Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Friday, 10 October 2025 05:29 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka’s electricity sector stands at a crossroads. The 2024 Act offered a path toward modernization, private investment, and fiscal sustainability. The 2025 amendments reflect a retreat into familiar—but flawed—territory.

This is not a debate between privatization and public ownership. It is a question of whether Sri Lanka can deliver reliable, affordable, and sustainable power in a constrained fiscal environment. Whether ideology will trump pragmatism. And whether the CEB can survive without the very reforms it is resisting.

The stakes are high. Electricity is not just a utility, it is the backbone of economic recovery, industrial growth, and climate resilience. Sri Lanka cannot afford to get this wrong.

Over the past two years, Sri Lanka's electricity sector has transitioned from a period of reform-driven ambition to reverting to centralization. The Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB)—long burdened by inefficiency, debt, and political inertia—was poised for transformation under the 2024 Electricity Act No. 36. But the 2025 amendments passed by the National People's Power (NPP) government have reversed course, reasserting state control and raising urgent questions about the sector’s future viability.

Over the past two years, Sri Lanka's electricity sector has transitioned from a period of reform-driven ambition to reverting to centralization. The Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB)—long burdened by inefficiency, debt, and political inertia—was poised for transformation under the 2024 Electricity Act No. 36. But the 2025 amendments passed by the National People's Power (NPP) government have reversed course, reasserting state control and raising urgent questions about the sector’s future viability.

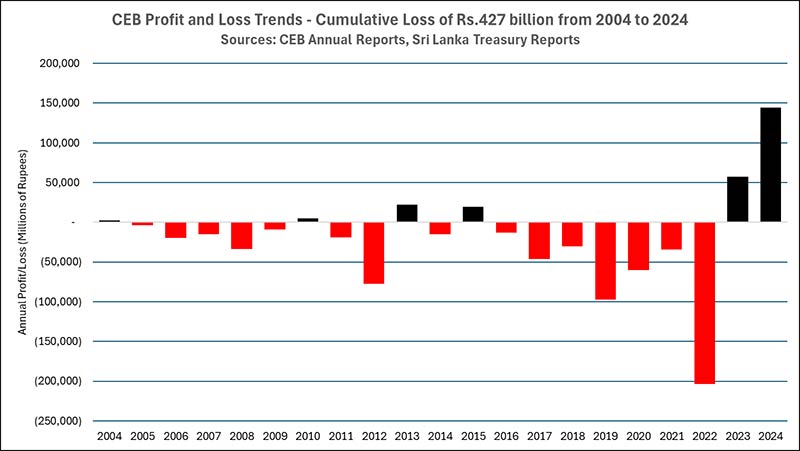

The CEB is a massive corporation with 2024 revenues of LKR 547 billion (~$1.8 billion). It rivals corporate giants like MAS, Brandix, Hayleys and John Keells. But, until IMF Extended Fund Facility (EFF) program imposed a requirement for cost reflective tariffs, CEB was frequently loss making with cumulative losses from 2004 to 2024 of about Rs. 427 billion (see Figure 1).

But this is not just a story about electricity or a large public sector corporation. It’s about a crucially important energy source. It is about whether Sri Lanka can modernize its infrastructure, attract investment, and deliver reliable, sustainable and lower cost power without repeating the mistakes of the past.

Figure 1 CEB Profit and Loss Trends

The 2024 Electricity Act No. 36: A Market-Oriented Blueprint

The 2024 Electricity Act represented a significant initiative to restructure the CEB and liberalize the electricity market to enable delivery of cost-effective and reliable electricity in a sustainable manner. The Act sought to facilitate increased private sector participation and investment in the sector, addressing longstanding inefficiencies and underinvestment within these areas. The Act proposed:

Unbundled CEB into Independent Corporate Entities by splitting the CEB into distinct entities to improve competition, efficiency and transparency:

• Generation: Divided by technology—coal, large hydro, oil/gas, and renewables.

• Transmission: The National Transmission Network Service Provider, mostly government-owned, holds and manages transmission assets, operates and maintains the network, and invests in its development. Other entities may be granted transmission sub-licences.

• Distribution: Handled by four independent companies plus LECO.

• Support Functions: Specialized entities for procurement, trading, and retail supply.

Established a Wholesale Electricity Market in a phased rollout, allowing generators and distributors to transact through transparent bidding and contracts, with the Public Utilities Commission of Sri Lanka as regulator.

Created a National Electricity Advisory Council as a statutory body with institutional independence, intended to provide broad-based, expert advice on electricity policy and regulation.

