Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Tuesday, 26 April 2016 00:03 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The need for inclusive education for children with special needs

Children with disabilities or special needs often experience widespread violations of their rights. The World Report on Disability  estimates one billion people in the world are living with disabilities, of which 93 million children aged 0-14 years’ experience moderate or severe disabilities while 13 million children experience severe disabilities.

estimates one billion people in the world are living with disabilities, of which 93 million children aged 0-14 years’ experience moderate or severe disabilities while 13 million children experience severe disabilities.

Merely 10% of all handicapped children begin school yet, many drop out due to unpleasant experiences, and only 5% of children with disabilities worldwide complete their primary education. Inclusive education therefore recognises every child’s fundamental right to learn. It provides equal opportunities to all children and attempt to alter school culture, policies and practices to accommodate differences in learning and physical abilities of children.

Reliable and comparable disability data are under reported in most countries including Sri Lanka. According to UNICEF South and East Asian Regional Report, absence of information on handicapped children is the most significant factor contributing to the invisible status, which often leads to the exclusion of these children from education. Limitations of census and general household surveys to capture household disabilities; absence of civil registries in most low and middle income countries; underreporting due to the stigmatisation attached; unavailability of disability assessment and health screening to identify child disabilities and impairments, all underlie this ambiguity.

This article takes a look at the status of child disabilities in Sri Lanka, explores barriers to realising inclusive education and proposes policy recommendations to integrate them into mainstream economy.

Status of child disabilities in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s attention to provide education to children with special needs dates back to early 1970s when the Education Ministry initiated increasing opportunities for differently abled children through integration. More recently, emphasis has been placed on inclusive education with developments in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Although differently abled students are presently allowed to receive education in Government schools, either through inclusion in mainstream classrooms or special education units, due to choice or otherwise, these students attend special needs schools conducted by NGOs and the private sector.

According to the Census of Population and Housing 2012, within the age of 5-19 years, 53% of males and 47% of females are mentally and physically disabled children. Visibility impairments are the most common disabilities seen in both gender groups. Most functional disabilities are seen in the estate sector (9.3%) followed by 8.9% and 7.2% in the rural and urban sectors, respectively.

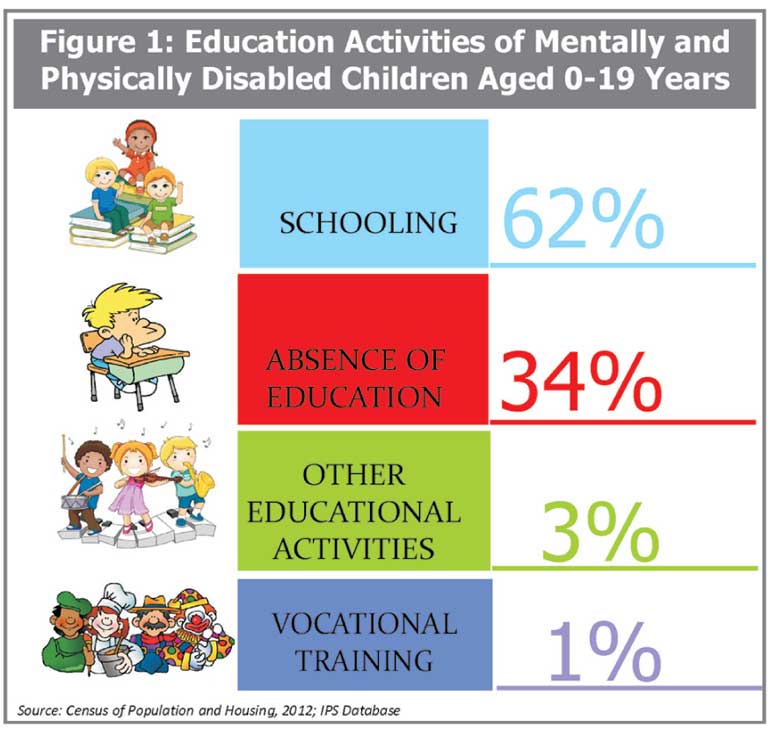

According to Figure 1, there are 88,740 mentally and physically handicapped children between the ages of 5 -19 years, of which 62% are receiving education through mainstream schooling, and 34% have not received any form of education. . These statistics indicate that the severely handicapped children with multiple and intellectual disabilities abstain from attending schools. This is because public and private provision of education lacks expertise and capacity to deal with such children.

