Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 14 October 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The case of a bankrupt company

What do you think of a private company which is indebted to the hilt, does not earn enough to repay its debt and experiences a low sales growth which is declining year after year? Surely, it is a problem company needing quick fixing.

If its capital has completely been eaten up, it is said to be a bankrupt company which, as those in the market would say, is in the red. To convert it into green, capital has to be brought in from outside, while its operations are restructured. If this is not done, the private company will go under and has to stop operations before the authorities would force it to close shops.

Sri Lanka Incorporated: Fast moving toward bankruptcy?

Now consider the parallel between this company and the country called the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. The total public debt incurred by its Central Government is about 83% of the country’s total output, known as the Gross Domestic Product or GDP. When the Central Government’s borrowings from the Central Bank and State banks are also added, the total debt increases to 85% of GDP. That number includes only the foreign borrowings of the Central Government. In addition, private sector entities also have made foreign borrowings amounting to some $ 21 billion.

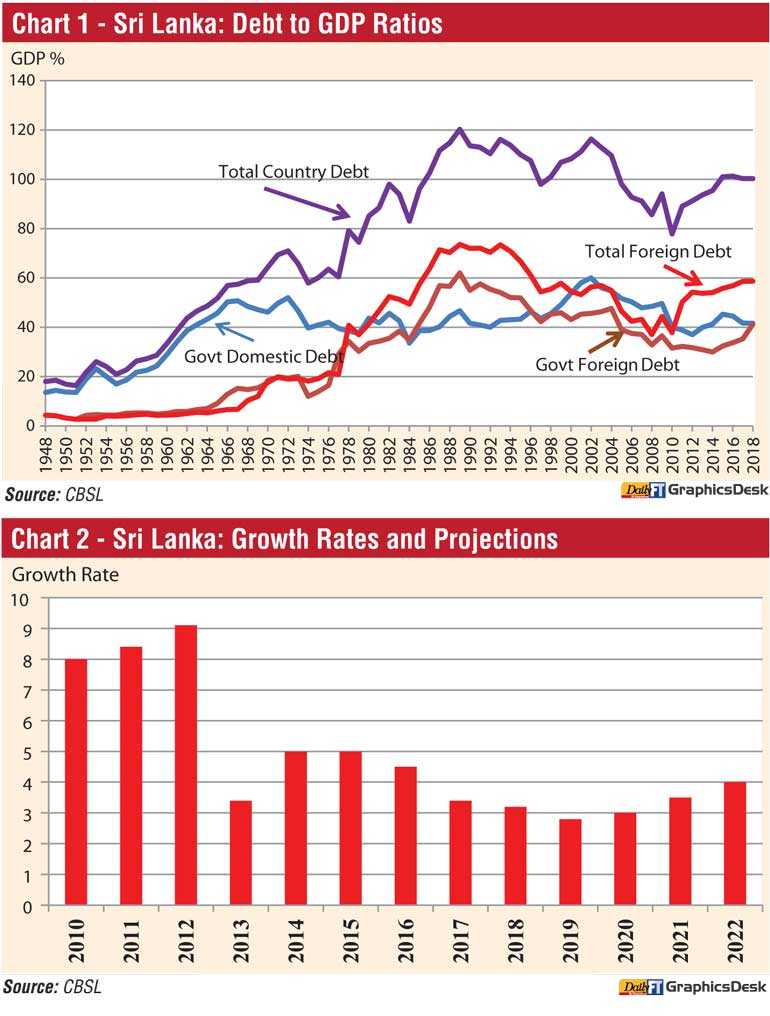

When that number is also added to the Central Government borrowings to represent the total country borrowings, it rises to 100% of GDP in 2018. Sri Lanka was able to reduce the share of these borrowings from a peak of 116% of GDP in 2002 to 77% in 2010. This is shown in Chart 1. But since then, they have been rising ominously mainly due to the increases in foreign debt contracted by both the Central Government and the private sector.

To complicate the ominous economic situation, economic growth has been falling continuously from 9% in 2012 to 3% in 2018. The growth projections for 2019 have been even below 3% with no hope of economic recovery during the next three-year period, as shown in Chart 2.

