Friday Mar 06, 2026

Friday Mar 06, 2026

Thursday, 25 May 2023 00:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

AKD’s two-camp theory is dangerously flawed. A political arena has three not two spaces: the two camps at the two opposing poles and the third space comprising the crucial intermediate strata which have to be won over or neutralised. These are not only socioeconomic strata. They are also political, ideological and public opinion strata. It is the camp that wins over the middle ground, swings the intermediate elements, that wins. Because every party has an organic mass-base, the only proven pathway to achieve that goal is the united front. Even with an auxiliary ‘front’ as avatar, no single party can do that. The camp that fails to establish alliances, partnerships, ultimately loses—as did the JVP in its two previous bids for state power

AKD’s two-camp theory is dangerously flawed. A political arena has three not two spaces: the two camps at the two opposing poles and the third space comprising the crucial intermediate strata which have to be won over or neutralised. These are not only socioeconomic strata. They are also political, ideological and public opinion strata. It is the camp that wins over the middle ground, swings the intermediate elements, that wins. Because every party has an organic mass-base, the only proven pathway to achieve that goal is the united front. Even with an auxiliary ‘front’ as avatar, no single party can do that. The camp that fails to establish alliances, partnerships, ultimately loses—as did the JVP in its two previous bids for state power

President Ranil Wickrem-esinghe’s on-going attempt (as reported in our Sunday sister-paper) in the face of TNA objections, to foist a puppet Interim Administration for the North and East, caricaturing ‘President’s Rule’ in India instead of holding long-overdue Provincial Council elections (as repeatedly urged by India), is a dark portent of complete closure of the political system.

President Ranil Wickrem-esinghe’s on-going attempt (as reported in our Sunday sister-paper) in the face of TNA objections, to foist a puppet Interim Administration for the North and East, caricaturing ‘President’s Rule’ in India instead of holding long-overdue Provincial Council elections (as repeatedly urged by India), is a dark portent of complete closure of the political system.

Wickremesinghe’s refusal to hold PC elections and attempt to set up an Interim Administration instead, makes nonsense of the chatter about early presidential elections. His acute election-phobia validates the conviction of JVP-NPP leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake and FSP leader Kumar Gunaratnam, that he displays no intention whatsoever of holding a Presidential election on schedule next year and every intention of doing otherwise.

Anura’s continuing rise

If President Wickremesinghe thought that indefinitely postponing the local authorities election would contain and roll-back Anura Kumara’s popularity, he was very wrong indeed. A democracy deficit only radicalises public opinion.

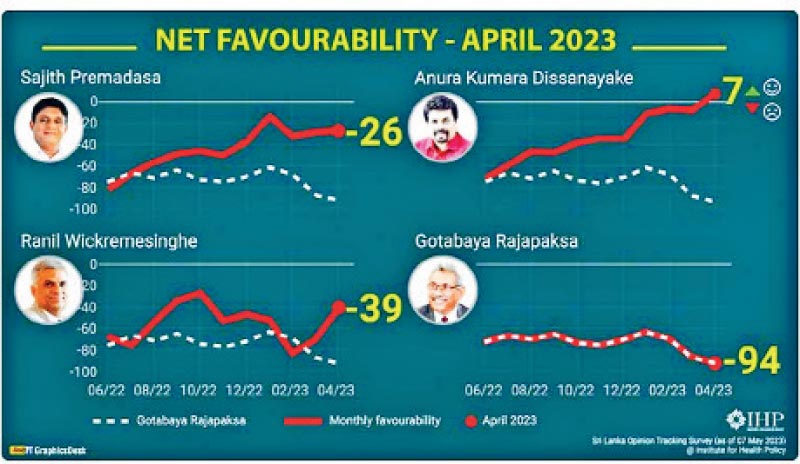

The Daily FT broke the story, its caption saying it all: AKD only major party leader with positive net favourability rating in April | Daily FT

Harvard-trained Dr. Ravi Ranan-Eliya’s tweet, with a link to the IHP News release, summarised its findings on ‘favourability’ as follows (the breakdown into bullet points is mine):

It is a reasonable assumption that these figures translate into voter preferences at a Presidential election, giving AKD the lead. It is also reasonable to assume that these figures would be an indicator, though inexactly, of parliamentary election preferences, with the NPP-JVP ahead.

