Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Monday, 24 November 2025 00:13 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

As the country now attempts a deeper policy reset, we must confront an uncomfortable but crucial question: Should public funds continue to subsidise the act of farming, or should they reward the results?

As the country now attempts a deeper policy reset, we must confront an uncomfortable but crucial question: Should public funds continue to subsidise the act of farming, or should they reward the results?

Farming is a business, and policy must recognise it as one. Sri Lanka’s push for systemic reform presents a rare opportunity to correct long-standing distortions. A digital, output-based incentive system can strengthen food security, honor taxpayers, and transform rural livelihoods from merely “surviving” to truly “thriving”

For decades, Sri Lankan agriculture has been shaped by a culture of expectation. Successive governments have conditioned farmers to wait for handouts—especially fertiliser subsidies—before a single seed is planted. While politically irresistible, this model has bred dependency, distorted markets, and ultimately failed to lift national productivity.

For decades, Sri Lankan agriculture has been shaped by a culture of expectation. Successive governments have conditioned farmers to wait for handouts—especially fertiliser subsidies—before a single seed is planted. While politically irresistible, this model has bred dependency, distorted markets, and ultimately failed to lift national productivity.

As the country now attempts a deeper policy reset, we must confront an uncomfortable but crucial question: Should public funds continue to subsidise the act of farming, or should they reward the results?

The answer points squarely toward a shift to Output-Based Aid—a system where incentives are tied to verified production, not inputs, and enabled by robust digital infrastructure.

The “Break-Even” trap

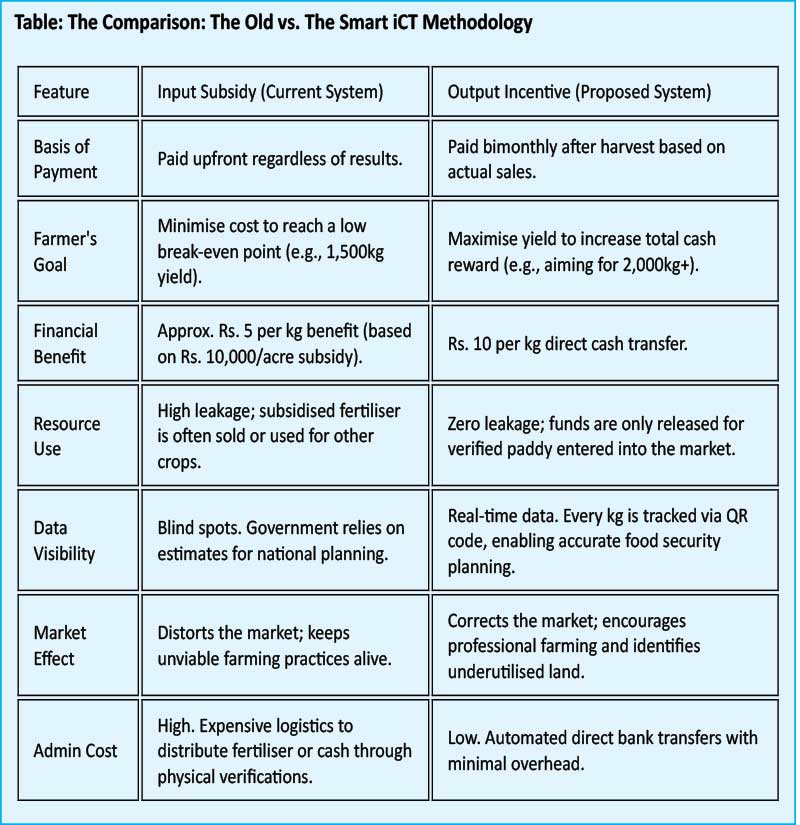

Input subsidies such as cheap fertiliser artificially suppress the real cost of production. This creates a harmful economic illusion: a lower break-even point that encourages farmers to “settle” rather than maximise yield. For instance, a paddy farmer enjoying subsidised fertiliser might meet their profit target at 1,800 kg per acre. Without the subsidy cushion, they would push toward the land’s true potential—around 2,000 kg.

This model breeds complacency rather than excellence. And it leaks public funds. Fertiliser diverted to black markets or non-food crops is a widely acknowledged problem. Some defend subsidies by arguing that not all production systems are equal. They are right—and that’s precisely why subsidies should help farmers transition from unviable crops to more profitable ones, not enshrine outdated systems. History offers a perfect example: when coffee failed, the British didn’t subsidise its survival—they backed the shift to tea.

The solution: A digital output-based incentive

Sri Lanka needs a system that pays for performance, not expectations. The proposal is straightforward: stop providing cheap fertiliser upfront and instead reward farmers based on the actual quantity of paddy they sell.

How it works?

The Backbone: A National ICT Platform tracks paddy production through a QR code system used by all registered buyers (much like the fertiliser pass for tea).

The Transaction: When a farmer sells paddy, the buyer scans the farmer’s QR code. Weight data from IoT-enabled digital scales automatically transfers to the national ICT system.

The Reward: For the Farmer: A direct cash incentive—for example, Rs. 10 per kg—is deposited into their bank account, in addition to the annually determined guaranteed price. Whereas today’s typical Rs. 10,000-per-acre fertiliser subsidy works out to roughly Rs. 5 per kg. A shift to Rs. 10 per kg in output incentives doubles the support for farmers who genuinely produce. Efficient farmers thrive. Inefficient ones are nudged—naturally—either to improve or to exit. For the Buyer: A small handling fee (e.g., Rs. 1 per kg) is paid to the government only if the digital weighing is not been used, encouraging accurate data though automated system entry and supporting field monitoring efforts.

The triple-win advantage

For farmers — The Producers: This is the most farmer-friendly system available. It replaces the stigma of handouts with dignified, performance-based earnings. Farmers who practice Integrated Plant Nutrition Systems (IPNS), manage soil health, and adopt modern methods will see their incomes climb. Productivity leads to farming profitable again.

For the Government — The Planner: Real-time digital data gives the state unprecedented visibility over national food stocks, land use, and production trends. Policymakers can make smart import decisions and detect underutilised land. If a registered paddy plot shows no sales (no QR activity) over time, it signals neglect. The government can then intervene to lease that land to more productive cultivators. No more leaving fertile land idle.

For the economy — Taxpayer money gets released only when food/rice is actually produced. Corruption, leakages, and the bloated logistics of fertiliser distribution shrink dramatically. Fiscal justice is finally built into agricultural support.

Overcoming implementation hurdles: Technology makes the shift practical, even inevitable.

Verification: IoT-enabled digital scales upload weight data directly. Manual certification by Agrarian Officers can function as temporary backup.

Digital literacy: If citizens adapted to the QR Fuel Pass under crisis conditions, they can adapt to a QR Fertiliser Pass for their own economic benefit.

Resistance: Some will resist—not because the system is flawed, but because inefficiency is profitable for them. The narrative must stay clear: this is not a cut; it is a smarter, fairer, more lucrative system for productive farmers.

Farming is a business, and policy must recognise it as one. Sri Lanka’s push for systemic reform presents a rare opportunity to correct long-standing distortions. A digital, output-based incentive system can strengthen food security, honor taxpayers, and transform rural livelihoods from merely “surviving” to truly “thriving”.

(The author is a Digital Agriculture Strategy Expert, a former top agriculture and policy specialist for the Sri Lankan and US governments, is currently leading a number of agriculture sector policy and digitalization initiatives locally and internationally. His considerable experience combines policy formulation and the use of digital tools to improve efficiency and sustainability in the agricultural sector.)