Encouraged Open Access and Private Sector Participation

• Permitted open access to the transmission network, enabling private generators to sell directly to distributors.

• Encouraged public-private partnerships and allowed listing of successor companies on the stock exchange.

• Private investment was explicitly welcomed in generation, distribution and transmission. Large hydropower assets remained state-owned.

Established a National System Operator (NSO), a wholly State-owned corporation responsible for real-time dispatch, grid management, scheduling and balancing, and overseeing bulk transactions between generators and distributors, and planning.

Provided a Transition Plan and Employee Protections

• CEB’s assets and liabilities were to be transferred to successor companies via a process managed by the Power Sector Reform Secretariat.

• Employees were given options to transition to new entities with preserved benefits; or opt for voluntary retirement.

• A dedicated fund was established to manage pensions and provident funds.

Sri Lanka Electricity (Amendment) Act, No. 14 of 2025: Ideology Over Investment?

The NPP government’s amendments reflect a different vision—one rooted in centralized control, public ownership, and cautious reform. The Sri Lanka Electricity (Amendment) Act, No. 14 of 2025 introduced several consequential changes that significantly altered the reform trajectory set by the Electricity Act No. 36 of 2024. Here are the most impactful changes:

Structural Reversal and Governance Centralization

• National Electricity Advisory Council replaced by a Minister-appointed committee, reducing institutional independence.

• Boards of successor companies are appointed by the Minister, with Treasury and Ministry representation—reintroducing political influence into operational governance.

Ownership and Licensing Restrictions

• Generation and distribution licenses are restricted to state-owned entities only. It blocks private sector entry into grid operations.

• Cross-ownership limits imposed: Private companies cannot hold more than 5% in generation and distribution companies simultaneously, discouraging integrated private investment. If LECO or LTL eventually gets listed, divesting these assets will become challenging as companies with financial and technical capacities may be precluded from bidding.

• Curiously LTL with 894+ MW of thermal and renewables generators, is now within the transmission company, creating a potential conflict of interest.

Fragmentation Instead of Functional Unbundling

• Aggregates generation and distribution (including LECO), into successor companies under Treasury ownership—with only a vague promise of future disaggregation.

• Recreates the vertically integrated CEB in fragmented form, preserving inefficiencies and union dominance, and increasing costs, rather than achieving the functional separation and competition that true unbundling was meant to deliver. •More concerning is that safeguards against future rebundling have been removed, undermining efforts to attract private investment.

Shift in Dispatch Philosophy

• The 2024 Act emphasized least-cost economic dispatch. The 2025 amendment replaces this with security-constrained economic dispatch, prioritizing reliability and system stability over cost optimization. While this aligns with global practices for grid resilience, it may increase costs unless paired with efficiency reforms.

• This approach implies a preference for “dispatchable” generation, which is CEB identifies mainly as thermal generation. Intermittent sources such as solar and wind are given lower priority, even though they can be made dispatchable at lower cost, as demonstrated in other countries.

Policy Realignment

• Although the NPP government aims to green Sri Lanka's power sector, there is also support for including natural gas as a clean energy source to help meet greenhouse gas reduction targets. While it is cleaner than coal, few countries consider natural gas as “clean energy”.

• However, the structural and market changes may hinder private investment in renewables, especially if procurement remains opaque or politically influenced.

Entrenched Benefits: Ring-Fencing Inefficiency

Perhaps most tellingly, the 2025 Act seems to ring-fence the generous salaries, allowances, and overstaffing that have long characterized the pre-reform CEB. These protections—while politically aligned with the NPP Government—undermine the very efficiencies that greater private sector participation could have delivered under the 2024 framework. The NPP government has signalled its intention to sign a collective agreement that will also bind the successor companies to guaranteeing several existing benefits and processes.

It is perfectly understandable that CEB employees would do their utmost to preserve the benefits they have enjoyed. Any workforce would. But it is the role of government to act in the interest of all Sri Lankans—not just one segment. Protecting entrenched privileges at the expense of national progress is a short-sighted bargain.

