Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday, 10 February 2026 04:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

If the current Government’s development agenda is genuinely ambitious, then there is a clear mismatch between the growth implied by that ambition and the growth described in the Central Bank’s outlook. A strategy that settles for 4–5% risks normalising mediocrity rather than mobilising the economy for take-off. Reconstruction-led and consumption-led expansions can lift GDP in the short run, but they do not, by themselves, deliver the productivity and export breakthroughs needed for sustained 7–8% growth

If the current Government’s development agenda is genuinely ambitious, then there is a clear mismatch between the growth implied by that ambition and the growth described in the Central Bank’s outlook. A strategy that settles for 4–5% risks normalising mediocrity rather than mobilising the economy for take-off. Reconstruction-led and consumption-led expansions can lift GDP in the short run, but they do not, by themselves, deliver the productivity and export breakthroughs needed for sustained 7–8% growth

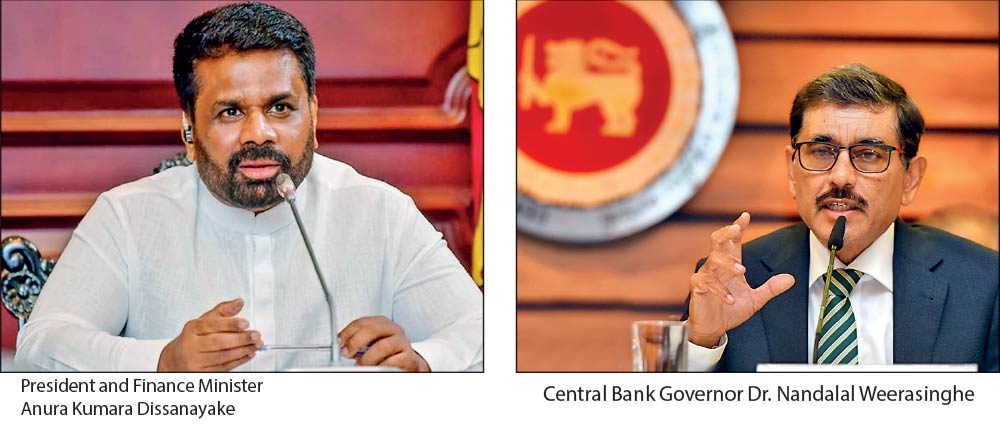

The Central Bank Governor Dr. Nandalal Weerasinghe’s recent remarks projecting 4–5% growth in 2026 and highlighting improving reserves, lower inflation, and financial stability have been widely welcomed. After the trauma of Sri Lanka’s economic crisis, any sign of normalcy is understandably reassuring. Yet this optimism needs to be read carefully. What is being presented is largely a story of stabilisation and recovery, framed in the familiar IMF language of macroeconomic management. That is necessary—but it is not the same as a pathway to durable growth.

The Central Bank Governor Dr. Nandalal Weerasinghe’s recent remarks projecting 4–5% growth in 2026 and highlighting improving reserves, lower inflation, and financial stability have been widely welcomed. After the trauma of Sri Lanka’s economic crisis, any sign of normalcy is understandably reassuring. Yet this optimism needs to be read carefully. What is being presented is largely a story of stabilisation and recovery, framed in the familiar IMF language of macroeconomic management. That is necessary—but it is not the same as a pathway to durable growth.

The first issue is the nature of the projected growth itself. A 4–5% expansion can occur for many reasons, not all of which strengthen an economy in the long run. In this case, a significant part of the momentum is expected to come from post-cyclone reconstruction and public investment. This will boost activity in construction and related services and create jobs in the short term. But such growth is typically demand-led and temporary. It raises GDP without necessarily expanding the country’s productive capacity, technological capability, or export competitiveness. Once the reconstruction cycle fades, so may the growth.

Durable growth

This points to a crucial distinction that often gets blurred in public debate: economic recovery and durable growth are not the same thing. Recovery means returning to a more normal macro environment—lower inflation, a more stable exchange rate, some rebuilding of reserves, and a functioning financial system. Durable growth, by contrast, requires rising productivity, structural change, and a stronger export base. Sri Lanka can achieve the first without securing the second. Indeed, that is precisely what happened in earlier post-crisis episodes, where short-lived recoveries were followed by renewed external stress.

The Governor’s narrative is best understood as an IMF-style stabilisation narrative. Its centre of gravity is macro control: inflation targets, policy rates, reserves, debt service, and financial-sector resilience. These are the right tools for preventing another crisis. But they are not a strategy for accelerating development. IMF programs are designed primarily to restore confidence, manage risk, and stabilise the macroeconomy. They are not designed to answer the core development questions: What will Sri Lanka produce? What will it export? How will productivity rise? Which sectors will drive long-term growth?