Barriers to learning for disabled children

Societal attitudes: Perceptions and attitudes towards different types of disability vary among different stakeholders. A recent UNICEF study found that while handicapped children prefer to receive an education in regular classrooms, they fear reactions of peers towards their capabilities. Similarly, parents have signalled mixed opinions towards their support of special education, while teachers reveal mixed opinions towards including children with disabilities in regular classrooms. Concerns for supporting inclusion include lack of preparedness of schools, inadequate skills training, and time for planning and commitment. Many professionals are sceptical of the idea of inclusion, and prefer to provide education separately from the regular classroom.

Lack of access to basic services: Proper services and facilities that are key for such children to participate in the learning process do not exist in the country, restricting their access to education. Differently abled students are unable to reach educational institutions due to under-developed transport networks and distant learning centres. While such barriers affect all students in poorly serviced communities, particular groups of learners in wheelchairs for example, are more severely affected by these barriers. This hampers their education and is thus totally excluded from the education system.

Inflexible curriculum: Educators often through inadequate training fail to meet the needs of some of diverse learners. A study by Hettiarachchi et.al (2014) found that most teachers lack awareness and specific knowledge on inclusive methodologies to support children with special educational needs, which disempowers them from supporting children with special needs in their classroom. One off seminars and workshops are insufficient and professional development opportunities in an on-going basis are urgently needed.

A study by Abeywickrama et.al (2013) found the strong need for more material or equipment essential for the learner’s education, functional independence and interaction with others in the learning environment. Low cost assistive devices such as large print books, Braille text books and talking books are unavailable in many public institutions. Although poor economic status of the country contribute to this, a lack of exposure to information and knowledge in adopting classroom practices may be equally responsible. Furthermore, learning breakdown also occur through mechanisms used to assess learning outcomes.

Assessment processes are often found to be inflexible and designed to only assess the extent of information that can be memorised rather than the learner’s understanding of the concepts. Some due to their intellectual setback are then compelled to repeat aspects of the curriculum, which compel them to remain in levels where the age gap between the learner and peers are significant.

What can be done?

Overcoming myths of disability: Parents of children with disabilities are psychologically, emotionally and socially unprepared. They tend to feel isolated, frustrated and guilty. Parents, like wider society, may be ignorant about the causes of disability. Thus, it is vital to create proper awareness on early identification and intervention support, medical and therapeutic services, and early childhood education and schooling. Deliberating with other parents has proved valuable in helping them to gain new perspectives. Families need to be given factual information about the causes of disabilities and how the child can be helped. Seeing examples of children with disabilities involved in everyday activities has proved effective.

Providing in-service teacher training: Continuous professional development opportunities for educators handling disabled learners would help overcome obstacles entailed in inclusive education. In-service training programmes coupled with multiple components of professional development that include training, implementation guides, and classroom materials, instructional coaching, and performance feedback for teachers are vital. Workshops to equip teachers with practical skills on instruction and on alternative forms of evaluation, classroom management, and on how to adapt the curriculum will certainly assist in changing behaviours and perceptions of educators.

Use of information and communications technology: The use of technology for differently abled students has tremendous potential in alleviating particular problems associated with specific disabilities. Distance learning should be made accessible to allow students with disabilities to continue living at home while studying, share documents, exchange ideas and make presentations. Technology can also assist students with intellectual visual impaired disabilities, to follow educational courses via digital and audio libraries, access material, content and resources via the internet.

A close consideration of these strategies will certainly help secure a future for Sri Lanka’s children with special needs and combat certain limitations in promoting inclusive education.

(Yolanthika Ellepola is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To view the article online and comment, visit the IPS blog ‘Talking Economics’ – www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics.)