Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Thursday, 16 June 2022 00:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

To strengthen efforts of climate change adaptation and scale up support, countries around the world are envisioning a Global Goal on Adaptation

For the last two weeks, the nations of the world have come together in Bonn, Germany to discuss and negotiate a range of issues related to climate change. This includes the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, but also questions of adaptation, loss and damage, climate finance or capacity-building.

For the last two weeks, the nations of the world have come together in Bonn, Germany to discuss and negotiate a range of issues related to climate change. This includes the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, but also questions of adaptation, loss and damage, climate finance or capacity-building.

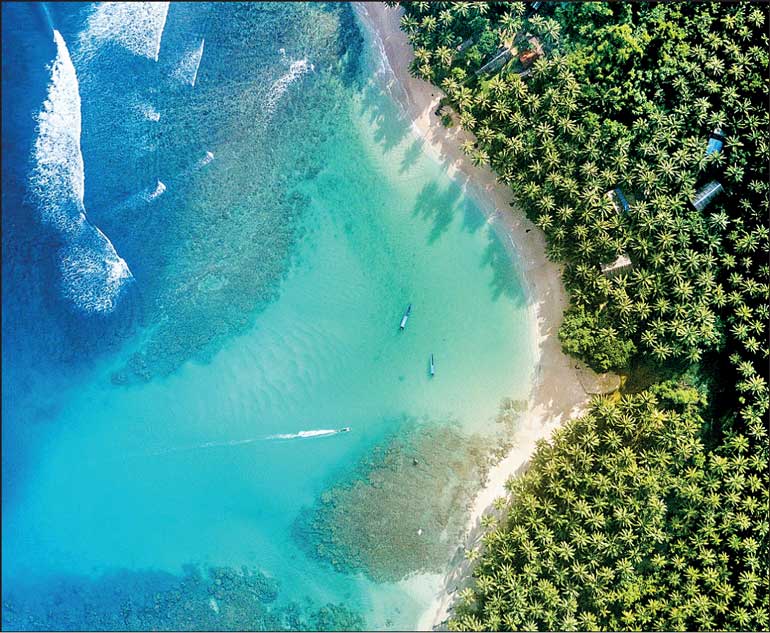

Particularly for vulnerable developing countries like Sri Lanka, it will not be enough to limit future warming, as they are already facing serious climate-related impacts. Economies, communities and ecosystems must build their resilience and adapt to the changing circumstances brought about by past and present temperature rise. To strengthen these adaptation efforts and scale up support, countries at the Bonn Climate Change Conference are therefore envisioning a “North Star” that can provide guidance and direction: the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA).

Adaptation, resilience and the purpose of a global goal

The Global Goal on Adaptation was established with the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change adopted in 2015. Article 7 of the Agreement outlines a global goal of “enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience, and reducing vulnerability to climate change” which is supposed to also contribute to sustainable development and connect with the overall temperature goal of the Agreement.

The Paris Agreement aims to keep global temperature rise to well below 2 degrees and ideally below 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. As highlighted by recent climate science reports, every fraction of a degree of warming can lead to significantly more devastating impacts and ambitious mitigation efforts are pivotal to keep planet Earth habitable. However, even a temperature rise of 1.5 degrees or less can lead to far-reaching climatic changes as well as losses and damages, many of which are already visible around the world.

To minimise—or even capitalise on—the climatic changes that cannot or have not been prevented by mitigation, adaptation actions are of paramount importance. The website of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) defines adaptation as “adjustments in ecological, social, or economic systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli and their effects or impacts [as well as] changes in processes, practices, and structures to moderate potential damages or to benefit from opportunities associated with climate change.”

Similarly, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) refers to adaptation as “the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects. In human systems, adaptation seeks to moderate or avoid harm or exploit beneficial opportunities. In some natural systems, human intervention may facilitate adjustment to expected climate and its effects.”

These two definitions already call attention to a fundamental challenge in developing a Global Goal on Adaptation. Adaptation comes in many shapes and forms and all of them are context-specific, highly dependent on local geographies, resources, capacities and socioeconomic, cultural, and policy environments. Finding a way to aggregate or synthesise such a multitude of different ideas and actions will be a difficult and complex process.

Working towards the Global Goal on Adaptation

At the end of 2021, countries came together in the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26) and decided on a pathway toward developing the Global Goal on Adaptation. This resulted in the establishment of the Glasgow-Sharm el-Sheikh work program, which started immediately after and will run throughout eight workshops until the end of 2023. The last two weeks, the first of these eight workshops have taken place and countries have had the chance to exchange views, priorities, and preferences on the GGA.

Key questions to answer include the following: How can we measure adaptation success and progress? What are metrics and indicators across different regions? How can countries report on their adaptation actions without facing additional burdens? What is the function of a global goal, how can it help countries to access finance and support? And finally, how will the GGA connect to the Global Stocktake in 2023, which is the first assessment of global progress towards the goals of the Paris Agreement—a survey of how far the world has come on mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage.

With adaptation being so context-specific, it is difficult to find a common language among almost 200 countries and different actors working on adaptation. The first GGA workshop provided a starting point, but there is much work left to be done after Bonn. For the rest of the year and throughout 2023, the remaining workshops will focus on different thematic aspects, with the next major climate conference (COP27) being convened in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, in November 2022. To operationalise a GGA that is fit for purpose, countries will have to decide on methodologies, sources of finance and support and mechanisms to bring together evidence, knowledge, policy processes, and a multitude of other considerations.

(The writer works as Director – Research and Knowledge Management at SLYCAN Trust, a non-profit think tank based in Sri Lanka. His work focuses on climate change, adaptation, resilience, ecosystem conservation, just transition, human mobility and a range of related issues. He holds a master’s degree in Education from the University of Cologne, Germany and is a regular writer to several international and local media outlets.)