep mistrust of Sri Lanka’s relief channels, where past experiences of leakage and politicisation have eroded confidence.This mistrust is not unfounded. After the 2004 tsunami, Sri Lanka received unprecedented global goodwill and financial aid. Yet the infamous “Helping Hambantota” scandal revealed how funds were siphoned into private accounts linked to then Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, under the guise of rebuilding Hambantota.(Helping Hambantota investigation « LANKA Standard) Investigations by the Auditor General and CID exposed misappropriation of tsunami aid, and the case became a symbol of how disaster relief was infiltrated and diverted for political ends. (Transparency and accountability in disaster relief: A new era after decades of misuse | Daily FT) The echoes are unmistakable. Cyclone Ditwah has once again exposed a system where relief risks being politicised, misused, or delayed. Donors now insist on strict oversight, refusing to release cash unless accountability is guaranteed. Citizens, meanwhile, are left waiting for supplies that may or may not arrive, while memories of past scandals deepen their distrust.The result is a double blow, survivors abandoned in the present, and a nation haunted by the ghosts of past relief scandals. Relief becomes a patchwork of supplies rather than a coordinated lifeline. Families displaced into shelters face not only the trauma of loss but the indignity of waiting for aid that history suggests may be misused.This is not simply a logistical failure but a moral one. Inadequate relief distribution compounds the tragedy, turning survivors into supplicants and exposing the fragility of Sri Lanka’s disaster governance.Institutional failure and reformCyclone Ditwah has laid bare the collapse of Sri Lanka’s disaster governance. Institutions meant to protect citizens such as the Disaster Management Centre, the Ceylon Electricity Board, and local councils, were either dormant, reactive, or absent. Relief was mismanaged, consequence planning ignored, and warnings dismissed. What emerges is not just a failure of logistics, but a failure of competence.The contrast with Chennai, India could not be sharper. When faced with torrential rains in late November, Chennai’s authorities:Closed schools in advance to protect children.Deployed rescue boats and emergency teams before waters rose.Issued red alerts early, ensuring citizens were warned and prepared.Mobilised humanitarian commitment by opening shelters, distributing food and deploying medical teams.The result was stark. Despite heavy rainfall and widespread waterlogging, Chennai recorded only three deaths. Sri Lanka, by contrast, ignored categorical cyclone warnings, cancelled exams only after the disaster struck, and left hospitals under water. Hundreds of lives were lost and billions in livelihoods were destroyed.This is the difference between state competence and state negligence. Chennai demonstrated responsiveness, preparedness, and humanitarian commitment. Sri Lanka demonstrated deafness, blindness, and paralysis.Reform is therefore not optional but existential. Sri Lanka must:

The echoes are unmistakable. Cyclone Ditwah has once again exposed a system where relief risks being politicised, misused, or delayed. Donors now insist on strict oversight, refusing to release cash unless accountability is guaranteed. Citizens, meanwhile, are left waiting for supplies that may or may not arrive, while memories of past scandals deepen their distrust.The result is a double blow, survivors abandoned in the present, and a nation haunted by the ghosts of past relief scandals. Relief becomes a patchwork of supplies rather than a coordinated lifeline. Families displaced into shelters face not only the trauma of loss but the indignity of waiting for aid that history suggests may be misused.This is not simply a logistical failure but a moral one. Inadequate relief distribution compounds the tragedy, turning survivors into supplicants and exposing the fragility of Sri Lanka’s disaster governance.Institutional failure and reformCyclone Ditwah has laid bare the collapse of Sri Lanka’s disaster governance. Institutions meant to protect citizens such as the Disaster Management Centre, the Ceylon Electricity Board, and local councils, were either dormant, reactive, or absent. Relief was mismanaged, consequence planning ignored, and warnings dismissed. What emerges is not just a failure of logistics, but a failure of competence.The contrast with Chennai, India could not be sharper. When faced with torrential rains in late November, Chennai’s authorities:Closed schools in advance to protect children.Deployed rescue boats and emergency teams before waters rose.Issued red alerts early, ensuring citizens were warned and prepared.Mobilised humanitarian commitment by opening shelters, distributing food and deploying medical teams.The result was stark. Despite heavy rainfall and widespread waterlogging, Chennai recorded only three deaths. Sri Lanka, by contrast, ignored categorical cyclone warnings, cancelled exams only after the disaster struck, and left hospitals under water. Hundreds of lives were lost and billions in livelihoods were destroyed.This is the difference between state competence and state negligence. Chennai demonstrated responsiveness, preparedness, and humanitarian commitment. Sri Lanka demonstrated deafness, blindness, and paralysis.Reform is therefore not optional but existential. Sri Lanka must:

