Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 6 December 2025 00:26 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The name “Ditwah” was suggested by Yemen, referencing the Detwah Lagoon on the island of Socotra, a UNESCO World Heritage site celebrated for its saline beauty. It is a poetic but grim irony. For Sri Lanka, the name Ditwah will not be remembered for natural beauty, but for the saline intrusion that flooded coastal villages and the relentless deluge that buried the central hills.

The name “Ditwah” was suggested by Yemen, referencing the Detwah Lagoon on the island of Socotra, a UNESCO World Heritage site celebrated for its saline beauty. It is a poetic but grim irony. For Sri Lanka, the name Ditwah will not be remembered for natural beauty, but for the saline intrusion that flooded coastal villages and the relentless deluge that buried the central hills.

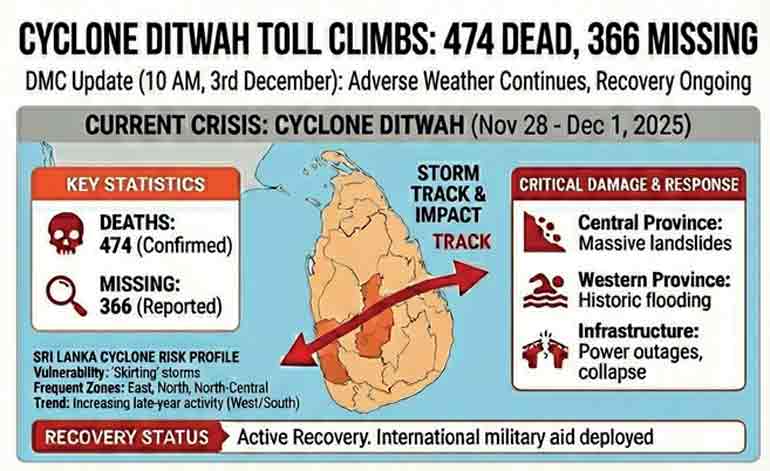

As the flood waters recede from the Kelani and Mahaweli river basins, they reveal more than just mud and debris. They lay bare the brittle skeleton of Sri Lanka’s disaster management infrastructure. With a death toll confirmed at 474, over 366 missing (as of 3rd December), and 1.1 million citizens affected, Cyclone Ditwah is not merely a meteorological anomaly. It is an administrative stress test that the State has failed.

For the readers of the Daily FT, who understand that national resilience is the bedrock of economic stability, this disaster serves as a critical case study. The catastrophe was not caused merely by the wind, but by a widening gap between scientific warning and administrative action.

The physics of failure: A predictable surprise

To understand the magnitude of the administrative failure, one must first accept the physics of the hazard. Cyclone Ditwah was distinct because of its lethargy. Unlike typical tropical cyclones that transit across landmasses relatively quickly and minimising exposure time, Ditwah exhibited a “slow-moving” behaviour.

The system “stalled” as it tracked north-north westwards, moving at excruciatingly slow speeds of 3 km/h to 7 km/h for extended periods. This stalling effect allowed the cyclone’s feeder bands to act as a continuous pump, drawing moisture from the Bay of Bengal and dumping it directly into the central hill country. Districts such as Kandy, Nuwara Eliya, and Badulla recorded rainfall exceeding 500mm within a 24-hour window which is nearly a quarter of their annual rainfall in a single day.

This was not a surprise event. The Department of Meteorology tracked the cyclogenesis from its formation on November 26. It issued “Red Alerts”. The science was accurate but the failure lay in the translation of that science into survival.

The “last mile” disconnect: A historical regression

The most damning indictment of the response is the collapse of “last mile” communication. In previous successful disaster mitigations, local early warning mechanisms such as temple bells, loudspeakers, and community runners played a vital role in bridging the gap between Colombo’s data and the village’s reality.

During Ditwah, this mechanism fell silent. Reports from Gampola indicate residents were asleep when a “13-foot wall of water” hit their village. These citizens are likely to have known it was raining but they had no conception of the specific, imminent landslide risk. The State failed to translate a meteorological “Red Alert” into an intelligible “Evacuate Now” order for specific landslide-prone zones.

