Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 2 September 2025 01:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

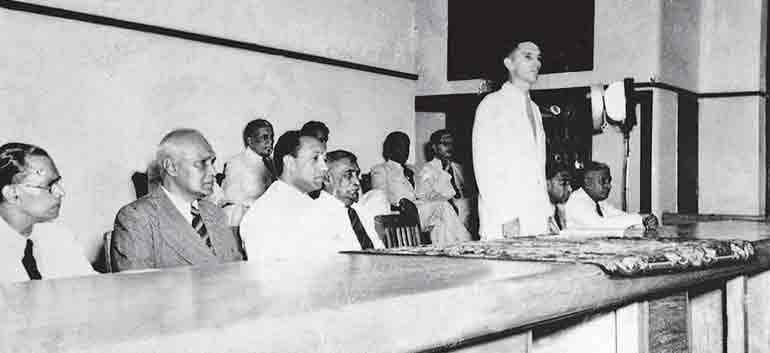

On 28 August 1950, a very special type of bank was set up in Sri Lanka, with a simple ceremony. In the words of the first Governor of the Central Bank of Ceylon, John Exter, the simplicity of the ceremony was not intended to “belittle the importance of the occasion…” but to be celebrated a decade or two later, looking back at its achievements in raising the living standards of the people of the country. It signalled the country’s resolve to chart its own financial destiny, to stabilise its currency, and to foster growth through sound monetary policy. 75 years later, today..., we look back to explore its evolution and achievements, to assess if the high hopes and good intentions that prevailed in 1950 have borne fruit…

From Currency Board to Central Bank

|

| Central Bank of Sri Lanka Governor Dr. Nandalal Weerasinghe |

For decades under British rule, the island’s money was governed by a Currency Board System, enacted under Ordinance No. 32 of 1884. While this system ensured currency stability, it constrained policy responses by tying the money supply directly to reserves, without any flexibility for nuance or support to growing domestic needs of a developing economy. Setting up the Central Bank of Ceylon was an initiative taken by Sri Lanka’s Finance Minister at the time, J.R. Jayewardene. This was a time when bank credit was provided primarily for the purpose of financing foreign trade; and the country wanted to look beyond the agricultural practices and excessive reliance on the traditional tea and rubber industries, to diversify into new sectors. For this, they sought to develop the banking system to adequately serve domestic businesses; to create employment opportunities and thereby enhance the livelihoods of the people of Sri Lanka.

A Federal Reserve Bank economist, John Exter was invited to Sri Lanka in 1948 to draft a blueprint. With a deep understanding of the challenges facing a young nation and reflecting on the central role monetary policy would play in overcoming them, the “Exter Report” laid the foundation for the Monetary Law Act No. 58 of 1949, which endowed the Central Bank with broad powers for issuing currency, regulating the banking system, managing international reserves and advising the Government on economic matters. Its initial objectives were broad; to stabilise domestic monetary values, maintain exchange rate stability, promote high levels of production, employment, and real income, and encourage full development of productive resources. “There are no financial sleight of hand tricks by which the standard of living could be suddenly raised,” Exter explains, “one of the first tasks of the Central Bank will be to attempt to devise ways and means of reducing the risks of lending money in Ceylon” – to enable the commercial banks, the mortgage lending institutions and the cooperative credit movements to make more credit available for the expansion of agriculture and to support the development of industries.

The economy in 1948: A fragile foundation

At independence, (then) Ceylon’s economy was largely agrarian. Although the country inherited key infrastructure from the British, the economy had a limited manufacturing base and remained heavily reliant on plantation agriculture, with tea, rubber, and coconut dominating exports. Ceylon’s financial sector comprised nine foreign banks of British, Indian, and Pakistani origin, which together accounted for over 60% of banking sector assets. There were only two domestic banks; one of which was a state bank, with a branch network covering nine major cities.