Seen in this light, a projected 4–5% growth rate is best described as moderate recovery growth. It may be entirely plausible—especially if driven by reconstruction and public spending—but it is not the kind of growth that closes income gaps, absorbs underemployment at scale, creates sustained fiscal space, or materially reduces debt burdens. Countries that have successfully caught up in Asia typically sustained 7–8% (or higher) growth for long periods, powered by export expansion, industrial upgrading, and continuous learning.

If the current Government’s development agenda is genuinely ambitious, then there is a clear mismatch between the growth implied by that ambition and the growth described in the Central Bank’s outlook. A strategy that settles for 4–5% risks normalising mediocrity rather than mobilising the economy for take-off. Reconstruction-led and consumption-led expansions can lift GDP in the short run, but they do not, by themselves, deliver the productivity and export breakthroughs needed for sustained 7–8% growth.

There is also a risk that reconstruction-driven growth will recreate old external vulnerabilities. Large-scale rebuilding increases demand for cement, steel, fuel, machinery, and transport services—many of which are import-intensive in Sri Lanka. This means higher growth can go hand in hand with a widening trade deficit, renewed pressure on foreign exchange, and imported inflation. The Governor has rightly warned about inflationary and external pressures, but the deeper issue is structural: without a parallel expansion of export capacity and domestic production of tradables, stimulus-driven growth can quickly collide with the same constraints that caused past crises.

The improvement in reserves and the claim that debt service is “manageable” are positive developments. But they should be treated as buffers, not proof of long-term security. Sri Lanka’s recent history shows how quickly reserves can be run down when imports surge, exports disappoint, or global conditions tighten. Reserves buy time. They do not, by themselves, change the underlying growth model.

Similarly, the focus on bringing inflation back towards target and maintaining steady policy rates reflects sound central banking. Price stability and financial-sector resilience are public goods. But an inflation target is not a growth strategy. Durable growth comes from investment in productive capacity, from learning and technological upgrading, from moving into higher-value activities, and from building competitive export sectors. Without these, macro stability becomes an exercise in maintenance rather than transformation.

Stability is essential. Without it, nothing else is possible. But stability is not a development strategy. It is the foundation on which a strategy must be built. The real test for policymakers now is not whether they can keep the economy stable, but whether they can articulate and implement a credible growth strategy that turns stability into momentum and recovery into transformation

Stability is essential. Without it, nothing else is possible. But stability is not a development strategy. It is the foundation on which a strategy must be built. The real test for policymakers now is not whether they can keep the economy stable, but whether they can articulate and implement a credible growth strategy that turns stability into momentum and recovery into transformation

Structural reforms

The repeated reference to “structural reforms” also needs to be treated with care. In policy practice, this often means reforms to pricing, state-owned enterprises, taxation, and public finance management. These may improve efficiency and governance, and they matter. But in development economics, structural transformation means something more demanding: a change in what the country produces, how it produces, and what it sells to the world. It means shifting resources into higher-productivity, more technologically advanced, and more export-oriented activities. Without that shift, an economy can be well-managed and still remain fragile.

What is striking in the Governor’s statement is not that it is wrong, but that it is incomplete. We hear a great deal about stability, recovery, and resilience. We hear much less about the growth strategy itself. Which sectors are expected to lead the next phase of growth beyond construction and consumption? How will exports be diversified and upgraded? What is the plan for skills, technology, and productivity? How will private investment be steered toward tradable, foreign-exchange-earning activities?

These are not academic questions. They go to the heart of whether Sri Lanka is merely staging another rebound or beginning a genuine breakthrough. The country’s repeated crises have shown that returning to “normal” is not enough if the underlying growth model remains unchanged.

In sum, the Central Bank Governor’s optimism should be understood for what it is: a stabilisation narrative, not yet a development strategy. It tells us that the economy is becoming calmer, more predictable, and less crisis-prone—and that is a real and necessary achievement. But it does not yet tell us how Sri Lanka will grow fast enough, long enough, and differently enough to escape its long-standing cycle of weak exports, external vulnerability, and stop–go growth.

A recovery built on reconstruction, consumption, and macro control can deliver 4–5% growth. But the government’s own ambitions—and Sri Lanka’s development needs—require 7–8% sustained growth driven by productivity, exports, and structural transformation. That kind of growth does not emerge automatically from stability. It must be designed, coordinated, and pursued through a clear strategy for production, learning, and upgrading.

Stability is essential. Without it, nothing else is possible. But stability is not a development strategy. It is the foundation on which a strategy must be built. The real test for policymakers now is not whether they can keep the economy stable, but whether they can articulate and implement a credible growth strategy that turns stability into momentum and recovery into transformation. Until that strategy is clearly on the table, Sri Lanka’s current optimism—welcome as it is—should be read with caution, not complacency.