Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Friday, 17 October 2025 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Every morning, I watch Kandy wake up — and cough. The horns, the fumes, the endless line of vehicles crawling through our small city. As someone who has lived here all my life, I no longer remember what clean air smells like. I’ve sat countless times behind a bus blocking an entire lane, waiting while it collects passengers in the middle of the road, only to be rewarded with a thick black cloud of exhaust when it finally moves.

Every morning, I watch Kandy wake up — and cough. The horns, the fumes, the endless line of vehicles crawling through our small city. As someone who has lived here all my life, I no longer remember what clean air smells like. I’ve sat countless times behind a bus blocking an entire lane, waiting while it collects passengers in the middle of the road, only to be rewarded with a thick black cloud of exhaust when it finally moves.

Kandy is beautiful. But beneath that beauty, it’s suffocating — literally.

Sri Lanka’s air pollution problem — Ground zero: Kandy

My field survey of 100 people showed what we all already know: 95% believe that vehicle emissions are the main cause of Kandy’s air pollution. More than half said the problem is serious; nearly one-third said it’s extremely severe. Over 60% said they suffer from breathing problems that they link directly to the air they breathe here.

That’s not surprising. The narrow roads of our hill city were never built for the 100,000+ vehicles that now flood in every day. According to Prof. Ileperuma, who has studied air quality in Kandy for decades, our city’s air is often worse than Colombo’s — trapped by the surrounding mountains and poisoned by rising vehicle numbers and daily congestion.

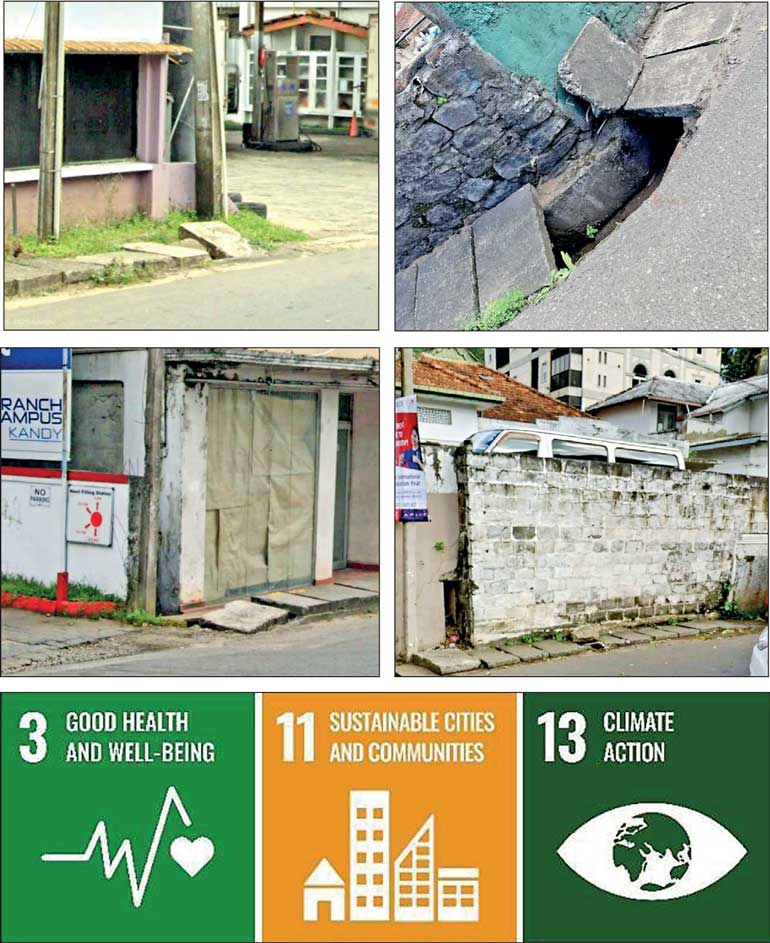

And it’s not just theory. During my observations, for the research and just by living here and going to school here, I saw broken pavements near major schools, forcing students to walk on the road. I, too, have been one of them. I remember having to walk along the road to avoid falling into pits nearly five feet deep, where concrete slabs had collapsed over open drains. I became one more body clogging traffic because the sidewalk — meant for me — was impassable.

The law is there — but who’s enforcing it?

Sri Lanka is not without laws. The National Environmental Act No. 47 of 1980 gives the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) the power to control pollution and advise the central government and local authorities. Under sections 10 and 12, the CEA can investigate environmental harm and take corrective action. Vehicle emission standards — in force since 2003 — make it illegal for vehicles to operate beyond permitted emission levels.

And yet, what do we see? Buses and lorries belching smoke every day, unchecked. Emission tests that exist on paper, but not in practice. A 2017 National Audit Office report confirmed what citizens have long known: vehicle exhaust is the major contributor to air pollution in cities, and enforcement is grossly inadequate. Though that’s there, I still get a mouthful of soot from the Mahakanda/Delthota buses that pass my University in little to no traffic.