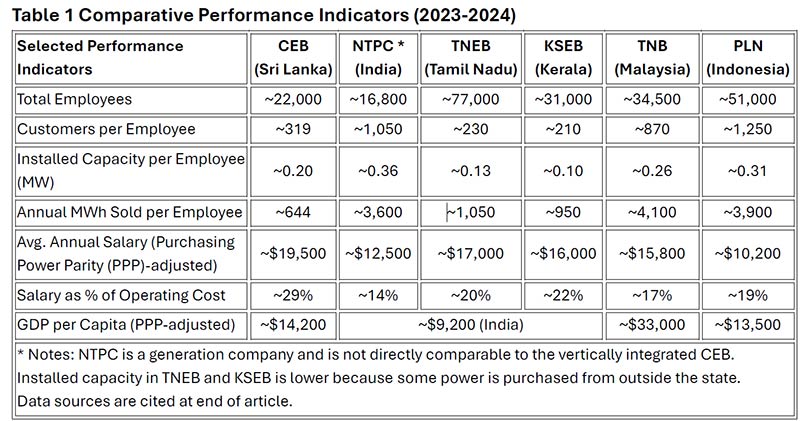

Table 1 shows CEB's productivity is similar to some Indian utilities but lags East Asian ones, while its salary costs are higher than those of its peers.

Financing in a Post-Reform Landscape

Here lies the paradox. The 2025 Act reinforces state control—but under the IMF agreement, the government ability is constrained to offer sovereign guarantees or expand public borrowing to fund CEB investments. The very tools that once sustained the CEB—Treasury bailouts, state-backed loans—are now effectively off the table.

The 2024 Act was designed precisely to address this constraint. By permitting private ownership in generation and distribution and in transmission, it aimed to attract capital without burdening the state. It offered a pathway for independent power producers, renewable developers, and distribution operators to invest, innovate, and expand the grid.

The CEB anticipates needing $5 billion in new capital investment up to 2044, compared to $1.2 billion in capital investment made in the preceding ten years. But the 2025 amendments have made investment less attractive by limiting cross-ownership, tightening licensing, and increasing political oversight. With no sovereign guarantees or strong private involvement, the CEB now faces a shortage of capital.

What’s Left on the Table?

Ultimately, to effectively mobilize the required investment, the NPP Government will need to balance the constraints of the new legislative framework with innovative financing mechanisms, regulatory clarity, and a willingness to partner with both international and domestic stakeholders. There may be yet a few financing options:

• Multilateral Finance: Institutions like the World Bank, AIIB and ADB may offer concessional loans, sector or policy loans, equity, or green bonds, but these funds are limited and come with policy conditions and limited flexibility.

• Bilateral Finance: Countries with strategic energy interests—India, China, Japan, EU—may offer targeted financing, but often with geopolitical strings attached.

• Ring-Fenced Project Finance: Special Purpose Vehicles for renewables could attract private capital but require regulatory clarity and credible governance. The experience with the Adani Wind Farm Project is not encouraging.

• Tariff Reform: Raising prices to reflect true costs in line with the IMF EFF has generated internal cash flow, and profits, but remains politically sensitive.

• Asset Recycling: Monetizing non-core assets could offer short-term relief, but not long-term sustainability.

Yet, unless bold reforms are enacted or the private sector is meaningfully brought into the fold, the sector risks remaining mired in chronic underinvestment and inefficiency. It will deter the vital capital essential for the nation’s progress. In such a scenario, it is ultimately Sri Lanka that will bear the cost.

References:

Sources for data in Table 1.

CEB Sales and Generation Data Book 2023. Retrieved from

https://www.ceb.lk/front_img/img_reports/1727249407Sales_and_Generation_Data_Book_2023.pdf,

CEB Statistical Yearbook 2024. Retrieved from

https://ceb.lk/front_img/img_reports/1751344341Statistical_Digest_2024.pdf

Ceylon Electricity Board. (2023). Annual Report 2023. Colombo: CEB. Retrieved from

Government of Tamil Nadu. (2024). Energy Department Performance Budget 2024–25. Chennai: Government of Tamil Nadu. Retrieved from

IMF. (2025). World Economic Outlook: October 2025 Edition. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO

Kerala State Electricity Board. (2023). Budget and Performance Report 2023–24. Thiruvananthapuram: KSEB. Retrieved from

https://ksebl-_budget-2023-24.pdf.

National Audit Office – CEB Audit 2023/ Retrieved from

NTPC Annual Report 2023. Retrieved from

https://ntpc.co.in/sites/default/files/annual-report/complete-reports/Annual%20Report%202023-24.pdf

PLN Statistics Indonesia 2023. Jakarta: PLN. Retrieved from

Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution Corporation (TANGEDCO). (2023). Data Card 2023–24. Chennai: TNEB Ltd. Retrieved from

TNB Integrated Report 2023. Kuala Lumpur TNB. Retrieved from

https://www.tnb.com.my/annualreport2023/images/downloads/TNB-IAR23.pdf

World Bank. (2024). Purchasing Power Parity Conversion Factors. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Retrieved from

(The writer holding a PhD, is a former World Bank Lead Energy Specialist.)