None of this means that Sajith and the SJB, running 2nd, should unite with a Ranil/UNP combine running way behind.

It does mean that the SJB has to be much more dynamically social democratic and robustly Premadasa-populist, while formalising the FPC partnership and attracting the SLFP too.

|

Left Opposition leader

|

|

FSP’s Duminda Nagamuwa

|

|

Pubudu Jayagoda: Public policy expert

|

|

Nicos Poulantzas

|

Rajan Phillips’

Harini candidacy

The IHP/SLOTS empirical evidence undermines the suggestion by respected columnist and (ex-Samasamajist) leftist Rajan Phillips last Sunday. He opined, in an ever-so-slightly classist analysis, that:

“… Anura Kumara Dissanayake himself may have peaked to his full potential even before any election has been called. That is coincidental benefit for Ranil Wickremesinghe… He [AKD]…should be the JVP/NPP’s candidate for Prime Minister in a parliamentary election” … [while] “presenting Harini Amarasuriya as the JVP/NPP presidential candidate”. (Elections Season & JVP/SJB Options - Colombo Telegraph)

That’s a genuinely bad idea. The JVP’s cadre and constituency are unlikely to be galvanised to fight the ground-game by a candidate who is neither ‘organic’, nor a party leader of long-standing, nor yet a public personality with a national profile embracing the provinces/rural voters, at an election in which the stakes are the leadership of the country and which they hope to win. I had presented the idea of an AKD candidacy as far back as 21 April 2014 (Elections 2015: The Stakes - Colombo Telegraph) and had been critiqued by the international Trotskyist Left. The World Socialist Website ran a story titled ‘Sri Lankan ex-radical calls for a JVP presidential candidate’, dated 13 May 2014. An extract follows:

‘…In an article published last month, entitled “Elections 2015: The Stakes,” Jayatilleka…examines possible opposition candidates, but his conclusion is striking. “What is needed to prevent catastrophe is a Hassan Rouhani-type candidacy: a moderate patriot/nationalist i.e., liberal or progressive Sinhala Buddhist.” He insists that a leader from the right-wing UNP or another “common candidate” would be no match for Rajapakse.

…Casting around for a Sri Lankan Rouhani to galvanise the opposition, Jayatilleka anoints the JVP leader: “The country would be better served by rallying round an out-of-the box presidential candidacy from the Left Opposition: Anura Kumara Dissanayake. I regard him as a far more serious moral, ethical and ideological challenge to the Rajapakse ‘Raj,’” he declares.

“Renewal of the JVP through its new young leader [Dissanayake] brings to mind the electoral renaissance of ex-revolutionary groups in Latin America,” Jayatilleka wrote. “Given the urgency of the Sri Lankan crisis, I have no hesitation in saying … society may—and should—shift a few steps leftward, to a JVP-centric broad Oppositional project at both Presidential and parliamentary elections … along the lines of the successful Latin American populist-democratic left.”‘ (Sri Lankan ex-radical calls for a JVP presidential candidate - World Socialist Web Site (wsws.org)

The problem is not with AKD as presidential candidate. That way, at the least he’ll be the Opposition leader, poised to give Sri Lanka a long-deserved left leadership after a shaky one-term interregnum. The real problem is with AKD’s binary ‘two-camp’ theory.

Left looking good

Last week, exceptionally, I watched two long programs in Sinhala all the way through. On Rupavahini’s ‘Karata Kara’, the UNP speaker Dr. Keerthi Manchanayaka blithely admitted that profitable state enterprises would be sold together with loss-making ones because the real need was to break the power of the trade unions linked to political parties, including the Jathika Sevaka Sangamaya of the UNP itself. The logic of the UNP’s ‘total privatisation’ policy was not economic but extra-economic: it was a war against the trade union movement, and could be won only by wiping out its base in the state sector through the elimination of the state sector itself.

