Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday, 9 September 2025 00:53 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

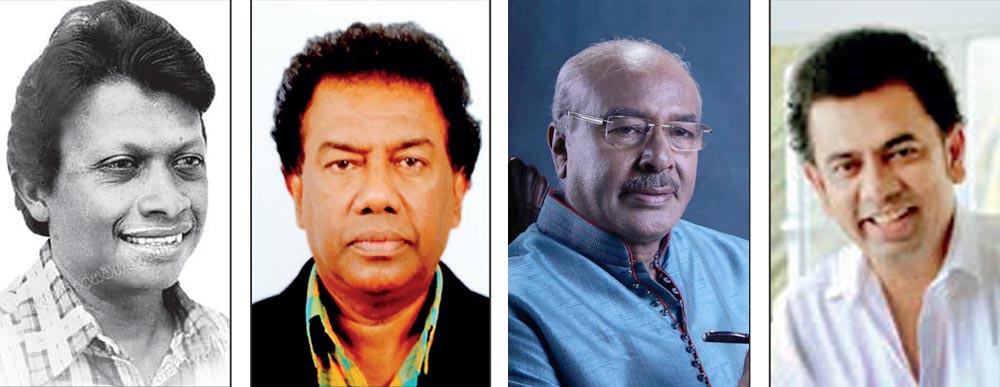

Premakeerthi De Alwis, Nawarathna Gamage, Dr. Rohan Weerasinghe, Amila Thenuwara

Sri Lanka exists within the global community, not apart from it. Yet, in public discourse surrounding law, technology, governance, and culture, a recurring theme persists: the belief that Sri Lanka is somehow exceptional, requiring uniquely local solutions. While national context is important, this mindset often overlooks a critical reality: we operate within an interconnected world governed by international norms. Nowhere is this more evident than in the realm of copyright law, particularly in music.

Sri Lanka exists within the global community, not apart from it. Yet, in public discourse surrounding law, technology, governance, and culture, a recurring theme persists: the belief that Sri Lanka is somehow exceptional, requiring uniquely local solutions. While national context is important, this mindset often overlooks a critical reality: we operate within an interconnected world governed by international norms. Nowhere is this more evident than in the realm of copyright law, particularly in music.

Legal status of copyright law in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s legal framework for copyright is principally established under the Copyright Act No. 36 of 2003. This legislation defines the extent of copyright protection, and the rights granted to creators. It is designed to be consistent with international norms, ensuring Sri Lanka’s adherence to global copyright treaties and conventions. The Act offers broad protection for a variety of creative works, including literary, musical, artistic, and software-related content, thereby covering a diverse range of intellectual property.

The copyright conundrum in Sri Lanka

As both an engineer and a lyricist, I have navigated the complexities of Sri Lankan copyright firsthand. Collaborating with fellow artists has revealed a widespread misunderstanding of copyright law, its local application and its international framework. Too often, debates are shaped by personal grievances and anecdotal outcomes rather than a clear grasp of legal principles. The public adores singers who entertain them immensely. Singers use this to their advantage to build a legally indefensible demand in front of law and policy makers using public as shield. In social media, various artists started spreading their interpretation of copyright law and the gullible public, who have no knowledge of copyright law or global standards, and who only experience the product, which is the song delivered by the singer, started believing the interpretations are true.

The danger here is that politicians generally go the extra mile to please the majority public without realising the adverse impacts on internationally acceptable legal status. The law maker should know that Sri Lanka has been a signatory to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works since 1959. This treaty, administered by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), sets global standards for copyright protection, ensuring creators retain rights over their original works across borders.

Economic and moral rights

Creators are entitled to two key protections: Economic rights: The ability to reproduce, distribute, sell, rent, or translate their work. Moral rights: The right to claim authorship and preserve the integrity of the work.

In Sri Lanka, these rights extend for the creator’s lifetime plus 70 years, mirroring global standards. If the creation is a joint effort by various parties under an agreement, until the last person in the party dies and after 70 years from that date, the copyrights remain active.