These banks, a few finance companies, savings institutions and insurance companies, were mainly focused on the urban, commercial sector and the plantation sector, leaving the rural domestic sector largely underserved. While the plantation sector influenced trade and commerce, banking and insurance, transport and manufacturing of plantation crops, there was very little interaction between the plantation and the non-plantation agricultural activities, thus failing to spark entrepreneurial spin-offs.

These banks, a few finance companies, savings institutions and insurance companies, were mainly focused on the urban, commercial sector and the plantation sector, leaving the rural domestic sector largely underserved. While the plantation sector influenced trade and commerce, banking and insurance, transport and manufacturing of plantation crops, there was very little interaction between the plantation and the non-plantation agricultural activities, thus failing to spark entrepreneurial spin-offs.

The country continued to depend on British markets and sterling reserves; that it remained vulnerable to external shocks and lacked industrial diversification. Under the Currency Board System in operation at the time, the Sri Lankan rupee was linked to the Indian rupee through the British pound sterling. Consequently, the amount of Sri Lanka rupees issued could only be increased or decreased based on the changes in the stock of Indian rupees held as reserves. As a result, the amount of money circulating in the economy could not be expanded or contracted in the face of balance of payments surpluses or deficits. Frequent changes in exchange control measures further complicated the situation.

Despite these challenges, Sri Lanka had a functioning administrative system and an educated population that exhibited potential for growth. What was missing was strategic planning and institutional support precisely what the Central Bank was designed to provide.

Role of the Central Bank – the guardian of stability

In the process of transferring power from the British Colonial Government to the newly established Government of Ceylon, the Central Bank of Ceylon took over the responsibility for monetary management from the Currency Board. According to Exter, monetary management affected every individual at a most vital point – his or her purse; reiterating that “true sovereignty is not the absence of foreign oversight, but the presence of domestic courage to reform, even when no one is watching.” In the international arena, the role of Central Banks was discussed extensively during this time, particularly with reference to their role in controlling inflation.

Referring to monetary conditions in Italy, which underwent serious bouts of inflation during and after the World War II and was subsequently able to stabilise its currency owing to an independent and far-sighted monetary policy, a general opinion emerged at the time that central banks should not be relied upon by governments to finance deficits. As lender of last resort, the Central Bank would always be ready to lend to commercial banks and thus make the banking sector almost invulnerable in times of crises. This together with the Central Bank’s supervisory function made it possible for the public to use the banking system with confidence. Exter explained that Central Banks could stimulate banks to increase their loans, to extend their tenures; and lower interest rates to expand their services to the public. However, he stressed that the Central Bank itself would have no dealings with the public.

Operationalising the Central Bank

The Central Bank of Ceylon took over the functions of the Board of Commissioners of Currency, through a transfer of capital; with initial capital of Rs. 15 million and a surplus of Rs. 10 million from the Board of Commissioners of Currency. Exter explained that in addition to issuing notes against its assets and holding the reserves of the commercial banks, the Central Bank would act as the Fiscal Agent and Financial Advisor to the Government. It also took over the functions of the clearing house, that facilitated the exchange of payments, securities, and other transactions, which was up until then, handled by the Imperial Bank of India. The Ceylon rupee was no longer defined in terms of the Indian rupee, and there was no longer a requirement for the maintenance of its convertibility through issuing and redeeming Ceylon currency. As the narrow and automatic powers of the Currency Board were replaced by the Central Bank of Ceylon with broad powers to administer and regulate the entire money, banking and credit systems, Exter also emphasised the importance of maintaining an independent monetary system.

Central Bank mandates, board compositions and independence

The Monetary Law Act of 1950 stipulated the composition of the Monetary Board; chaired by the Governor of the Central Bank and Secretary to the Treasury serving as ex-officio member, along with one additional independent member. As the complexity of the economy increased, the Bank’s responsibilities also evolved. By way of amendments to the Monetary Law Act in 2002, the Central Bank’s objectives were revisited to support a modern institution focused on economic and price stability, as well as the stability of the financial system. The Monetary Board was also expanded to five members to enhance private sector representation.