- Rebuild the Disaster Management Centre with autonomy, resources, and authority.

- Invest in realtime rainfall radars and flood routing models, so warnings translate into action.

- Automate spill gate protocols at reservoirs, ensuring engineers act on science, not politics.

- Enforce landuse rules to prevent settlements in highrisk zones.

- Establish transparent relief channels to rebuild donor trust and ensure aid reaches survivors.

- Integrate consequence management with epidemic prevention, water safety, and health system resilience into disaster planning.

Prof. Galagedera’s hydrological red alert is a reminder that Sri Lanka’s infrastructure was never designed for what is coming. Climate change will bring more Ditwahs, not fewer. Without reform, every storm will be a verdict on state failure.Sri Lanka must choose whether to remain trapped in cycles of negligence, or build institutions that embody competence, responsiveness, and humanitarian commitment. The lesson from Chennai is clear - preparedness saves lives, competence builds trust, and responsiveness turns disaster into resilience.The call to consciousnessCyclone Ditwah is not just a storm but a verdict. It has judged the institutions that ignored warnings, the leaders who appointed committees instead of building systems, and the culture that confuses sympathy with responsibility.Sri Lanka has been here before. After the tsunami, relief was infiltrated and diverted. After every flood, epidemics followed. After every disaster, another committee was appointed. Yet no investment was made in preparedness - no radars, no flood routing, no spill gate automation, no consequence planning. The cycle repeats with destruction, sympathy, rebuilding and debt.Now, even as Ditwah’s waters recede, rumors swirl of another system forming near Sumatra. Whether or not it strikes Sri Lanka, the point is clear and the country remains exposed. A nation that manages only outcomes — funerals, relief supplies, rebuilding committees — but never consequences, will always be blindsided by the next storm.The call now is to consciousness. To break the cycle of sympathy and debt, Sri Lanka must embrace accountability, competence, and science‑driven preparedness. Every storm is a test. Ditwah was failed. The next one will come, whether in two weeks or two years. The question is whether Sri Lanka will still be appointing committees or finally building institutions that can withstand the windThe lesson is not about weather but about governance. Competence is not a luxury. Preparedness is not optional. Humanitarian commitment is not charity, it is duty. Chennai showed what responsiveness looks like with schools closed in advance, boats deployed, alerts issued and lives saved. Sri Lanka showed what negligence looks like with warnings ignored, hospitals under water and relief politicized.Cyclone Ditwah must therefore be remembered not only for its destruction, but for its revelation. It revealed a state that cannot protect its citizens, an economy that cannot withstand shocks, and a health system that collapses under pressure. Most of all, it revealed the cost of blindness — the refusal to see beyond the nose, to anticipate consequences, to invest in resilience.The call now is to consciousness. To break the cycle of sympathy and debt, Sri Lanka must embrace accountability, competence, and sciencedriven preparedness. Every storm is a test. Ditwah was failed. The next one will come, whether in two weeks or two years. The question is whether Sri Lanka will still be appointing committees or finally building institutions that can withstand the wind.(The author has built a distinguished career in banking and education, both in Sri Lanka and overseas. He has lectured widely, trained senior executives, and designed workshops that blend policy insight with practical tools. Renowned for his expertise in strategy formulation and company turnarounds, Bradley has guided institutions through complex challenges, repositioning them for growth and resilience. His dual background in finance and education, enriched by global exposure, makes him a compelling voice on reform, transformation, and nation branding.)Recent columns

COMMENTS