The anatomy of a song

A song is rarely the product of a single individual. It typically involves: the lyricist who crafts the words, the composer who creates the melody, singer who performs the song, the recording engineer who captures the performance, mixing technician who refines the sound and videographer who adds visual story telling.

By law, the song belongs to the lyricist except the music composition which belongs to the composer. Hence, basically the song in entirety belongs to both lyricist and the music composer. This division of ownership is not unique to Sri Lanka, it’s a global norm rooted in respect for individual creative contributions. The process is deeply personal.

Some lyricists, like the late Premakeerthi De Alwis, produced iconic lyrics in minutes. Others take months. The value lies not in time spent, but in the depth of creativity and experience. Consider the story of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, who once struggled with a physics problem at Princeton. Yasantha Rajakarunanayake, a student from Sri Lanka, solved the problem within minutes by verbally providing the answer, not through brute-force calculation, but by employing intuitive mathematical reasoning. He later elaborated on his approach in a detailed two-page written explanation. This anecdote underscores the value of accumulated knowledge, a trait shared by artists and scientists alike.

Collaboration and transformation

Once lyrics are handed to a composer, the creative journey continues. Musicians reconfigure lines, fill silences with nuance, and weave layers of sound.

Song lyrics differ fundamentally from poetry. While both are creative expressions, lyrics are crafted with an inherent rhythm unique to the lyricist’s vision. When these lyrics are handed over to a musician, they undergo a transformative process as the musician works to compose a melody that complements or sometimes reimagines that rhythm.

Each musician approaches this task differently. For instance, the esteemed veteran composer Nawarathna Gamage often draws inspiration from thousands of existing songs, using them as a foundation to improvise and develop original tunes. In contrast, Dr. Rohan Weerasinghe widely recognised as one of the most exceptional talents in Sri Lanka’s contemporary music scene employs a distinctive creative methodology that incorporates a broad array of musical instruments. Personally, I find that his compositions echo certain stylistic elements reminiscent of the legendary Indian maestros Rahul Dev Burman (Pancham) and Sachin Dev Burman, both of whom remain my all-time favourites. One day, I may cross paths with him, and when I do, I look forward to discovering his unique creative process.

From my experience working with four different Sri Lankan musicians, I have observed varied approaches to melody creation. Some take several days to develop a tune, and the final composition may diverge significantly from the rhythm originally envisioned by the lyricist. This iterative process often involves modifying the lyrics to better align with the evolving melody, culminating in a finalised musical arrangement.

However, the lyricist’s role does not end there. Revisions to the lyrics frequently continue up until the final stages of production, ensuring that the words and music are in perfect harmony.

The highly talented lyricist, Amila Thenuwara’s last-minute addition to “Ikigasa Handana” helped the song win national acclaim. Similarly, the best musician Sri Lanka had, Dr. Premasiri Khemadasa’s transformation of “Landune” originally a simple poem by Ranbanda Seneviratne into a timeless classic, launched Amarasiri Peiris into stardom.

Musicians also shape the music arrangement using carefully selected instruments and intensity. Their role is both technical and artistic, ensuring the highest production quality.

Reimagining lyrics and the role of the singer

Much like architecture, music is a collaborative endeavour. The lyricist conceptualises the emotional and poetic framework, the musician designs the sonic structure, and the singer brings the composition to life. In this analogy, the singer akin to the builder who just build the structure as per architectural and structural designs, is tasked with executing the vision without altering its core. The singer must adhere to the melody crafted by the composer and the lyrics written by the lyricist. Any deviation requires mutual consent from both creators.

While singers infuse songs with emotion, soul, and technical finesse, they do not hold copyright ownership of the composition. This distinction raises important questions about the sustainability of a singer’s career. The answer lies in performance rights, a legal mechanism that allows singers to earn from their performances, provided there is agreement with the lyricist and composer on the commercial use of the song and sharing of earnings or benefits that come from the song’s performance. Of course, singer is essential to generate revenue from the song, but it does not mean the singer owns the song. This area remains underdeveloped in Sri Lanka. As artists engage globally, aligning domestic law with international standards is imperative. Clearer definitions and protections will foster a more equitable creative industry.