More recently, with the enactment of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act no. 16 of 2023 the Central Bank narrowed its focus further to price stability and financial system stability, grounded in clear statutory objectives and the operational independence to pursue them. The Board was expanded to further increase private sector representation and split into two separate Boards: one dedicated solely to Monetary Policy and the other, to govern the day-to-day activities of the Bank.

The Government representation was removed to distance fiscal considerations from the conduct of monetary policy – thereby enabling credible commitment to maintain low inflation. Strong accountability mechanisms and transparency requirements were established to reinforce and to legitimise this independence.

Today, the Monetary Policy Board is responsible for the formulation of monetary policy and the implementation of a flexible exchange rate regime in line with the flexible inflation targeting framework to achieve its prime objective of maintaining domestic price stability. This entails stabilising inflation around the targeted level while minimising disruptions to the real economy. The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), chaired by the Governor, is responsible for evaluating emerging economic developments and assessing macroeconomic projections; to make recommendations on the appropriate future course of monetary policy. Under the 2023 CBSL Act, the CBSL’s mandate was expanded to include: macroprudential policy, financial inclusion and deposit insurance, in addition to its traditional roles of monetary and exchange rate policy, foreign reserves management, currency issuance, payment systems regulation, bank supervision, statistical services, government advisory and fiscal agency functions.

Monetary and exchange rate policies

Until around 1960, the focus of Monetary Policy was on stabilising the economy. Subsequently, its focus shifted towards the development agenda, redirecting resources among sectors to promote import substitution and other industries. Being a small economy with limited domestic demand, Sri Lanka was one of the first countries in Asia to liberalise international trade (1977), replacing quantitative restrictions on imports with tariffs.

The policy reform package introduced with the economic liberalisation in 1977 included substantial financial market reform, export promotion through the establishment of export processing zones, new tax-based incentives to entice foreign investors, encouragement of private sector participation in economic activity, and the transition to a managed float exchange rate regime. This propelled the development of the industrial sector as a source of export earnings.

With the removal of import controls in the 1977 liberalisation efforts, the Central Bank replaced the Bank Rate with the Statutory Reserve Ratio (SRR) as its key monetary policy instrument to steer the economy. Subsequently, the Central Bank engaged in “open market operations” to manage liquidity and influence market interest rates. An interest rate corridor and a bidding system were introduced in 2001 to enable banks to bid based on their liquidity estimates. More recently, the policy rates, which formed the edges of the moving corridor were reunified into a single interest rate, to enhance the signalling effect. Over time, the operating target of Monetary Policy also shifted from reserve money to targeting interest rates.

Since 1948, Sri Lanka adopted a fixed exchange rate system linked to the British pound sterling, with controls on capital transactions, for nearly two decades. However, in the face of severe balance of payments difficulties, a dual exchange rate was introduced for specific transactions, which was subsequently unified in 1977 when trade and payments were extensively liberalised. Although the Rupee was allowed to float within a predetermined band since then, there have been periods when it was determined purely on the supply and demand for foreign exchange.

In 1994, controls on all current account transactions were lifted, which deepened the foreign exchange market. The band was maintained until mid-2000, when pressure on the exchange to depreciate intensified due to a host of factors ranging from unfavourable weather conditions to the sudden spike in global oil prices. As a result, the band was gradually widened, and the exchange rate was allowed to float freely in 2001. Central bank interventions in the market are now limited to stabilising the exchange rate in the face of excessive volatility or for building up international reserves.

Development of the financial sector

The nationalisation of the Bank of Ceylon and establishment of the People’s Bank set the stage for the expansion of the branch network to remote areas where no foreign bank ventured. Although this facilitated the propagation of a banking culture among the people, given the tendency for excessive reliance on non-commercial criteria for branch expansion and granting credit, the state banks became means of providing political patronage and expanding employment. Highlighting the difficulties of those who seek credit from government and commercial financial institutions, the Central Bank encouraged commercial banks to extend more credit to stimulate domestic production and development through medium and long-term facilities.