It wasn’t Dr. Manchanayaka’s ‘Goldfinger’-vibe that drew me into the show and kept me watching till the end. It was the substantive opening statement by the radical left FSP’s young trade union leader Duminda Nagamuwa, who combined mediagenic looks, persuasively knowledgeable argumentation, sincere and passionate delivery, and an unruffled, amused coolness in the face of his UNP opponent’s arrogant articulation of class war. (Karata Kara | 2023-05-15 | Rupavahini - YouTube)

The second program I watched—second in sequence, not significance—was an interview on Siyatha TV’s ‘Turning Point’ with Anura Kumara Dissanayake. My big takeaway was how impressively fast he was growing—reading the socioeconomic trends on the ground, fine-tuning his message and resonating with the public. He was passionate when talking in detail about the human suffering caused by crisis and the regime’s policies, credible when indicting those responsible, and persuasive in sketching an inside-out, bottom-up reformist solution. Watching him, I thought “He’s growing into it; he’s getting there…if he keeps improving at this pace, this guy can make it.” But will he?

AKD’s ‘two camps’

Anura explicitly and emphatically posits in his public speeches and Siyatha interview, a ‘two-camp theory’: It’s us versus them, they are ganging up against us, or are all criticising us and will eventually gang-up against us. Anyway, we don’t want to be tainted by association with them.

Perhaps I can best summarise his argument by paraphrasing a wisecrack by Philip Marlow answering a bartender in a Raymond Chandler novel: “In the first place we don’t like them, in the second place they don’t like us, and in the third place, we don’t like them in the first place”.

Anura’s diagnosis is that Ranil Wickremesinghe will not willingly hold the Presidential election constitutionally fixed for next year and will try to do as he has done to the local authorities election. If so, his prescription logically cannot be a ‘two camp theory’ based on a demarcation between those who are against the IMF program and those who are not, nor between those who are responsible for the crisis by being power-wielders in the past, and those who are not. Instead, AKD would have to recognise the most pressingly relevant ‘two camps’ as (a) those who stand against any postponement and are willing to fight for the securing of a Presidential election next year and (b) those who are not.

Anura’s current, narrowly binary demarcation is excusable only if he is certain of a Presidential election on schedule. His problem is that he transposes a ‘two camp’ model suitable to a normal democratic context, onto a very different context which, by his own account is anything but normal: an unelected ruler intent on entrenching himself without elections. The ‘two camps’ that would be necessary in the face of a credible threat to elections would be very different from the two camps that would be permissible in a context of assured open democratic electoral competition on schedule.

The ‘two camp’ theory assumes that it would take only the JVP-NPP to lead the entire mass movement necessary to wrest an election from Ranil or displace him. This implies it is unnecessary to bring together all parties or as many as possible to do this.

In the AKD’s model, the enemy camp is defined in the most expansively elastic terms, and the people’s camp in the most constrictive. The enemy camp doesn’t have only Ranil and the SLPP parliamentarians, but everyone in the Opposition, i.e., everything and the kitchen sink. Politically, the people’s camp has only the JVP-NPP, which it is presumed everyone has rallied around or inevitably will.

AKD’s ‘two camp’ theory doesn’t isolate the enemy. Instead, it transfers the intermediate or vacillating political forces into the camp of the enemy, thereby swelling the latter’s support-base and/or buffer.

Mao posited as the central strategic question, “Who are our friends, who are our enemies?” In Anura’s two-camp theory the JVP-NPP has no political friends and needs none, because it has the totality of the people (‘samastha janathaava’)’ with it.

The JVP-NPP’s two-camp model eliminates space for political partnerships, alliances, united fronts and blocs. Politically, it only enables the JVP (with AKD as leader) to partner/ally/unite with the NPP (with AKD as leader). ‘Unite the many, defeat the few’, taught Mao. ‘Unite the many, defeat the almost-as-many’ teaches Anura.

The ‘two camp’ theory operates as a horizontal construct: us vs. them. Marxist philosophy however, hierarchises contradictions, identifying the principal contradiction and distinguishing it from secondary contradictions. Without this methodology no identification is possible of the main enemy, and no distinction can be drawn between ‘antagonistic contradictions’, i.e., those between oneself and the enemy, and ‘non-antagonistic contradictions’, i.e., those between oneself and friends/potential friends.

