Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday, 19 December 2025 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Understanding landslide vulnerability

Understanding landslide vulnerability

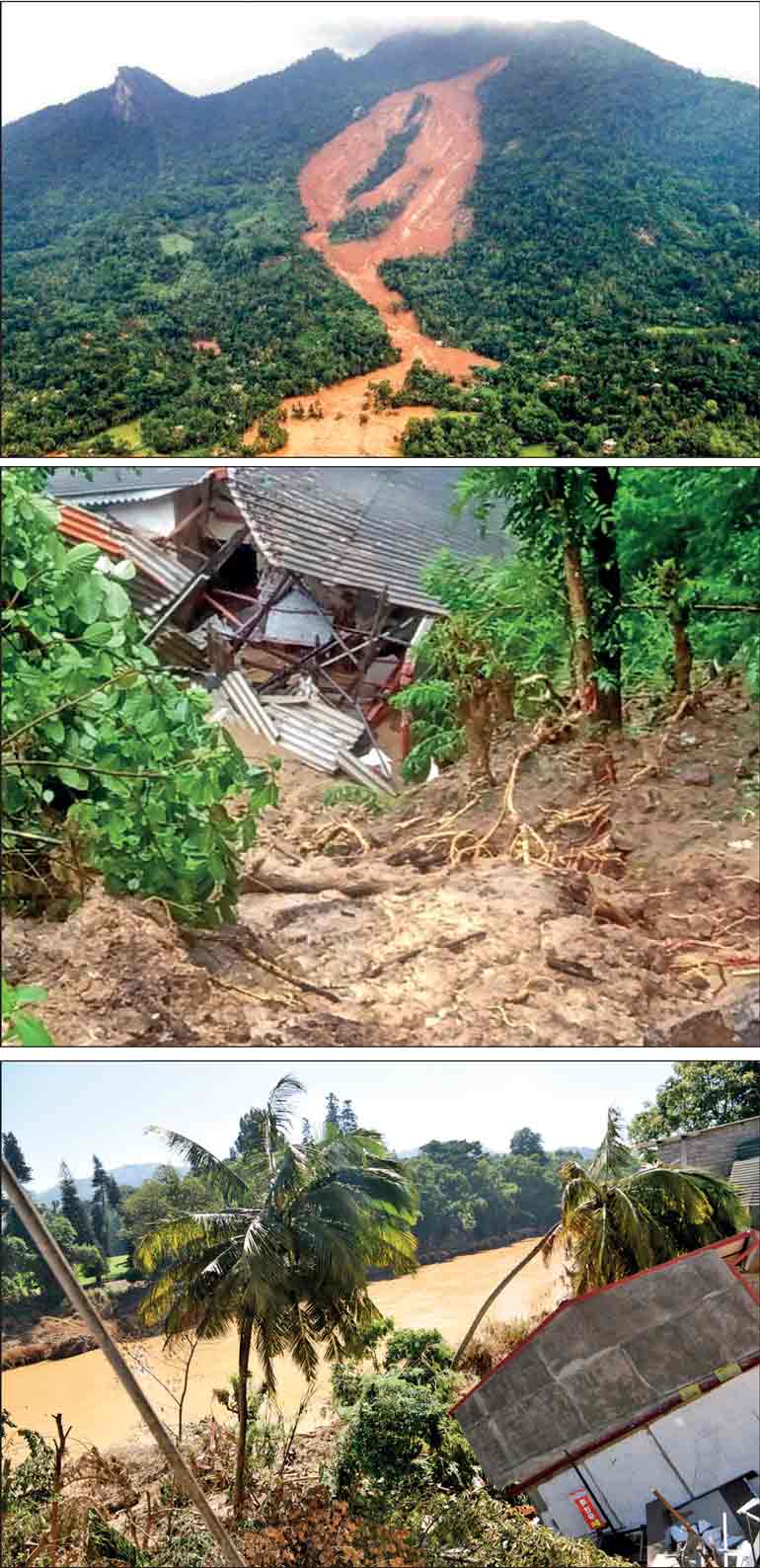

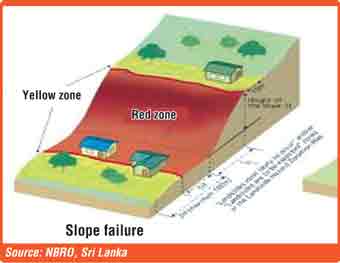

Sri Lanka was recently hit hard by Cyclone Ditwah which caused devastating floods and landslides, damaging homes, roads, and livelihoods. The Central Highlands—Nuwara Eliya, Kandy, Matale, Badulla, Kegalle, and parts of Ratnapura—are the most affected areas. Nearly 20% of Sri Lanka’s land area, predominantly within the Central Highlands, has been identified as landslide prone.

Most landslides occur in the second and third peneplains, but even isolated hillocks in the first peneplain are now increasingly vulnerable. The combined effects of steep slopes, weak soils, intense rainfall, and human activities create ideal conditions for sudden slope failures.

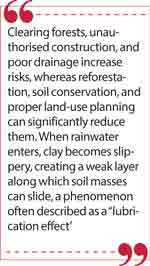

Landslide hazard zones: Yellow and red

According to the Manual for Landslide Hazard Zonation Mapping (October 2022) by the National Building Research Organisation (NBRO) in collaboration with JICA, landslide-prone areas are classified into two main zones:

Understanding these zones is essential for safe land use, construction decisions, and disaster preparedness.