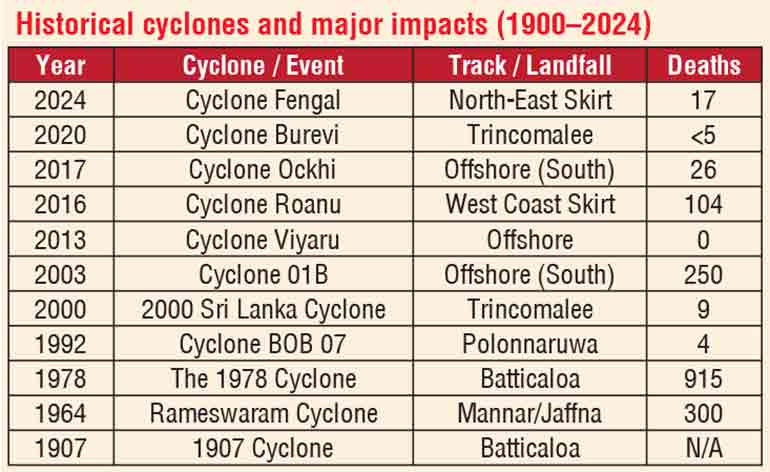

This represents a startling regression in capability. A comparative analysis of historical data reveals that Sri Lanka possessed the competence to manage this exact scenario just five years ago.

In stark contrast, Ditwah has resulted in mass casualties not seen since the 1978 Cyclone. We moved from the “Zero Casualty” success of 2020 back to the chaos of the past, proving that the machinery of the State has rusted in the intervening years.

The fragility of critical infrastructure

For the business community, the destruction of physical infrastructure presents a bleak economic outlook. The resilience of a nation is measured by the durability of its grid and its roads, and Ditwah has shown ours to be dangerously brittle.

We witnessed a catastrophic failure of the “Water-Energy Nexus.” When the Greater Kandy Water Treatment Plant at Gatambe flooded, it was expected. What was unacceptable was that even after waters receded, the plant remained offline because the grid had collapsed, and there was no backup power to run the sludge pumps.

The collapse of a single high-voltage transmission tower connected to the Randenigala power plant severed power to Mahiyanganaya, Ampara, and Vavuniya. That a single point of failure could cause such widespread blackouts raises serious questions about the redundancy and maintenance of our high-tension network.

Furthermore, the destruction of the distribution network in Badulla where landslides didn’t just snap lines but buried poles means we are looking at total reconstruction, not simple repair.

This infrastructure paralysis mirrors the “Infrastructure Collapse” of the 1964 Rameswaram Cyclone, where the Talaimannar Pier and rail links were severed. Sixty years later, our grid remains just as vulnerable to singular shocks.

‘As the flood waters recede from the Kelani and Mahaweli river basins, they reveal more than just mud and debris. They lay bare the brittle skeleton of Sri Lanka’s disaster management infrastructure’