AKD’s two-camp theory is dangerously flawed. A political arena has three not two spaces: the two camps at the two opposing poles and the third space comprising the crucial intermediate strata which have to be won over or neutralised. These are not only socioeconomic strata. They are also political, ideological and public opinion strata.

It is the camp that wins over the middle ground, swings the intermediate elements, that wins. Because every party has an organic mass-base, the only proven pathway to achieve that goal is the united front. Even with an auxiliary ‘front’ as avatar, no single party can do that. The camp that fails to establish alliances, partnerships, ultimately loses—as did the JVP in its two previous bids for state power.

The Latin American Left learned two lessons from the bloodbath in Chile. Firstly, that however pacifistically ‘vegan’ the Left is, that won’t prevent the predatory Right from bloodily savaging you. Secondly, that having an arithmetical majority in support of you as Salvador Allende did, won’t enable you to survive. You need to make openings in all directions that enable you to win over a great majority. This realization led the Latin American Left to combine Guevara with Gramsci, placing greater emphasis on the latter. The success of the contemporary Latin American Left is attributable to its absorption and application of Gramscianism, which included the incorporation of Populism (as best theorized by Ernesto Laclau).

In Left Populism, the enemy camp is defined narrowly and is easy to isolate: the super-rich, the elite, “the 1%”. The ‘national-popular’ camp is expansive and inclusionary: “the 99%”. By contrast, the JVP-NPP’s perspective assumes that the 30%-40% that Sajith’s SJB has is negligible, or will evaporate, or that its shift to the Ranil camp would be an affordable risk which need not be pre-emptively neutralized through ‘united front’ or ‘united action’ tactics. Latin American Left Populism would never make that strategic blunder.

If Anura Dissanayake holds fast to his ‘two-camps construct’, even if he wins the presidency next year—which is perfectly possible, given the statistical trends—Sri Lanka would remain divided into ‘two camps’ and the JVP’s policy in government would target one camp to the benefit of the other. This is a formula for a zero-sum game, a recipe for permanent polarization and internal Cold War at the least, or civil war and coups at the worst. Given great power and big power competition in the region, this scenario would be an invitation for economic blockade and external intervention.

The key link

AKD and the JVP-NPP should recall the fate of the LSSP in March 1960. It flaunted its hammer-and-sickle with the digit ‘4’ denoting the Trotskyist Fourth International, spurned a united left front with the Communists and the MEP, and exultantly expected Dr. NM Perera to lead the party to victory in the General Election and assume the country’s leadership as PM. He couldn’t, didn’t. Had the three-party United Left Front of 1963 been formed in 1960, he might have.

On the Janaka Ratnayake controversy, the recent spike of ethno-regional and ethno-religious chauvinisms and most other topics, the most rational perspective is from Pubudu Jayagoda, the FSP’s Educational Secretary and easily the most lucid public policy analyst/debater on TV. But why aren’t Pubudu Jayagoda and Duminda Nagamuwa on a united Left platform with AKD?

Lenin stressed the need to ‘grasp the key link’. The key link today is not the question ‘who will win the presidential election next year?’ but ‘who can and will secure a presidential election next year, and how?’.

The JVP-NPP should unite at this stage/phase with anybody who will commit to actively fight for the holding of the presidential election on schedule and against any attempt to delay it. Then, everyone can go their own way and fight each other in the electoral arena.

Nicos Poulantzas, the finest Marxist political theorist since Gramsci, identified in his last works a fatal flaw of the left: the tendency towards “monopartisme”. He emphasized “pluripartisme” instead, as condition of success of any strategy of transition. Latin America’s Left succeeded politically in two continental cycles (Pink Tides 1.0 and 2.0) over a quarter-century, through a pluri-party strategy (pioneered and permanently practiced by Uruguay’s MLN-Tupamaros since 1971).

The JVP’s thinking is not (yet) “a strategic-theoretical approach” as Prof. Bob Jessop spotlighted in his volume on Poulantzas. Therefore, Anura and the JVP-NPP err when answering the primary question of political praxis, immortalised by Lenin: ‘What Is to Be Done?’