Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Wednesday, 18 February 2026 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka stands at a defining moment in its economic recovery. Engagement with the International Monetary Fund has anchored a programme of fiscal consolidation, debt restructuring, and structural reform intended to restore macroeconomic stability. Considerable emphasis has rightly been placed on revenue mobilisation, expenditure discipline, and restructuring of major State-Owned Enterprises.

Sri Lanka stands at a defining moment in its economic recovery. Engagement with the International Monetary Fund has anchored a programme of fiscal consolidation, debt restructuring, and structural reform intended to restore macroeconomic stability. Considerable emphasis has rightly been placed on revenue mobilisation, expenditure discipline, and restructuring of major State-Owned Enterprises.

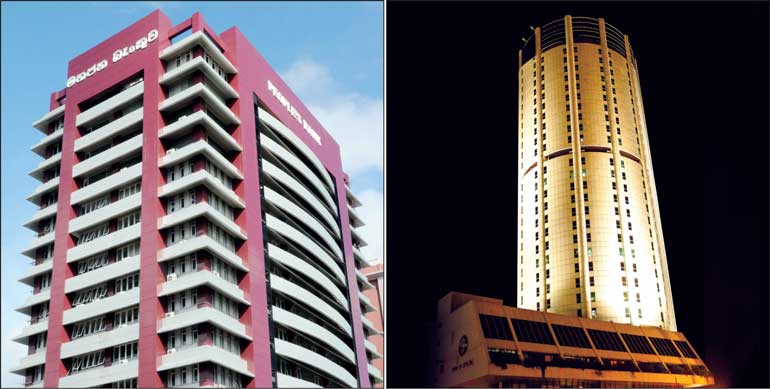

Yet one pillar of long-term stability demands equal — if not greater — attention: the strength, transparency, and governance of State-owned banks. These institutions are not peripheral actors within the financial system. They are systemic anchors. They hold a dominant share of public deposits, maintain significant exposure to Government securities, finance key State enterprises, and historically have served as instruments of national development policy. Their balance sheets are deeply intertwined with the sovereign’s own financial health.

It is therefore insufficient to assume that macro-stability at the fiscal level automatically ensures stability within the banking sector. Banking resilience must be independently safeguarded.

Lessons from institutional memory

Those associated with Sri Lanka’s banking landscape in the 1990s will recall a sobering episode. Institutions widely perceived as stable — presenting orderly accounts and operating under an appearance of normalcy — were suddenly declared insolvent. The announcement sent shockwaves through depositors, markets, and public confidence.

The crises did not emerge overnight. They matured gradually beneath structured presentations, delayed recognition of asset deterioration, and insufficient provisioning discipline. When liquidity tightened and external conditions shifted, the underlying fragilities surfaced abruptly.

The lesson remains timeless: financial distress often accumulates quietly before it becomes visible. This historical reference is not intended to suggest that similar outcomes are imminent today. Regulatory frameworks have evolved considerably. Capital adequacy standards, Basel compliance requirements, stress-testing methodologies, and supervisory mechanisms under the Central Bank are far more advanced than three decades ago.

However, sophistication of framework does not eliminate the need for vigilance. In some instances, modern accounting systems — while technically robust — can create layers of complexity that obscure early warning signals through restructuring classifications, deferred impairment recognition, and valuation assumptions that soften immediate impact. The purpose of recalling history is not alarm, but institutional memory.

Transparency in asset quality and provisioning

In a period of economic adjustment marked by debt restructuring, exchange rate volatility, and stress within borrowing sectors, asset quality transparency becomes paramount.

In a period of economic adjustment marked by debt restructuring, exchange rate volatility, and stress within borrowing sectors, asset quality transparency becomes paramount.

Restructured and rescheduled loans must be clearly distinguished from genuinely performing assets. Temporary deferment of repayment obligations, while sometimes necessary, cannot substitute for sustainable recovery capacity. Reclassification mechanisms should not mask underlying vulnerability.

Provisioning discipline remains the cornerstone of prudential banking. Under-provisioning — whether driven by optimism, competitive pressure, or reluctance to recognise impairment — merely shifts risk into the future. True stability requires conservative recognition of potential loss.

In addition, concentration risks — particularly large unsecured exposures or sectorally concentrated lending — warrant periodic independent review. In an economy emerging from crisis, diversified and prudently secured portfolios are essential safeguards.

These concerns are systemic considerations inherent in post-crisis environments.

Development mandate versus commercial drift

State-owned banks in Sri Lanka were historically conceived not merely as commercial entities, but as development catalysts. Agriculture, small and medium enterprises, infrastructure, regional industry, and long-term productive sectors benefited from structured financial support aligned with national policy objectives.