The comparative mirror: India’s “Zero Casualty” model

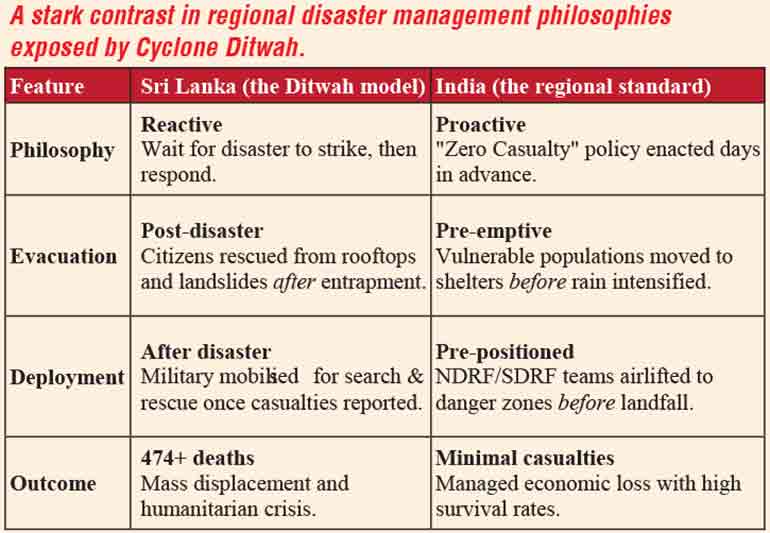

Perhaps the most uncomfortable lesson comes from looking North. Both Sri Lanka and the Indian states of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh faced the same meteorological system. The outcomes, however, were vastly different.

India operates on a “Zero Casualty” policy. In Tamil Nadu, District Collectors were given autonomy to close schools and open relief camps before the rain intensified. They mobilised 12 NDRF teams and airlifted them to vulnerable districts like Cuddalore before the cyclone arrived.

In contrast, Sri Lanka’s model remains reactive. We deploy the military for search and rescue after the landslide has occurred, rather than mobilising civil administration to move people before the soil saturates. The disaster management apparatus appeared paralysed until the casualty counts began to rise.

Sovereignty and the aid trap

The arrival of the Indian Navy’s INS Vikrant and the deployment of Indian Air Force C-17s under “Operation Sagar Bandhu” was a welcome humanitarian gesture. However, it also underscored a severe sovereignty gap.

That a sovereign nation required foreign military aircraft to rescue 121 of its own citizens stranded in inaccessible areas highlights a lack of domestic investment in heavy-lift and search-and-rescue assets. We cannot claim to be an aspiring regional hub if we cannot reach our own hinterland during a crisis. While international aid is a hallmark of diplomacy, reliance on it for basic first response is a hallmark of state failure.

From reaction to resilience

The Opposition will undoubtedly call for inquiries, and the Government will likely appoint committees. But a forensic analysis of Cyclone Ditwah suggests we do not need more reports; we need a fundamental shift in doctrine.

We must move from a “reactive rescue” model to a “proactive prevention” model. This requires reviving the community alarm systems that bridge the gap between Colombo’s data and the village’s reality. It requires auditing the grid for single points of failure like the Randenigala tower and ensuring critical utilities like water plants have autonomous power backups. Most importantly, it requires empowering District Secretaries with the authority to order pre-emptive evacuations without waiting for central clearance.

Cyclone Ditwah has cost us 474 lives and billions in economic damage. If we simply rebuild what was there, we are merely setting the stage for the next tragedy. We must build back not just better, but smarter.

Three key questions for Parliament

A call to action for the Opposition and Civil Society.

1. Who silenced the “Temple Bells”?

In 2020 (Cyclone Burevi), District Secretariats successfully evacuated 75,000 people before landfall, resulting in fewer than five casualties. In 2025, residents in Gampola drowned in their sleep because “Red Alerts” never translated into ground-level evacuation orders. Why was the successful “Zero Casualty” protocol of 2020 abandoned, and who is accountable for the failure of the “last mile” warning system?

2. Why is national security dependent on a single tower?

The report confirms that the collapse of a single high-voltage transmission tower connected to the Randenigala power plant severed power to three major districts (Mahiyanganaya, Ampara, Vavuniya). How can a critical national grid lack basic redundancy, and why did water treatment plants (like Gatambe) lack the backup generation required to pump sludge, leaving cities without water days after the rain stopped?

3. Is our sovereignty outsourced?

While India’s assistance is appreciated, the deployment of foreign military assets (IAF C-17s and Mi-17 helicopters) to rescue 121 Sri Lankan citizens from inaccessible areas is a startling admission of domestic failure. Does the Ministry accept that after 77 years of independence, the State still lacks the heavy-lift air capacity and swift-water rescue boats required to save its own citizens from a predictable monsoon event?

(The author is a telecommunications engineer turned environmental and wildlife conservationist and citizen scientist, as well as a documentary filmmaker focused on wildlife. His core focus lies in driving policy-level changes needed to strengthen environmental and wildlife conservation in Sri Lanka.)