How landslides occur

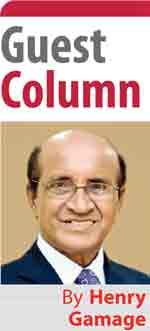

Landslides happen when water pressure within soil exceeds its strength. When this threshold is crossed, the slope loses stability almost instantly, pushing soil, rocks, trees, and even houses downhill. Failure often occurs along an underlying weak clay layer, shear zone, or sliding surface above bedrock.

The process is illustrated as follows:

Rainwater soaks the soil

Rainwater soaks the soil

↓↓↓

-----------------------------

Thick, weak, saturated soil

-----------------------------

Weak clay layer / shear zone

<- sliding surface\

>> WATER PRESSURE BUILDS >> -----------------------------

Bedrock

This mechanism explains many recent failures, including the landslides.

Why landslides happen

Landslides may occur due to natural causes, human-induced causes, or most commonly a combination of both. While natural conditions create vulnerability, human activities often trigger or worsen failures. Clearing forests, unauthorised construction, and poor drainage increase risks, whereas reforestation, soil conservation, and proper land-use planning can significantly reduce them.

In Sri Lanka’s Central Highlands, landslides result from four interacting factors, particularly during heavy rainfall:

In Sri Lanka’s Central Highlands, landslides result from four interacting factors, particularly during heavy rainfall:

1. Steep slopes

2. Geological setting and soil conditions

3. Intense and prolonged rainfall and internal water movement

4. Human-induced activities

Natural factors contributing to landslides

1. Steep slopes

The Central Highlands consist of rugged mountain terrain with slopes often exceeding 30%. Such gradients naturally favour downslope movement of soil and rock under gravity, especially when soils become saturated.

2. Geology and soil composition

The nature of rocks and soils plays a critical role. Three geological conditions particularly weaken slopes:

The Central Highlands are underlain by the Highland Complex, dominated by deeply weathered metamorphic rocks. Over time, these rocks have broken down into thick, clay-rich soils. When rainwater enters, clay becomes slippery, creating a weak layer along which soil masses can slide, a phenomenon often described as a “lubrication effect.”

Many slopes also contain colluvial deposits, a loose soil and rock material that has moved downslope and settled on steep bedrock. Though they may appear stable when dry, prolonged rainfall rapidly reduces friction along bedding planes and fractures, causing entire blocks of soil and rock to detach suddenly with great force.

Charnockite, gneiss, and schist formations are criss-crossed by foliation planes, joints, fractures, and faults, which act as conduits for water. Accumulation of water along these boundaries, especially at the soil–bedrock interface, creates high hydraulic pressure, triggering sudden slope failure.

3. Intense and prolonged rainfall

Sri Lanka’s bimodal monsoon system delivers heavy and sustained rainfall, the primary trigger for landslides. Continuous rain saturates thick soil layers, raising pore-water pressure and reducing soil strength. Areas such as Kandy, Badulla, Haldummulla, Haputale, and Kadugannawa have recorded rainfall exceeding 400 mm, causing severe damage to roads, railways, homes, and farmland.

Sri Lanka’s bimodal monsoon system delivers heavy and sustained rainfall, the primary trigger for landslides. Continuous rain saturates thick soil layers, raising pore-water pressure and reducing soil strength. Areas such as Kandy, Badulla, Haldummulla, Haputale, and Kadugannawa have recorded rainfall exceeding 400 mm, causing severe damage to roads, railways, homes, and farmland.

Climate change has intensified this risk. Low-pressure systems and cyclonic events now bring rainfall far heavier than traditional monsoons, leading to prolonged soil saturation, flooding, and catastrophic slope failures, especially on slopes steeper than 45%, where saturated soils rapidly lose strength and collapse under their own weight.

4. Human-induced causes

Human activities increasingly amplify natural landslide risks. Unauthorised forest clearing for timber, vegetable farming, tea cultivation, and settlements removes tree roots that anchor soil.

This accelerates erosion and allows more water to infiltrate slopes.

Rapid population growth has also led to construction on unstable land without proper technical assessment. Common problems include:

Many rural roads lack retaining structures and drainage, making them highly vulnerable during heavy monsoon rains.

Simple examples to help land users

Conclusion: Reducing risk through awareness and action

Landslides result from a complex interaction of geology, water, topography, climate, and human intervention, with rainfall-triggered failures being the most common in tropical countries like Sri Lanka. The Central Highlands will always carry inherent landslide risks due to its geology and climate.

While landslides cannot be entirely prevented, their impacts can be significantly reduced. Effective mitigation requires coordinated action by Government agencies and communities through scientific planning, sound engineering, community awareness, early warning systems, and real-time monitoring.

Strict control of development on steep terrain, well-designed surface and subsurface drainage, protection and restoration of vegetation, and continuous monitoring of high-risk slopes, especially during monsoon periods, are essential. When these measures work together, sudden landslides can be reduced and communities can live more safely.

(The author holds a B.Sc. in Agricultural Engineering from Tokyo University and an M.Sc. in Soil and Water Management from the University of Wageningen. He is a specialist in watershed management and soil conservation, and a former Director of the Natural Resources Management Centre, Department of Agriculture, Sri Lanka. He has also worked with FAO in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh.)