Expanding the debt profile in a slow real growth era

Unlike a private company in a similar situation, Sri Lanka is not yet a bankrupt country that should go into compulsory liquidation.

With its single digit inflation of around 4%, its Government can still repay domestic debt by either borrowing from the domestic economy or by printing new money. The country can still access foreign commercial markets to raise foreign exchange funds to repay its foreign debt. However, the country’s debt profile is changing for the worse year after year pushing it to the edge. Presently, annual debt repayment obligations are almost equal to the total Government revenue. In the next few years, it will exceed the revenue levels making it necessary for the country to borrow in larger volumes and repay its debt.

This debt recycling has a limit since no country can continue to expand its debt profile unless it has comfortable real economic growth to back such borrowings. In this connection, the danger signs have already been shown by the low economic growth in the recent past with no prospect for economic recovery in the next few years. Hence, though it may not be fully bankrupt today, it is pretty much on the way to bankruptcy.

Hence, without further borrowing, the country cannot maintain its unblemished track record of meeting all foreign debt obligations in time. The casualties in this backdrop are ever-rising foreign debt, depleted foreign reserves, falling exchange rate, stalling economic growth and finally accelerating inflation.

The blame-game should stop forthwith

Hence, the ominous debt profile is the public enemy number one looming over Sri Lankans today. The two major political players who have shared the political power in the country since independence have been on a ‘blame game’ accusing each other for the critical state in the country.

The most commonly used debt-burden indicator is the amount of public debt falling on a single individual in the country, a figure derived by dividing the total public debt by the total number of people in the country. By quoting this number, they are in the habit of awarding a clean certificate to themselves, while accusing their political rivals.

However, if any political party is desirous of earning this clean certificate, there is a fundamental qualification which it should have acquired. That is, when that political party had been in power, the government budgets its finance ministers had presented should have been either balanced budgets or surplus budgets. If they had been balanced budgets, they do not add new debt to the debt profile. If they had been surplus budgets, they have indeed repaid some of the previous debt thereby contributing to shrinkage of the total debt.

The bold example by M.D.H. Jayawardena

In this respect, there is only one Finance Minister in the whole of the post-independence history who can claim that he has not added debt burden on the people. That was M.D.H. Jayawardena who held the Finance Portfolio during 1954 to 1956. In his budgets of 1954 and 1955, he had surplus budgets of 0.5% and 2.2% of GDP, respectively.

The macroeconomic achievements during this short period were for the better. The total public debt fell from 27% of GDP in 1953 to 21% by 1955. Government’s borrowings from the Central Bank and commercial banks on a net basis, that is, after setting off Government deposits from borrowings, declined from Rs. 455 million in 1953 to Rs. 186 million in 1955. The beneficial effects on inflation and economic growth were remarkable during this period. Inflation rate, measured in terms of the Colombo Consumers’ Price Index, fell from 1.6% in 1953 to a negative 0.5-0.6% in 1954 and 1955 and continued to be in the negative range even in 1956 before accelerating to 2.6% in 1957.

Economic growth accelerated from 2% in 1953 to 6% in 1955. In the subsequent four-year period, growth fell again on average to 1.6% per annum. Sri Lanka had a comfortable surplus in the balance of payments or BOP amounting to about $ 60 million in each of the two years. Since then, Sri Lanka’s BOP turned to be negative, depleting foreign reserves, putting pressure on the fixed exchange rate to be devalued by the Government and forcing the authorities to impose the most stringent import and exchange controls on the citizens. Thus, all Finance Ministers, except M.D.H. Jayawardena, are guilty of the present sad state of debt overhang in the country.

Proposing to settle debt by borrowing more

The leading candidates contesting the forthcoming Presidential Election of 2019 have expressed their anger at the overhanging debt problem in the country.

However, the solutions they have suggested pose two issues. One issue relates to the strategy of borrowing funds from a cheaper source and repaying the existing foreign debt. Such an approach can be applied only in the case of the maturing debt owed by the Government and not by the private sector borrowers. This is because the early repayment of the entire debt portfolio would require elaborate negotiations with creditors and, in most cases, a payment of a penalty.