Investment and contracts in the music industry

For instance, a lyricist may compose a song and engage a musician, vocalist, and recording engineer to bring it to life. While the musician may be compensated for their contribution, the musical composition itself remains their intellectual property. In such cases, any revenue the lyricist earns from the commercial use of the song after recouping initial production costs should be shared equitably with the musician.

Likewise, if the musician commercially exploits the song with the lyricist’s consent, the resulting income should be fairly divided between both parties. In these scenarios, the singer is not directly involved in the ownership or revenue-sharing unless they hold copyright.

However, if a singer who does not own rights to the song performs it in a commercial context, any income generated should be distributed fairly among the lyricist, musician, and singer, acknowledging each party’s creative contribution.

Navigating Sri Lanka’s unregulated music industry

As someone who has ventured into music production several times and someone who abandoned a few projects due to financial constraints, I have come to realise that Sri Lanka’s music industry operates with little structure and even less transparency. It is, in many ways, a chaotic marketplace where pricing appears arbitrary and inconsistent.

Based on my personal experience, the cost of hiring vocalists varies wildly. Established singers typically charge between Rs. 250,000 and Rs. 600,000 per song. Meanwhile, younger artists, many of whom are recent products of reality television, demand anywhere from Rs. 100,000 to Rs. 380,000. What’s perplexing is the lack of any clear criteria for these fees. For instance, I encountered a young artist with just three years in the industry quoting Rs. 380,000, while one of Sri Lanka’s top five vocalists, with hundreds of songs to their name, asked for only Rs. 250,000. I’ve heard that fees are increasing at an unsustainable rate, which is marginalising talented lyricists with limited financial resources. This pattern previously led to the decline of quality in the film industry, and there is a real concern that the music industry may face a similar fate.

Musicians responsible for producing complete tracks including mixing and mastering charge between Rs. 70,000 and Rs. 400,000. In this segment, pricing tends to reflect experience and reputation more accurately, though even here, standards are far from consistent.

All of this unfolds in a country where the average monthly salary is approximately Rs. 50,000. For a talented lyricist or an independent producer, the financial barrier to creating a single song is daunting. More importantly, there are few, if any, viable avenues to recover such an investment, let alone turn a profit.

I am not advocating for Government-imposed price controls on artistic work. Creativity should never be confined by regulation. However, I do believe there is a pressing need for transparency. Artists should be encouraged or required to publicly disclose their fees, the scope of services offered, and their professional credentials. This would empower producers and lyricists to make informed decisions and allow market forces to determine fair value. Art thrives in freedom, but even freedom benefits from a little clarity.

Final remarks

A successful song can be likened to a three-legged stool, with each leg representing a key contributor: the lyricist, the musician, and the singer. For the final product to stand strong, all three must be balanced and equally robust. However, the integrity of this structure depends not only on the strength of its individual components, but also on the foundation that connects them the legal framework governing artistic work.

This legal platform serves as the base that supports and binds the creative elements. Without it, even the strongest leg cannot stand independently. In many cases, the roles of the lyricist and musician may influence or even dictate the positioning and movement of the singer within this legal context. This reflects the reality of intellectual property rights and contractual obligations, which remain consistent across global markets.

Ultimately, navigating this legal landscape is essential for all parties involved. Without a solid understanding and alignment within this framework, sustaining a career in the music industry may prove difficult, sometimes leaving few options beyond seeking an alternative profession. Sri Lankan artists often advocate for legal reforms by lobbying policymakers. The current Government, the National People’s Power (NPP), must approach such demands with caution, ensuring that any changes to domestic law are aligned with international legal standards. Any changes must align with international standards. Improvements are welcome, but they must not compromise global copyright norms. We must shed our island mentality and embrace our place in the global creative ecosystem.

(The writer is a professional Engineer working in the Australian NSW Local Government sector. He intends to share his views on various social development areas, in addition to his chosen professional discipline to inspire youth to think differently. He is contactable via [email protected].)