Over time, however, operational culture has increasingly mirrored purely commercial banking models. Financial discipline is indispensable; profitability and capital strength are non-negotiable. Yet an excessive tilt toward short-term balance sheet optics can dilute the broader developmental role for which public ownership exists.

Development banking does not imply concessional laxity. On the contrary, it demands disciplined, well-structured, risk-aware financing aligned with national economic strategy. When developmental mandates erode into routine commercial activity, public ownership risks becoming nominal rather than functional. The challenge is therefore balance — preserving commercial prudence while reaffirming developmental purpose.

Governance autonomy and strategic accountability

State-owned banks today operate under duly granted autonomy. Boards are constituted in accordance with prevailing governance frameworks, and Treasury representatives often serve as nominee directors reflecting the Government’s shareholding interest.

Autonomy in commercial decision-making is appropriate. However, autonomy without structured strategic accountability can gradually detach institutional direction from national economic priorities. A legitimate question arises: beyond shareholder representation, is there a sufficiently robust and formalised reporting mechanism linking State banks to the country’s senior financial leadership at a strategic level?

Are periodic high-level financial reviews conducted that go beyond routine profitability indicators to examine:

Alignment with national development priorities

Alignment with national development priorities

Sectoral credit distribution patterns

Sectoral credit distribution patterns

Exposure concentration risks

Exposure concentration risks

Sovereign exposure levels

Sovereign exposure levels

Long-term capital adequacy buffers

Long-term capital adequacy buffers

Implementation of corrective measures highlighted by oversight bodies

Implementation of corrective measures highlighted by oversight bodies

Effective oversight does not require political interference. It requires professional, non-political financial supervision insulated from partisan cycles but actively engaged in strategic direction.

If governance structures operate in silos — boards functioning independently, Treasury representation confined to shareholder formalities, and policy alignment assumed rather than examined — institutional drift becomes possible.

In an era of reform, governance design matters as much as capital ratios.

Oversight and institutional follow-through

Parliamentary oversight mechanisms such as the Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) have in recent years brought to light governance concerns, exposure irregularities, and procedural lapses within public institutions, including financial entities. Public exposure of weaknesses is valuable. Yet equally important is systematic follow-through.

Parliamentary oversight mechanisms such as the Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) have in recent years brought to light governance concerns, exposure irregularities, and procedural lapses within public institutions, including financial entities. Public exposure of weaknesses is valuable. Yet equally important is systematic follow-through.

Are corrective recommendations implemented in measurable timelines? Are periodic updates publicly disclosed?

Are structural governance adjustments institutionalised rather than episodically addressed? Transparency regarding implementation progress would significantly strengthen public confidence. Accountability is not complete at the moment of exposure; it is complete only when corrective architecture is demonstrably strengthened.

Lessons from risky strategic decisions

We have also witnessed episodes where financial ventures — including derivative exposures and hedging arrangements — resulted in significant State burdens when global conditions shifted unfavourably. Such experiences underline the risks associated with deviation from core prudential banking principles.

Financial “innovation” divorced from risk containment can become costly experimentation.

Institutional memory must serve as preventive wisdom. In a fragile macroeconomic environment, adherence to conservative risk frameworks is not a constraint and not infra dig — it is protection.

Reform must be structural, not cosmetic

Sri Lanka’s economic recovery cannot rely solely on fiscal consolidation metrics and quarterly stability indicators. Sustainable progress requires deep institutional reinforcement.

If fiscal discipline is pursued aggressively, financial sector discipline must advance with equal determination.

Stronger independent audit scrutiny, enhanced transparency of asset classification, conservative provisioning frameworks, structured public disclosure of corrective implementation, formalised high-level strategic financial review mechanisms, and reaffirmation of disciplined developmental banking would collectively signal seriousness of reform intent.

This is not a call for alarm. It is a call for pre-emptive strengthening.

Economic crises rarely arrive without warning. They mature in environments where early signals are muted, where governance gaps widen gradually, and where institutional oversight becomes procedural rather than substantive.

Sri Lanka has endured a severe economic contraction. Public trust, once shaken, requires deliberate rebuilding. The credibility of State-owned banks is integral to that trust.

The time to reinforce foundations is when stability appears intact — not when visible cracks compel reactive intervention. Reform, to be credible, must be structural rather than cosmetic; vigilant rather than complacent; developmental rather than transactional.

The country’s financial architecture must emerge from this reform era not merely stabilised, but strengthened in governance, transparency, purpose and accountability.

Sri Lanka cannot afford to relearn old lessons at new cost.