The development finance institutions were set up to support agriculture and industry, and refinance schemes were set up to extend credit for small-scale entrepreneurs. With economic liberalisation, the Central Bank engaged in reforms in the 1980s to modernise banking regulations, improve transparency, and encourage competition. While private and foreign banks re-entered the market in the 1990s, non-bank financial institutions, such as leasing companies and insurance firms, expanded rapidly. This growth prompted the Central Bank to supervise regulated non-bank financial institutions and, subsequently, microfinance entities. The new millennium ushered in a wave of technological transformation through digitisation and innovation as online banking, and mobile payments became mainstream and digital transactions across banks were unified via the LankaPay network.

The Central Bank also strengthened its regulatory framework, adopting international standards for risk management and financial reporting. Sri Lanka’s financial sector today is a blend of tradition and innovation with over 30 licensed banks, propagating a growing fintech ecosystem, including mobile wallet and blockchain pilots, and expanding green finance and sustainable investment initiatives. The Central Bank launched FinTech Regulatory Sandboxes to enable startups to test new financial technologies under controlled conditions; to encourage responsible innovation, identify regulatory gaps and support financial inclusion through mobile banking and microfinance. Although challenges remain, particularly in ensuring financial inclusion, managing debt, and adapting to global shocks, the financial sector today is more agile, transparent, and forward-looking than ever before.

External shocks and missed opportunities amidst modernisation

Despite the developments in the monetary policy arena and the financial sector, the Central Bank’s journey has not been without challenges. As a small island nation, Sri Lanka was susceptible to external shocks arising from high oil prices, natural calamities and the effects of climate change. Although the trade account was liberalised early, the Central Bank remained somewhat cautious about opening its markets to capital flows. The Central Bank also ensured the gradual adjustment of the exchange rate to prevent a major misalignment with respect to the other major international currencies. Together, these measures helped the country escape the brunt of the East Asian Crisis of 1997.

Over time, however, the world continued to become more and more integrated, and by 2006, Sri Lanka had accommodated the more volatile, short term foreign borrowings and foreign investments in government securities to a limited extent. Thus, by the time the US Sub Prime issues spread throughout the world, the Sri Lankan economy was subjected to a sudden withdrawal of short-term capital, which led to a sharp reduction in international reserves. As the US and other major economies around the globe slowed down, Sri Lanka’s economy was also affected.

Sri Lanka has experienced prolonged periods in which the Government’s borrowing needs dictated monetary policy, leading to inflation, currency instability, and a loss of Central Bank independence. In the face of persistent fiscal deficits, and when borrowing became difficult, the Central Bank has been pressured to finance the deficits, frequently through money printing which tends to give rise to inflationary conditions. The Central Bank was also subjected to terrorist attacks in 1996, where explosion of bombs not only destroyed the building but also took away the lives of several employees and hurt many others. The Central Bank operated from its Centre for Banking Studies with a minimum workforce until it returned to its newly built Head Office, at its 50th anniversary.

Upon its return, the Central Bank embarked on a modernisation program that incorporated several advanced technologies at the time including the Real Time Gross Settlements mechanism and Cheque Imaging and Truncation System, that brought about efficiencies in payment systems.

Sri Lanka also experienced a series of missed opportunities, resulting from policy inconsistencies and separatist agendas, followed by several economic missteps, which prevented the country from attaining the high-growth trajectory envisioned by the Central Bank. Sri Lanka approached the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for assistance on several such occasions. In 2022, Sri Lanka became the first Asian country in 20 years to default on its sovereign debt and had to engage in domestic debt optimisation process and undertake the restructuring of its foreign debt in 2023-24.

Since then, the IMF has supported the country’s economic recovery through a multi-billion-dollar Extended Fund Facility (EFF) agreement focused on fiscal discipline, debt restructuring, state enterprise reform, banking sector governance, anti-corruption efforts, and the use of market signals to help the country regain market access, boost investor confidence, and protect itself from future shocks.