Sri Lanka’s private sector also owes some $ 21 billion to diverse creditors and any early repayment arrangement has to be made by individual borrowers having negotiated with individual creditors. A President representing a country cannot do this. It is worthwhile to note that, with regard to the maturing debt, this approach suggested by some of the key presidential candidates is exactly similar to the debt recycling being done by Government debt authorities.

What is ignored by all the parties is that it does not take the country out of debt. It simply make the country more indebted trapping it in a bigger debt burden, since it now has to borrow money even for paying interest on the existing debt. Hence, this solution is similar to the proverbial saying in Sinhala ‘making the chair by dismantling the barn’.

Debt should be repaid via real sacrifices

The second issue arises from a misunderstanding that a country can get out of debt without making a real sacrifice. Though debt is denominated in money form, it is not money that is lent. A lender has to save a part of his real earnings to give out as a loan by sacrificing his current consumption in favour of consumption to be made in the future.

For instance, if I borrow one rupee, I do not simply borrow it in money form. The person who lent me that one rupee has to sacrifice his real consumption equal to one rupee. When that one rupee is transferred to me, I have the ability to command over a basket of real goods and services worth of one rupee. Hence, when I repay it and pay interest on it, I transfer to my creditor a basket of real goods and services worth of one rupee and the interest component applicable to it. Hence, debt repayments are not mere financial repayments but transfers of real goods and services to creditors by borrowers.

The political leaders appear to be of the belief that they can take a country out of debt simply by making only a financial transfer.

The weird story of an African country solving its debt problem

Apparently, this view that debt could be settled by mere financial transfers has arisen from a story that has gone viral in the social media about a country getting out of debt simply by using a hundred dollar bill paid as advance to a hotel clerk for occupying a room in that hotel. The story in question is as follows.

An American tourist comes to an anonymous African country where people are indebted to each other. When the American asks for a room in the only hotel in the country, the receptionist insists that he should pay an advance of $ 100. The tourist who hands a 100 dollar bill to the receptionist hangs around in the lobby until the room is ready for him.

The receptionist uses the 100 dollar bill to settle the hotel’s debt to the butcher; butcher to settle debt to his daughter’s tuition master, the tuition master to a gold smith, gold smith to a prostitute and so on. Finally, the prostitute comes to the hotel with the 100 dollar bill and pays the receptionist to buy a beer from the hotel. The tourist who is not satisfied about the quality of the room refuses to stay there and asks for the advance he has paid. The receptionist who now has the 100 dollar bill promptly returns the advance. But by that time, all the people in the country have now settled all their debt and are ready for a new beginning.

Suggestion that Central Bank should print money and repay Government debt

Having been enamoured by this story, a senior politician suggested to me that the Sri Lankan Government can settle all its domestic debt if the Central Bank prints Rs. 1 trillion and lends to the Government. After the Government has paid all its debt, the Central Bank can adopt a tight monetary policy and take that money back to prevent it from causing inflation.

I told him that the story has two defects. One is that it still has the issue of how the Government will repay its debt to the Central Bank. The other is its wrong assumption that debt can be settled permanently by the transfer of mere financial funds to creditors. That should come from sacrificing real resources in favour of the Government by way of taxes. That is why in the good olden days people paid taxes to kings in real goods. But, this is a painful affair and for a country ridden with mounting debt, there is no any other option available.

The way out is only by real sacrifices

Thus, the presidential hopefuls intent on resolving the country’s debt problem permanently should follow only one policy option. That is to run a surplus in the budget, as was done by M.D.H. Jayawardena in 1954 and 1955, and start repaying the existing debt. But, this will address only the domestic debt of the Government. About the foreign debt owed by both the Government and the private sector, the proper course is to strengthen the country’s foreign exchange earning capacity by promoting export of merchandise goods and services.

Any other measure done will simply be a temporary palliative that would worsen the country’s conditions in the long run.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)