The Sri Lankan Constitution itself, under Article 27(14), commits the State to “protect, preserve and improve the environment for the benefit of the community.” Under Article 28(f), we, the citizens, have a duty to protect nature and conserve its riches. But how are we to protect the environment when the very institutions meant to uphold these duties turn a blind eye?

Our international commitments — and national failures

Sri Lanka is a signatory to major international environmental instruments — including the Stockholm Declaration (1972), the Rio Declaration (1992), and the Paris Agreement (2015) — each reaffirming the right to a healthy environment. At the United Nations, we pledged to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Three of them directly apply to this crisis:

SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) — Target 3.9.1 aims to reduce deaths and illnesses from air pollution.

SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) — Target 11.6.2 calls for lowering the average levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in cities.

SDG 13 (Climate Action) – This goal urges countries to take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. Vehicle emissions are not only a local air-quality problem

Yet here in Kandy, PM2.5 levels on some mornings are three times the World Health Organization guideline. We are failing both our people and our promises.

What my research found

Through desk research, a field survey, personal observations, and an interview with Prof. Ileperuma, I identified recurring patterns:

Buses and lorries are the most polluting vehicles. (In the recent past it was the two-stroke engines of tuks and bikes)

Poor planning and lack of enforcement keep congestion chronic. The 6.4 km from Peradeniya to Kandy which only takes 10 minutes or less to travel by car at night takes more than 30 minutes during the day. Buses during rush hour traffic take well over an hour to go the same distance. As stated in the Project for Formulation of Greater Kandy Urban Plan, future demographic projections indicate a preposterous 72 minutes to travel the 4.5km distance from Gatambe to Kandy.

Broken infrastructure — sidewalks, parking, drainage, the rusty air-bridges that look like a standing tetanus shot that discourages pedestrians from using them— forces pedestrians into danger.

Weak public transport design: long-distance buses still start and end inside the city, instead of in outer terminals like Peradeniya, Katugastota, or Thannekumbura.

Through-traffic unnecessarily passes through the city instead of using bypass routes.

Although road widening projects are underway, the poorly managed construction process has actually worsened traffic congestion — with large sections of both roads from Peradeniya to Kandy being closed off simultaneously, and piles of excavated soil and rock left along the roadside further obstructing traffic flow.

The result? A cocktail of health hazards, lost productivity, and frustrated citizens. One respondent put it perfectly:

“Every day, I lose an hour in traffic. Every breath smells like diesel.”

The impacts: What’s at stake

The impacts go far beyond inconvenience. Pollution from vehicle emissions causes respiratory diseases, asthma, heart disease, and even strokes, as Prof. Ileperuma pointed out. He also stated that young school children in Kandy have increasing levels of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is a common lung disease seen in chronic smokers. Studies show that 97% of commuters believe traffic congestion seriously affects their productivity.

We’re losing time, health, and money — all because of inaction. Children inhale poisonous air on their way to school. Pedestrians risk their lives because of broken sidewalks. Businesses lose hours in gridlock. This is not just bad management — it’s an environmental injustice.

So what can we do?

We don’t need another report or committee. We need action.

Here’s what can and must be done:

Immediate steps

Repair broken sidewalks, especially near schools — before a child falls into a trench or is hit by a bus.

Crack down on visible smoke emitters — fine and blacklist buses and lorries (and everything else) that flout emission standards.

Ban long-distance buses from entering the city — start and end them at outer terminals.

Set up a hotline or mobile app for the public to report air pollution or road obstructions (over 40% of my survey respondents said they’d report if they knew how).

Medium to long-term solutions

Implement the Kandy Multimodal Transport Terminal and encourage rail or rail-bus travel (the rail-bus existed for a short period and had much potential but was aborted).

Create satellite towns in Peradeniya, Katugastota, and Thannekumbura to decongest the core.

Electrify public transport and enforce stricter inspection regimes. (But this requires adequate charging stations. One of the two easily accessed charging stations in the Peradeniya-Kandy area is powered by a generator that uses fossil fuels to operate)

Introduce parking management and one-way systems to improve traffic flow (the one-way system was introduced a decade or so back but was also snorted within a few days without expert consultation).

A final word — before we all suffocate

I’ve grown up in Kandy. I’ve seen it transform from a serene hill city into a suffocating traffic maze. Every day that passes without meaningful change is another day we poison our lungs and our future.

The right to breathe clean air isn’t a luxury — it’s a constitutional right. It’s a human right. And it’s time we demanded it.

The Central Environmental Authority, the Kandy Municipal Council, the Police, and every Government body involved must step up — not with words, but with visible, measurable action.

Because if we keep waiting, there’ll come a day when we’ll all look out over this beautiful city, see the mist, and wonder: “Is that the mist Kandy is famous for, or just the smog that we’ve normalised.”

(The writer is a year undergraduate student at the Department of Law, University of Peradeniya.)