Since assisting the banking sector adapt to Y2K issues in 2000, the Central Bank embraced technology to bring more Sri Lankans into the formal financial system and reduce reliance on cash. These include efforts to unify digital payments, introduce QR code-based transactions for small merchants, and to develop frameworks for digital banking licenses, and e-KYC. Overall, technology has now become central to how central banks maintain monetary stability, regulate financial systems, and serve the public. Recognising the importance of evidence-based decision making, the Central Bank set out to collect data on the economy early on. The monthly bulletin with monetary and banking statistics; has been issued since 1951 to meet the needs of the commercial banks, economics students and the public.

The Central Bank also communicates its decisions, their implications as well as other relevant information from time to time, in line with emerging technologies and global trends in Central Bank communication, to enable the public to understand its decisions against policy alternatives, so that they can make informed choices. Central banks are also increasingly using artificial intelligence (AI) and advanced analytics to process vast amounts of financial and economic data, which is reshaping the very DNA of central banking.

They are already modernising their information technology (IT) infrastructure, promoting cloud services, to improve scalability and resilience, and Open Banking, to allow third-party developers to build apps and services around financial institutions, leading to more personalised financial services, greater competition and innovation, for enhanced customer experience. From AI-driven policy to blockchain-backed currencies, Central Banks are no longer just guardians of stability but becoming architects of the future. For countries like Sri Lanka, this digital transformation is not just about modernisation – it’s about empowerment, inclusion, and resilience.

Conclusion

From the vibrant hopes at its founding in 1950 to the trials of sovereign default, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka’s story over the past 75 years reflects the arc of the nation’s economic evolution marked by aspiration, innovation, turbulence, and renewal. Its original objectives of monetary sovereignty – to stabilise prices, support exchange rates, and fuel production – set the groundwork for decades of economic policy. From managing currency and inflation to guiding trade and development, the Central Bank has been a cornerstone of Sri Lanka’s economic journey. It has weathered wars, political shifts, global recessions, economic upheavals, pandemics, and defaults.

Throughout these challenges, the Central Bank has refined its mandate, expanded its operational prowess, and consistently strived to serve the people, while guiding the financial sector to adapt and evolve along the way. The journey is far from over. As Sri Lanka embraces digital transformation, climate finance, and global integration, it will continue to be a cornerstone of national progress. In the words of John Exter, “A central bank is not just a financial institution – it is a symbol of sovereignty.”

Yet, challenges loomed with political influence blurring its independence as runaway inflation and sovereign default tested the resolve of the leaders of the Central Bank, revealing systemic vulnerabilities. But adversity bred reform as the 2023 Central Bank Act restructured governance, strengthened independence, enshrined accountability, and renewed its mandate in a modern legal framework. The history of the Central Bank extends beyond bureaucratic architecture or financial dashboards. It is a story of a nation learning to steer its own destiny – emerging from colonial structures, navigating global currents, and striving toward sovereign, stable growth.

Every digital payment infrastructure, every policy shift, every governance reform reflects a commitment to building not just an institution, but a foundation for prosperity. From Exter’s pioneering work to the present-day boards shaping monetary and broader policies, the Central Bank’s journey embodies resilience and adaptation. Even when battered by storms, the institution remained central – reminding us that well governed institutions, when recalibrated, can renew-and that financial failures can become springboards for stronger, more transparent systems.

Seventy-five years ago, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka was born out of hope and necessity. Today, it stands as a testament to resilience, adaptation, and the enduring pursuit of economic stability. When guided by independence, integrity, and public mission, a central bank becomes a pillar of national progress. Despite its tests and trials, Sri Lanka’s central bank carries the promise of a future grounded in stability, inclusivity, and shared prosperity, as it celebrates its 75th anniversary with yet another simple ceremony.

(The writer is Director, Centre for Banking Studies at CBSL.)